(Originally posted November 10, 2010. This got lost in the migration from TypePad to WordPress, recovered and reposted for the archives here thanks to the Internet Archive Wayback Machine.)

Tribulation Force, pp. 281-289

Nicolae Carpathia is supposed to be The Antichrist, which is a pretty big deal in premillennial dispensationalist mythology. That makes him the first horseman of the Apocalypse, the Beast, the epitome and embodiment of pure evil. He’s supposed to be superlative and historic — the most evil powerful man and the most powerful evil man of all time.

So far, though, it’s hard to take him seriously. He’s bumblingly through the first stages of his master plan, getting himself hopelessly bogged down in details that seem less evil than simply arbitrary and weird.

For example, Nicolae plans to rebuild the Temple in Jerusalem. That might be considered evil if he were doing it just to desecrate the Islamic holy site currently sitting there in an effort to start a deadly war, but instead he’s carefully negotiated an amicable (if ridiculously implausible) solution to this age-old conflict. But I guess we’re still supposed to regard the rebuilding of the Temple as evil because, well, Herod did the same thing, and Herod was evil. All that does, though, is invite a comparison between Herod’s cruelty and tyranny and Nicolae’s, and frankly Nicolae just doesn’t seem like he’s in Herod’s league.

Herod, remember, had that whole slaughter-of-the-innocents thing, while the only people Nicolae has killed so far were a journalistic rival of Buck’s and a couple of outright villains. Stonagal and Todd-Cothran ought to have been arrested rather than murdered in cold blood but, still, killing them seems less the work of Satan incarnate than of Charles Bronson in Death Wish incarnate. To be fair, of course, Nicolae couldn’t have slaughtered every infant in Bethlehem even if he’d wanted to, since God beat him to it by wiping out every infant and child on earth, but one would expect some kind of mass-slaughter from the Beast from Hell. It doesn’t say much about Nicolae as an evil tyrant that he rates below a guy like Herod who probably doesn’t even rank in the Top 10 of cruel tyrants from his own century, let alone all time.

Or consider Nicolae’s grand scheme of relocating the United Nations headquarters to an as-yet-unbuilt city in the Iraqi desert. That’s capricious and foolish, but not so much evil as just terribly wasteful and inconvenient. Naming this new city “New Babylon” would seem like a clear signal of evil intent — why else would he choose a name synonymous with oppression? But no one seems to take this name seriously. Even the Rastafarians are apparently on board in support of “New Babylon” — seeming to put all the emphasis on the “new” and very little on the “Babylon.” Nicolae doesn’t seem like he’s in Nebuchadnezzar’s league either.

It’s hard for me to think of any cruel tyrant from history who doesn’t seem far worse than this supposed apotheosis of evil. Just tick through a list of 20th-century villains — there’s no way this guy could crack the top 50, let alone vie for the title of history’s greatest monster.

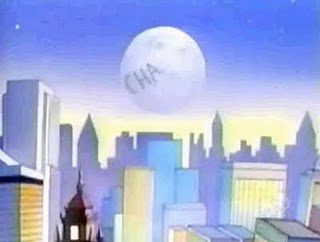

The villain Nicolae Carpathia probably reminds of more than any other is Chairface Chippendale, from one of my favorite episodes of The Tick — a warped parody of superhero comics. Chairface, a supervillain, constructs a giant heat ray he plans to use to carve his name on the moon. Our heroes, of course, rush to stop him, but the Tick struggles to make sense of this grandly strange act of supervillainy, asking his sidekick, Arthur, if carving your name on the moon is even illegal.

The villain Nicolae Carpathia probably reminds of more than any other is Chairface Chippendale, from one of my favorite episodes of The Tick — a warped parody of superhero comics. Chairface, a supervillain, constructs a giant heat ray he plans to use to carve his name on the moon. Our heroes, of course, rush to stop him, but the Tick struggles to make sense of this grandly strange act of supervillainy, asking his sidekick, Arthur, if carving your name on the moon is even illegal.

