The reference to “Bad Jackie” in the title here is to a post or parable from back in 2010, Jackie at the Crossroads. I refer back to that a lot because it’s my best attempt to describe something that happens to all of us: We find out we were misinformed. And when we realize that, we have a choice to make. We can take the opportunity to learn, even if that involves the minor embarrassment of admitting that we were misinformed. Or we can double-down, defending ourselves and projecting ourselves to others as people who are never wrong.

This often happens in seemingly small ways involving minor points or trivia, rumors, or urban legends. It can be some small thing we’d heard or read somewhere and innocently believed. But even if the substance of that misconception is inconsequential, the choice we make when we have the chance to learn better is not. It’s the kind of decision that forms our habits, which in turn forms our character.

In this parable of Jackie at the Crossroads, the difference between a Good Jackie and a Bad Jackie is partly that Good Jackie is willing to admit that she’d been misinformed and to learn better, while Bad Jackie doubles-down, angrily defending her misconception. That’s a crossroads because it changes the nature of the thing. Up until that moment, both versions of Jackie can be said to be mostly innocent. They have been deceived, led astray. If we’re feeling ungenerous, we might say they’ve been gullible or naive or not as vigilantly skeptical as we might think everyone ought to be at all times, but mainly they’re guilty of nothing more than the human condition. At this point, their fault is that they’ve trusted some source that was not trustworthy, and when that happens — as it does and will for all of us at some point — the guilt ought to lie primarily with the untrustworthy source, not with those who have been tricked by it.

In this parable of Jackie at the Crossroads, the difference between a Good Jackie and a Bad Jackie is partly that Good Jackie is willing to admit that she’d been misinformed and to learn better, while Bad Jackie doubles-down, angrily defending her misconception. That’s a crossroads because it changes the nature of the thing. Up until that moment, both versions of Jackie can be said to be mostly innocent. They have been deceived, led astray. If we’re feeling ungenerous, we might say they’ve been gullible or naive or not as vigilantly skeptical as we might think everyone ought to be at all times, but mainly they’re guilty of nothing more than the human condition. At this point, their fault is that they’ve trusted some source that was not trustworthy, and when that happens — as it does and will for all of us at some point — the guilt ought to lie primarily with the untrustworthy source, not with those who have been tricked by it.

The choice to double-down on that untrustworthy untruth, though, changes one’s relationship to that falsehood. It changes you from being its victim to being its champion. It means that you are no longer merely deceived, but that you are choosing to deceive others — that you have decided that leading others astray would be, for whatever reason, preferable to admitting that you’d ever been led astray yourself.

And that’s the difference between the two Jackies in our parable. It’s the difference between Good and Bad.

In that story, Good Jackie found it easier to admit she’d been honestly deceived because she had been more honestly deceived. She’d believed the urban legend about the deadly South American airport spiders because her co-worker had insisted that she’d read about it in a magazine and that a friend’s cousin knew the person who died from being bitten. Those details had made the story more convincing to Good Jackie, but she’s later able to recognize that those details were dishonest embellishments made by her co-worker.

But when Bad Jackie had repeated that same story, she had, almost unconsciously, appropriated those claims for herself. She had assured others that the story was true because she had read it in a magazine, and that her friend’s cousin, or her cousin’s friend, personally knew the victim. Those claims were not true, but when she had made those false claims, she didn’t really feel like she was lying. It was more that she’d just gotten wrapped up in how she’d learned that this kind of story is supposed to be told. After you explain the part about the deadly spiders living under the toilet seats in airport bathrooms, you get to the part where you underscore the impact of that by explaining that you’d read this in a respectable magazine.

Such embellishments do, indeed, make for a more effective story, but I think they also reveal something crucially important about the character of the storyteller. This is a red flag — a warning sign that deserves our attention.

So pay attention to this, because it’s important. It’s a way to prevent becoming misinformed and a way to identify people who do not deserve your trust.

You’re talking to a friend or reading Facebook and you find you’re being told some wild story. Pay attention to the details about the source of that story. The difference is subtle, but it’s hugely revealing.

Sometimes you will hear something like this: “Scientists have found Joshua’s missing day.” Or like this: “The CEO of Procter & Gamble was on Oprah and said that part of their profits go to the Church of Satan.”

