We evangelical-type Christians are big on conversion. It’s one of our defining traits — “conversionism” is part of David Bebbington’s widely cited “quadrilateral” definition of evangelicalism. Ye must be born again, we say. You need to come to Jesus, get saved, convert.

This conversion is a big deal, which is why it tends to form the basis of the “personal testimonies” we ritually share with one another in our evangelical Christian communities. Tell us about the moment when you got saved, the moment when you were born again, when you repented of your former life and everything changed.

The problem, though, is that for most of us, everything didn’t change. This is especially true for those of us who grew up within evangelical churches. We “got saved” as children, which doesn’t give us much of a dramatic backstory of an earlier life of wayward wickedness. We weren’t converted out of anything other than the same evangelical Christianity we eventually came to accept as our own. As I’ve said before, when those of us who were raised within evangelical Christianity are asked to give a “personal testimony” recounting our conversion, it’s like being a third-generation immigrant and being asked to tell the story about when your boat arrived at Ellis Island. We don’t have that story. We were born here.

Our stories won’t do. They are, at some level, unacceptable as conversion stories. For conversion stories to work, they need a stark contrast between before and after, and you can’t supply that if you accepted Jesus as your personal savior at Vacation Bible School when you were 6 years old.

The problem with such undramatic personal testimonies is not that they cast doubt on our personal legitimacy as second-generation born-again Christians, but that they cast doubt on the legitimacy of born-again Christianity and conversionism as a whole.

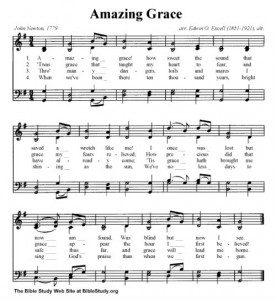

Conversionism needs drama. It needs the stark contrast of pre-conversion wickedness and post-conversion piety. It needs the arc of redemption we sing about in my least-favorite verse of “Amazing Grace”:

Amazing grace! How sweet the sound

That saved a wretch like me!

I once was lost, but now am found;

Was blind, but now I see.

Without that pre-conversion wretchedness, blindness and lostness, it’s just not the same. Without the contrast between our former blindness and our latter sight, we can’t be quite as confident that some drastic, eternity-shaping change — the most important moment in anyone’s life — has really occurred.

The author of “Amazing Grace” provides the model of a perfect evangelical conversion story. John Newton had been a wicked man — a slave-trader, a kidnapper who trafficked in human flesh. But then he got saved and was born again — transformed from wretched wickedness into glorious righteousness. Newton became an abolitionist, a crusader against the very evil he had, prior to his conversion, carried out.

The author of “Amazing Grace” provides the model of a perfect evangelical conversion story. John Newton had been a wicked man — a slave-trader, a kidnapper who trafficked in human flesh. But then he got saved and was born again — transformed from wretched wickedness into glorious righteousness. Newton became an abolitionist, a crusader against the very evil he had, prior to his conversion, carried out.

Most of us don’t really have a conversion story that offers that kind of stark change. In fact, John Newton himself didn’t have such a story. He really was a slaver. He was an oppressive, predatory, money-chasing exploiter of people. And then he became a born-again Christian, he asked God to forgive his sins and experienced a moment of conversion, after which … he continued to work as a slaver. For years.

Newton gradually changed and really did, decades later, become an admirable opponent of slavery. He was, eventually, converted out of that life and into something better — but that transformation was a journey, not the work of a single altar call. It was that decades-long journey of transformation that Newton describes in his beloved hymn.

We could still describe that long-term transformation as a kind of conversion, but it’s not the same thing as what evangelical Christianity tends to mean by conversionism.

“Aha!” the gatekeepers of tribal evangelicalism cry, “So you admit that you’re not really an evangelical! You fail to affirm Bebbington’s test of “conversionism!”

Well, it depends. It depends on what it is you’re talking about being converted from and what it is you’re talking about being converted to.

Back on those church youth group retreats I had a lousy, unsatisfactory personal testimony. It failed as a conversion narrative because it lacked the dramatic contrast everyone wanted to see affirmed. I’d gotten saved as a small child, right there at that church, and then, afterward, I continued attending that church. There was no big dramatic change to confirm to us all the immense significance of that life-altering born-again experience.

But now, though, years later, I’ve got a much more compelling story. I really have changed, dramatically, from the good little white evangelical in that church youth group. That’s a story of conversion — conversion from one thing into something else. It’s my personal testimony of the transforming power of God unto salvation.

That may not be the kind of conversion story the gatekeepers are looking for, but it’s a true story, and that, I think, makes it a better one.