Nicolae: The Rise of Antichrist; pp. 308-310

Bruce Barnes died in the final pages of the previous book in the series. He had contracted some fever while preaching the bad news of his gospel overseas somewhere and was rushed to the local hospital on his return to the former United States. Bruce was in a coma at Northwest Community Hospital in Arlington Heights when that facility was suddenly and inexplicably attacked by the Antichrist’s Global Community Air Force.

I’m still not sure whether Bruce died from the destruction of the hospital or if he coincidentally died from his tropical disease just before or during the bombing. Either way, though, that’s where and when he died, and where Rayford Steele apparently last saw Bruce’s body, lying under a sheet in a “makeshift outdoor morgue,” just one victim among countless others — “body after body laid out in a neat row and covered.”

That was more than 300 pages ago. How much time has passed, story-wise, is a bit fuzzy. It’s a couple of weeks, at least — time enough for Rayford to have returned to New Babylon for a bit before flying back to Milwaukee, and time enough for Buck Williams to have another of his oddly detached spy-thriller subplot adventures.

Now, let’s say around two weeks later, Bruce’s body is back at New Hope Village Church. It’s the morning of his Sunday-service memorial and Rayford is getting ready to preach his big sermon:

Fifty minutes before the service [Rayford] signaled the funeral director to move the casket into the sanctuary and open it.

Rayford was in Bruce’s office when the funeral director hurried back to him. “Sir, are you sure you still want me to do that? The sanctuary is full to overflowing already.”

Rayford didn’t doubt him but followed him to look for himself. He peeked through the platform door. It would have been inappropriate to open the casket in front of all those people. Had Bruce’s body been on display, waiting for them when they arrived, that would have been one thing. “Just wheel the closed coffin out there,” Rayford said. “We’ll schedule a viewing later.”

This later viewing will be scheduled by someone, probably Loretta. But Rayford, as Bruce’s extra-special friend, decides to have an extra-special viewing before then, just for himself.

As Rayford headed back to the office, he and the funeral director came upon the casket and the attendants in an otherwise empty corridor that led to the platform. Rayford was overcome with a sudden urge. “Could you open it just for me, briefly?”

“Certainly, sir, if you would avert your eyes a moment.”

Rayford turned his back and heard the lid open and the movement of the material.

“All right, sir,” the director said.

Here’s my question: Where has Bruce Barnes been all this time?

That’s really two questions, one logistical, the other theological. And the authors don’t seem to have given much thought to either one.

Back at the end of the previous book, Rayford had asked a nurse at the bombed-out hospital to help him find Bruce’s body. She lifted the sheet to show Rayford just long enough for him to conclude that, yep, that’s Bruce and, yep, he’s dead. At which point Rayford turned around and left, heading back to where Buck, Chloe, and Amanda were waiting so they could have one of their trademark end-of-the-book group hugs.

This passage, 300-some pages into the following book, is the first mention of a funeral director — or of any attempt to keep track of Bruce’s body in the intervening time.

I don’t mean to be morbid here, but that intervening time, you’ll recall, also involved the nuclear destruction of O’Hare International Airport and the entire city of Chicago. It also involved the nuclear destruction of New York, Washington, Dallas, San Francisco, and apparently almost every other major city, although those mass-murdering calamities wouldn’t have the same effect on the point I’m trying to make here, which is that the whole system for handling, managing and storing the remains of the recently deceased might be a bit overtaxed just now in and around Cook County, Illinois.

That would be true even if we were dealing only with the mass-casualty incident at the hospital, where Bruce’s body was last seen laid out along with every other recoverable victim in that attack — every patient and all but three employees, we were told. The bodies of those victims couldn’t be taken to the morgue at the hospital because the hospital was gone — a smoldering pile of rubble. And they couldn’t be taken to the Cook County ME’s office on Harrison Street in Chicago because there’s no longer any Cook County ME’s office, no longer any Harrison Street, and no longer any Chicago.