“It’s just wrong,” Arthur says, and he’s surely right about that. Defacing the moon would be an act of planetary vandalism. (Just think of it in Kantian terms — what if everyone built a giant heat ray to carve their names on the moon?) But the Tick’s confusion was understandable, too. Chairface’s scheme was surely, in some sense, evil, but in an oddly non-predatory, non-cruel way.

It was good that the heroes stopped him (if not quite in time — for the rest of the series the first three letters, “CHA,” could be seen whenever the moon rose over The City), but if Chairface had succeeded in his evil plan it wouldn’t have been the end of the world.

Much of Nicolae’s master plan seems similar to the oddball supervillainy of Chairface Chippendale. It’s more like some annoying brand of global performance art than any recognizable form of tyranny.

One world language? Why? And also, how? Seriously, how is he supposed to pull that off in less than seven years? And how is it possible to imagine, let alone accept, that this would be an overwhelmingly popular plan? Repressive regimes have sometimes outlawed minority languages as a kind of linguistic imperialism or as part of their ethnic cleansing efforts, but ethnic cleansing — a hallmark of cruel tyrants for millennia — seems beyond the scope of Nicolae’s oddball evil.

And that, again, is my point here. Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins’ Antichrist just doesn’t seem nearly as menacing or evil as the dozens of thuggish rulers who were fixtures in the news when these books were written. The 1990s were marked by the rise of nasty post-Cold War conflicts reasserting themselves all over the globe and in every one of those there was one or more beastly leaders who were more vicious, brutal and evil than the supposedly ultimate evil portrayed in these books. Nicolae Carpathia doesn’t just represent a failure of imagination, he represents a failure to pay attention to current events.

The authors’ inability to understand and portray a convincing Antichrist is also closely linked to their inability to understand a convincing Christ. That’s a product of their theology. Premillennial dispensationalism dispenses with Jesus’ life and teachings — relegating one to the irrelevant past and the other to the irrelevant future. And it regards Jesus’ death and resurrection — what most Christians consider, in Paul’s word, his essential and central “victory” — as the failure of God’s Plan A, requiring the correction of Plan B when Jesus will return in his second and third comings to remedy the problem by force.

In other words, what other Christians regard as a once-and-for-all showdown between love and power at Calvary, PMDs view as a Round 1 loss to be made up for in Round 2, when power gets defeated not by love, but by an even greater power. That suggests a moral universe in which the most important difference between good and evil is simply that good is stronger.

Such a view is bound to create an odd archvillain, as it does here. Nicolae is meant to be a tyrant, but the authors don’t really have a problem with tyranny per se — they’re awaiting the triumphant totalitarian reign of Jesus in the Millennium. Nicolae’s proposed New Age Talibanism is portrayed as evil not because totalitarianism and Talibanism are wrong in themselves, but because they’re reserved for the divine dictatorship of the coming age.

Anyway, this longish tangent results from the passage we’re encountering next in Chapter 13 of Tribulation Force, which also seems like a longish tangent until you realize that it isn’t meant as a tangent at all. What we find here in this seemingly trivial discussion between Rayford and Hattie is intended to be a glimpse into the central priorities of L&J’s Antichrist. Those priorities — the essence of his evil plans — are these: manipulating Rayford to work for him and shrewdly conspiring to have Air Force One repainted with his own logo.

It’s not quite carving your name on the moon with a giant heat ray, but it’s close.

Hattie finally explains Nicolae’s diabolical anonymous-flowers plan — an explanation that makes little sense — and she lays out for Rayford the Antichrist’s theory of global domination through executive aircraft. We’ll get to all that in more detail next week when we look at their conversation more closely, but for now I just want to focus on one exchange.

Rayford, a member of a secret guerrilla force sworn to oppose the Antichrist, has arranged this private meeting with Hattie Durham, the Antichrist’s Girl Friday and closest personal assistant. This is a golden opportunity for Rayford and the Tribulation Force to find out all they can about Nicolae’s plans, so he’s determined to make the most of it:

“Hattie, I want you to tell me about the flowers and candy.”