And when you hear that, you are dealing with someone who has been deceived. The person passing along this misinformation has been misled — perhaps mostly innocently.

But sometimes you will hear, instead, something like this: “A scientist told me that they’ve found Joshua’s missing day.” Or like this: “I saw the CEO of Procter & Gamble on Oprah …”

And when you hear that, you are dealing with someone who is trying to deceive you. The person passing along that misinformation is lying to you. This is an untrustworthy person — someone who is either deliberately lying, or else who is “bullshitting” in the Frankfurt sense of the word, someone who is wholly unconcerned with the truth or falsehood of anything they say. This is someone who, in Douglass’ phrase, requires heat, not more light.

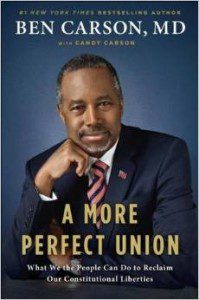

Which brings us to Ben Carson, the distinguished neurosurgeon now reinventing himself as a right-wing politician.

Ben Carson is Bad Jackie. He is doubling-down on his misconceptions because, like that version of Jackie, he has invested his own integrity and identity in them. Carson has said a host of outrageous, inaccurate and untrue things. Doug Muder offers a partial run-down of some of them:

The Holocaust wouldn’t have happened if Germany’s Jews had been armed; anarchy might force the 2016 elections to be cancelled; Russian president Putin, Palestinian leader Abbas, and Iranian leader Khamenei were all students together in 1968; Medicare and Medicaid fraud amounts to half a trillion dollars; Satan motivated Darwin to create the theory of evolution; and the signers of the Declaration of Independence had no elected office experience. He found fault with the victims of a mass shooting. He told Fox News’ Megyn Kelly: “I never saw a body with bullet holes that was more devastating than taking the right to arm ourselves away.” He wants to use the Department of Education to police liberal (but not conservative) bias at colleges and universities (and justified the need for such policing by citing an event that didn’t quite happen the way he claimed).

(Muder provides links for all of those, click through to his post for the full backgrounds. See also this list of Carson’s untrue statements from Kevin Drum.)

One often gets the sense that many of these stranger statements involve Carson repeating misinformation he’s received from elsewhere. He says these things with the attitude of someone accustomed to spending most of his time in a community of misconception where these ideas are generally “known” as common knowledge — things that do not need to be examined or scrutinized because they are simply known and accepted and circulated within that community. That’s part of why Carson often comes across as indignantly startled or defensive when he is challenged to verify any of these claims.

But it’s more than simply that with Ben Carson. He has not been passing along this misinformation as someone who was, himself, innocently deceived. He has consistently gone beyond that, appropriating the details of these claims for himself by adding as embellishment and flourish the claims that he, personally, can assure you of the truth of these claims because their truth has been verified to and by him personally.

Many of the odd things he has said might be widely shared and believed by other members of his primary community of misconception, but when most of those people repeat such misconceptions, they do so without inserting themselves as the supposed source — without staking the credibility of the claim they’re repeating to their own credibility. They’ll tell you that they heard it somewhere or read it somewhere from some scientist or something. Ben Carson will tell you that he spoke to the scientist personally, because he’s someone who regularly does that, routinely dazzling those scientists with his superior intellect and leaving them speechless because he is able to cut through all the nonsense of their supposed expertise.

That’s the red flag. And in Carson’s case it’s particularly egregious because of the common theme and common thread he weaves through his retelling of all these stories. That theme is this: the greatness of Ben Carson. That is the message he is constantly, urgently, desperately trying to convey: Me, me, me.

And that separates Carson from most of the people you’ll hear sharing his misconceptions about evolution, or addiction, or poverty, or whatever else the apparent subject may be. Most of the people passing along urban legends that supposedly disprove evolution do so because they’re trying to convince you not to “believe” in evolution. Carson recasts those legends into something else — stories meant to convince you that he, Ben Carson, is superior to anyone who disagrees with his misconceptions.

If there’s a moment at the crossroads that separates Good Jackie from Bad Jackie, Ben Carson passed that crossroads a long way back. This is a look at the dismal, foolish future that awaits anyone who has decided that they have never entertained any misconceptions and that they can never be wrong.

This is what an untrustworthy person looks like.