Apparently someone, probably Loretta, arranged to have Bruce’s body collected from the hospital and stored by some funeral home in the wholly unscathed suburbs near the church. Maybe that’s possible, but it would have been far different from the routine procedure described here in the pages of Nicolae. Every such facility would, after all, be dealing with an unprecedented flood of bodies — a worse crisis for them than even all the plane crashes and automobile accidents that overwhelmed them in the aftermath of the Event.

And so, once again, the weirdest thing about this scene in the book is the impossible mundane normalcy of it. All the incomprehensibly huge events of the previous two weeks of this story no longer seem to have happened at all. “The sanctuary is full to overflowing” of people mourning the death of Bruce Barnes — and exclusively the death of Bruce Barnes, not the deaths of any of the hundreds of others who died alongside him nor any of the millions of others who died nearby in the following days. Those people aren’t being mourned at all, by anyone, in this book. It’s as though no one other than Bruce Barnes had recently died.

The funeral director acts as though Bruce’s is the only funeral he has to deal with because, abruptly, it is. All that stuff that just happened has just as suddenly unhappened.

Saying that continuity and world-building are not Jerry Jenkins’ strong suit would be like saying the Great Wall of China is not short, but, again, this epic failure of world-building isn’t entirely Jenkins’ fault. It’s a necessary aspect of the “Bible prophecy” framework provided for him by Tim LaHaye. In LaHaye’s scheme, the End Times consists of a string of unconnected, discrete events that must occur, in sequence, in fulfillment of “Bible prophecy.” That sequence of events is unimaginable and unportrayable if we stop to dwell on the consequences and implications of any of them in turn. The fulfillment of one prophecy in the sequence would seem to preclude the possible fulfillment of the next one. I suppose a more imaginative writer might have viewed this as a challenge and worked to come up with ways to depict this sequence of events such that one flowed into the next. Jenkins wasn’t up to that challenge, so instead he took the extraordinary measure of having each prophesied event happen in a self-contained vacuum, then having it un-happen as his story moves briskly along to the next item in the sequence.

The result is, frankly, bewildering. Is Chicago still there? We simply don’t know. A few chapters ago we read that it was destroyed, and during those chapters, Chicago was no more. But here, now, on page 310, we readers cannot be sure that’s still the case. It often isn’t in these books. Whole cities rise and fall and reappear. Nations are disbanded and reformed in the flip of the page between chapters.

If a tree falls in the forest, and the authors later forget it fell, is it still standing? I have no idea.

But the logistical question of where Bruce has been all this time is not as difficult, for the authors, as the far trickier theological aspect of that question.

Think back to all of those piles of clothes (and prosthetics, toupees, etc.) left behind after the Rapture, when all the real, true Christians were whisked off to Heaven — body and soul. That bodily Rapture corresponds with the Christian belief in a bodily resurrection, along the lines of what we Christians believe the book of Job affirms in that passage that “amazed” Buck Williams last week: “I know that my redeemer liveth, and that he shall stand at the latter day upon the earth: And though after my skin worms destroy this body, yet in my flesh shall I see God” (quoted here in the KJV because Handel).

But Bruce Barnes’ post-Rapture death raises the spectre, as it were, of the body-soul dualism that L&J seemed to reject with their bodily Rapture:

Bruce looked less alive and even more like the shell Rayford knew this body to be than he had under the shroud outside the demolished hospital where Rayford had found him. Whether it was the lighting, the passage of time, or his own grief and fatigue, Rayford did not know. This, he knew, was merely the earthly house of his dear friend. Bruce was gone. The likeness that lay here was just a reflection of the man he once was. Rayford thanked the director and headed back to the office.

He was glad he had taken that last look. It wasn’t that he needed closure, as so many said of such a viewing. He had simply feared that the shock of Bruce appearing so lifeless at a corporate viewing might render him speechless. But it didn’t now.

Manly men don’t need “closure,” of course. That’s for the womenfolk. But if “Bruce was gone” and all that was left was the “shell” of his “earthly house,” then where did Bruce go?* If this isn’t him, but merely the mortal coil he’s shuffled off, then where is he? And what is he — this him that isn’t this?

