• Erik Loomis visits the American grave of Sarah Bagley. Bagley was a “mill girl” working in the textile factories of Lowell, Massachusetts, starting in the 1830s. As Loomis says, she soon became involved in early labor efforts to “reform” conditions for women working in those mills:

Bagley helped found the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association in 1844. Other mill towns such as Manchester, New Hampshire formed their own Female Labor Reform Associations. Bagley led a campaign to demand the Massachusetts government hold hearings about conditions in the mills. By 1845, 1,150 Lowell workers had signed petitions to demand the hearings, about three-fourths of them women. On February 13, 1845, Bagley’s organizing paid off and the state of Massachusetts held hearings on reducing the workday in the state’s textile mills to ten hours a day. Six women testified, including Bagley. She said, “The chief evil, so far as health is concerned, is the shortness of time allowed for meals. The next evil is the length of time employed.” Bagley and other women would use their perceived vulnerability as women to make the ten-hour argument. Said E.S., a Mill Girl, a shorter work day would lead “to the improvement of the condition of women in particular” that would allow them to become educated and then become better mothers. Bagley built on these arguments by arguing that Sunday work undermined women’s morality because they could not go to church. But in 1846, the Massachusetts legislature voted to reject the workers’ demands. Massachusetts prioritized the desires of employers over any form of social justice. However, the owners did agree to reduce the hours to eleven a day in 1853 as the women continued pressuring them.

Consider for a moment that the right not to be forced to work 11-hour days was won by people who managed to organize and mobilize despite the fact that they were underpaid and working 11 hours a day.

Bagley’s story is also very difficult to square with the “Christian nation” mythology David Barton has turned into Republican Party dogma. This was Massachusetts — the original “city on a hill” of Pilgrim’s pride. Yet legislators and wealthy mill owners were unanimously opposed to the idea that “mill girls” might have Sundays off.

Weekends weren’t handed down to us by the devout Founding Fathers, or by the benevolent patriarchs of Christian America. They were fought for tooth and nail and hard-won by tired, overworked “mill girls” and other workers.

• I don’t know much about Elmbrook, Wisconsin’s white evangelical mega-church, other than that its a white evangelical mega-church in, um, Wisconsin. So I don’t have any special insight into its now former head pastor, Brodie Swanson, who just resigned “amid revelations of infidelities with another church staffer, who also stepped down.”

I do know how about 81 percent of Elmbrook’s members voted in 2016. And I know why — because they’ve been told and retold, over and over, that their pastors were the arbiters of morality, and that morality as understood by those pastors required them to vote for the party that their Moral Authority pastors insisted, implicitly and explicitly and constantly, that it was their duty as Christians and as decent people to vote for.

I wonder if Wisconsin’s white evangelicals — like Pennsylvania’s white Catholics — are maybe getting a little bit tired of being instructed in how they must vote by Moral Authorities who seem to be less moral than those they’ve been lecturing all these years.

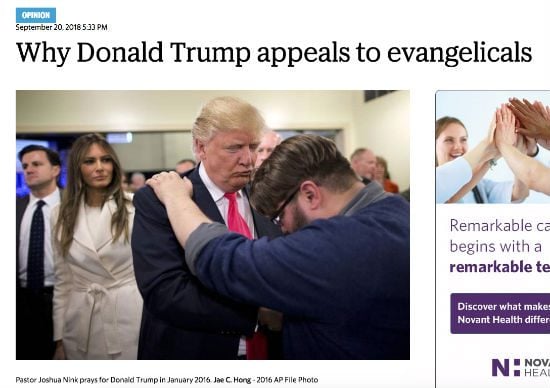

• Dana Ervin’s op-ed on “Why Donald Trump appeals to evangelicals” isn’t among the worst entries in this overlarge, overworked genre. I found this bit interesting:

The president has tapped into the evangelical psyche. Trump gets that evangelicals feel under siege in a society with rapidly changing laws and social standards about sex, abortion, marriage and gender identity. He is keenly aware evangelicals believe that unless America turns from its ways and embraces Israel, God will no longer bless this country.

That identifies the one-word answer most white evangelicals would give to explain their total support for Trump: “abortion.” But highlight that word in that sentence and the sentence becomes perverse:

Trump gets that evangelicals feel under siege in a society with rapidly changing laws and social standards about … abortion.

“Laws about … abortion” are, indeed, “rapidly changing.” They’re becoming more and more restrictive. The idea that the pro-Trump wave of white ethno-nationalist evangelical fervor is in response to their anti-abortionist doctrines being “under siege” just doesn’t reflect reality. At all.

This backlash is not about “rapidly changing laws and social standards.” It’s about changing demographics. It’s about “liberty and justice for all” starting, haltingly, to include people other than them.

Polite euphemisms about those who “feel under siege in a society with rapidly changing laws and social standards” are not inaccurate, per se, but the same exact phrase could be used, with the same timid imprecision, to explain the popularity of the second Klan in the early 20th century. The popularity of the Klan among white Americans was not an opaque riddle or mystery. Neither is Donald Trump’s appeal for white evangelicals.

• The New Republic isn’t generally someplace I expect to find what we evangelical types call a “personal testimony,” but that is what Bryan Mealer’s essay, “The Struggle for a New American Gospel” is.

Mealer’s story is not my story. Nor is Mike McHargue’s or Michael Gungor’s story identical to mine. But many parts of their stories, as conveyed by Mealer, resonate with me, as I expect they will for most ex-evangelicals (whether that ex-ness was chosen or imposed, or some messy combination of the two).

• I would dismiss this rant from Deadspin’s Albert Burneko as too caustically cynical and uncharitable to be believed. The problem, though, is that Burneko’s thesis better aligns with our current politics than almost any other theory. The current behavior of the current Republican Party completely conforms to his predictions — all that they do and say and all that they refuse to do or say. So.

• The artwork discussed here is about September 11, 2001, but since the essay is also Michael Stipe writing about Douglas Coupland, this may be the most 1990s thing I have read in … well, I guess in about 18 years. I am old, I am old, I shall wear my trousers rolled and try not to think about the fact that Murmur is now more distant to the present day than “Johnny B. Goode” was to “Radio Free Europe.”

• “Thoughts and prayers.”