He bullies her into admitting she sent them on Nicolae’s behalf and Rayford, who’s meant to be viewed as the smart one in this conversation, interprets this to mean that Nicolae is “pursuing” Chloe romantically. Hattie quickly corrects this misimpression:

“He’s not pursuing her, Rayford! He’s seeing someone.”

“What does that mean?”

“He has a relationship.”

“Anybody we know?” Rayford gave her a disgusted look.

Hattie seemed to be fighting a grin. “It’s safe to say we’re an item …”

Here is further evidence that Nicolae just simply is not the Most Evil Person Ever. He’s not even the worst guy Hattie’s dated this year. Just look at Rayford, yet again, berating her and constantly expressing his “disgust.” Contrast that with her new beau who, so far, seems to be a stand-up guy. He’s given her confidence and treats her with respect. She seems happier than she has been in a long time.

I suppose we’re meant to regard Hattie as a “fallen woman” now due to her implied sexual relationship with Nicolae. I think the authors expect us to recoil from this — ZOMG! sin! — and to regard it as a sign of Nicolae’s ultimate evilness. But it seems a bit of a leap, even following the strictest and most conservative Christian sexual ethics, to consider a single woman and a single man in an apparently committed, monogamous relationship as the worst evil imaginable. It’s nowhere near as beastly as I would have expected the Antichrist’s personal life to be. I would have guessed the Antichrist to be a cruel, predatory user of women — physically and emotionally abusive, manipulative, unfaithful, using his mind-mojo like roofies in pursuit of debasing debaucheries that would have made Caligula blush with shame.

Instead he seems, well, caring. He’s apparently the kind of man for whom it would be unthinkable to pursue another woman when he’s in a “relationship.” And he rescued Hattie from something much worse — from a cruel, emotionally abusive pseudo-relationship with a contemptuous and self-righteously manipulative married man. By all accounts, Nicolae is treating Hattie with more love and respect than Rayford ever showed her. He’s treating Hattie better, in fact, than Rayford ever treated Irene.

I know several people who have an ex they refer to as “The Antichrist” and I’ve seen or heard the reasons these exes have earned that nickname. All of those real-world people seem more evil to me than Nicolae Carpathia does so far.

Later on in the series, when Nicolae transforms into more of a cackling, mustache-twirling fiend — bombing cities and fisting pigs and such — Hattie’s situation becomes much worse. If the authors had been at all interested in things like themes or metaphors, her relationship with Nicolae could have served as an illustration of evil’s seductive charm — at first innocently attractive, then corrupting and enslaving. But that would have involved portraying Hattie — and by extension all others deceived by the Antichrist — as a reasonable and responsible human being with whom we could sympathize. It would have meant trying to understand why the lure of this man seemed attractive, why he made such a convincing and persuasive-seeming counterfeit Messiah.

But as much as LaHaye & Jenkins like to pretend that they’re interested in warning against such deception and seduction, that’s not really what they’re about. They’re not saying, “Dear Reader, don’t be left behind and don’t be drawn in by the deceptions of the coming Antichrist.” Their real message, instead, is that those left behind to tribulation and damnation are, like Hattie, dirty, dirty whores who deserve what’s coming to them.

This is why I find it hard to believe the authors’ claims that these books are meant to be evangelistic. When your main method of evangelism is slut-shaming, I can’t believe you’re really interested in sharing the good news of salvation.

Contrast L&J’s contempt for Hattie with the far more human and sympathetic portrayal of “Patty Myers,” the hero of Donald W. Thompson’s classic low-budget 1970s Rapture movies (starting with A Thief in the Night).

Thompson cared about Patty and he wanted his audience to care about Patty — both as an individual and as a representative of all those who he believed were soon to suffer under the reign of the Antichrist. Thompson wanted Patty and all those others to be saved — in every sense. Like L&J, Thompson was a propagandist of heresies and a promoter of abominably antibiblical theology. But unlike L&J he didn’t also come across as a sociopath.