That’s a tricky question for all Christians, of course, but it’s particularly hard for Rapture-enthusiasts like LaHaye and Jenkins. They can’t do what the rest of us do, which is turn to that strange little passage in 1 Thessalonians in which Paul tells us not to lose hope for those who have died, in which he seems to say that they have gone on ahead, but we will be reunited with them some day. “Encourage one another with these words,” Paul says. But Rapture-enthusiasts cannot do that because, for them, this passage is about the Rapture, and not about “those who have died.”

In fact, for Rapture-enthusiasts, almost every biblical passage about death is reinterpreted as Rapture instructions. And that leaves them sorely lacking in knowing what to say or think about death when they encounter it.

If you really want to take a dive through the looking glass, start googling around to see what Rapture-believers think about what happens to the souls of everyone who dies before the Rapture, and to see the often heated arguments about whether or not that’s the same as what happens to the souls of those, like Bruce, who die during the Rapture. You’ll find a darkly fascinating mix of emphatic certainty and wild speculation, with no distinction between the two. (Here’s a Google search for “Rapture + cremation,” that’ll get you started if you enjoy that sort of thing.)

I suspect that part of the reason L&J only touch on this vaguely here is because they’re hoping to avoid getting bogged down in this whole ongoing when-do-which-souls-go-where argument within the “Bible-prophecy” guild. But I suspect the main reason that the disposition of Bruce’s soul is addressed so vaguely here is that LaHaye and Jenkins don’t really know what they think about that.

Where has Bruce been this whole time? Whether we treat that question logistically or theologically, the authors cannot answer it because they haven’t given it any thought. At all.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – –

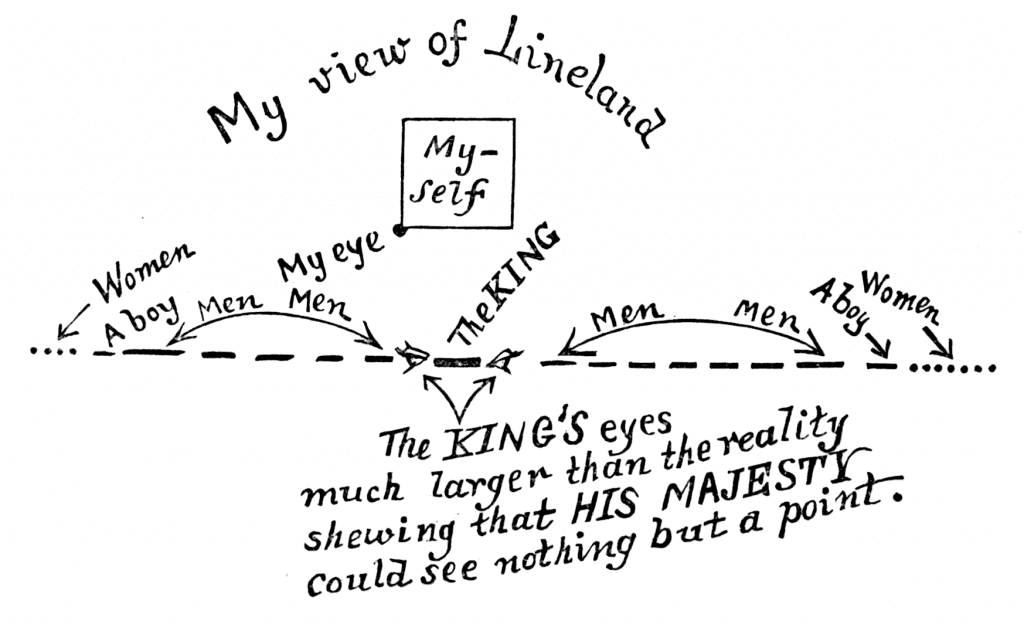

* It’s perfectly fair, at this point, for you to ask what I think happened to Bruce when he died, and thus what happens to the rest of us. The short answer is that, like everyone else, I don’t know. The undiscover’d country from whose bourn no traveller returns and all that. But if you want to know what I think or suspect/expect/believe/hope, well, have you ever read Flatland? …