“You say, ‘If we had lived in the days of our ancestors, we would not have taken part with them in shedding the blood of the prophets.’ … Therefore I send you prophets, sages, and scribes, some of whom you will kill and crucify, and some you will flog in your churches and pursue from town to town.” — Matthew 23

Sinead O’Connor was right. I need to say that now, in 2019, because I did not say that 26 years ago, in the fall of 1992. Instead, I just kind of fell in line — affirming and repeating what everyone else was saying.

But this isn’t about me. This isn’t about my reputation or my apology — although I’m obliged to offer such an apology nonetheless, because I was shamefully wrong. My reputation isn’t what matters here.

Nor, for that matter, is the reputation of Sinead O’Connor or of the many public figures whose ugly response to her in 1992 merits condemnation. Condemning those people now is easy, just as it’s easy for 2019 me to look back and condemn 1992 me.

That condemnation is necessary, but it can also be a trap — tempting us to say that “if we had lived in the days of our ancestors, we would not have taken part” and thereby to ignore all the ways we may be retracing their footsteps even now.

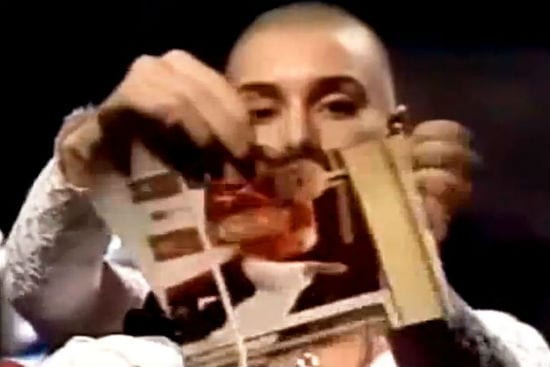

But first, 1992. What happened was that the Irish singer Sinead O’Connor was the musical guest on Saturday Night Live. She’d appeared on the show once before, in 1990, following the success of “Nothing Compares 2u.” She returned to SNL on October 3, 1992. No one remembers her opening number — a raw rendition of the old Loretta Lynn song “Success.” What made news was her second song.

O’Connor belted an unsettling, almost tuneless a capella rendition of Bob Marley’s “War.” She altered the lyrics slightly — starkly inserting a condemnation of “child abuse.” Twice.

When she reached the end — the lines about “the victory of good over evil” — she held up a photograph of Pope John Paul II, ripped it into pieces, and said “Fight the real enemy.”

She “told us the truth just as hard as she could” but, instead of listening — instead of even trying to listen — we attacked her for it. She was vilified and mocked and booed by about half of the country while the other half sadly shook our heads, lamenting that this poor young woman brought all this on herself with her inappropriate gestures. Those were our responses — either attacking her or blaming her for getting herself attacked.

That “our” is not quite all-inclusive. There were at least two factions of the public that understood exactly what she was telling us and recognized it to be true. The first of those groups were the victims on whose behalf she spoke — tens of thousands of them. But they had been stripped of all power to speak and no one was listening to them either.

The second group that recognized the truth of what she said was much smaller, but much more powerful. That group consisted of the perpetrators of the abuse O’Connor was condemning, and of the bishops and powerful church leaders who had been actively covering up for them for decades. This second group wasn’t interested in publicly acknowledging the truth of O’Connors protest. Instead, they sprang into action to ensure that the rest of us made enough noise to be unable to hear her — encouraging us to choose between those awful failures of condemnation or condescension.

For the record, I was in the latter camp — condescending dismissal. This was the hastily assembled official consensus of thoughtful moderates — which is to say of those who wished to think of themselves as thoughtful moderates. It was what all the Very Serious People were saying. And as is so often the case with the official consensus of the Very Serious People, it was less about rejecting the cruelty and bullying of the louder, angrier response than it was about asserting a desire not to be perceived as cruel and bullying.

This consensus involved an almost verbatim recitation of the “white moderate” response prophetically condemned in King’s epistle from Birmingham:

I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action;” who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for [other people’s] freedom. …

That generational echo is important. It illustrates again the enduring insight of Jesus’ rant in the Gospel of Matthew about our tendency to self-righteously say “If we had lived in the days of our ancestors …” then we would have listened to the prophets instead of killing them. We would have bothered to try to understand what they were telling us.

In 1992, a lot of us were sure that if we had lived in the days of 1963 Birmingham, then we “would not have taken part” with the cruel, violent backlash and the abuses of power that put Dr. King in jail. And we were just as sure that we would not have gone squishy like the “white moderates” he criticized — the Very Serious white preachers who wrote to dismissively praise his courage while ignoring the urgent truth his demonstrations were demonstrating.

But looking back at 1992 helps me see that I have far more in common with those white moderate pastors than I flattered myself into believing. It helps me to understand that they were probably a lot like me — bewildered and shocked at being confronted by a witness to an injustice the scope and magnitude of which exceeded their comprehension. They also would likely have witnessed that bearing of witness second-hand or third-hand — hearing of it as it was relayed and responded to in a rapidly ossifying consensus of condemnation. They also would have found it far simpler to repeat the reasonable-sounding reassurances of the Very Serious People, insisting that whatever it was King and his fellow protesters were trying to say, it was probably their own fault that no one was listening because their methods were so rudely confrontational that they were themselves responsible for inciting such opposition.

I get that. And, yes, on one level, such understanding makes it easier to forgive them. It reminds me that I, too, require the same measure of grace, and that it would be churlish and self-serving to seek such forgiveness for myself without also being willing to extend it to others.

But it also makes it ever more important not to forgive them too easily. Because recognizing that forgiving them is related to being forgiven myself makes such forgiveness, in a way, self-serving. And we shouldn’t complacently trust things that prove to be so conveniently self-serving.

Jesus’ point in Matthew 23 was not that we should be more charitable and forgiving to our ancestors, that we should cease condemning them for “shedding the blood of the prophets.” His point was that we have prophets among us right now and we’re still refusing to listen to them.

When we try to excuse our ancestors because they were “people of their time” and “they didn’t know any better” we ignore the fact that they could have known better. They had Moses and the prophets. If they did not listen to them, they wouldn’t have been convinced even if someone had risen from the dead.

“We had all the pieces. Why didn’t we get it sooner?”

That, again, is a line from the movie Spotlight. And what I’m saying here, again, is that “we” are all Michael Keaton in Spotlight.

Today, in 2019 — after Spotlight won its Oscars, and after the Boston Globe’s reporting that inspired the film, after the Pennsylvania Grand Jury report, and the Houston Chronicle’s recent series, after the investigation of the Magdalene laundries and the Ryan Report and the mass-graves at Tuam — we can see all the pieces far more clearly.

All those pieces were there in 1992, waiting to be seen. But we didn’t want to look at them and the vast majority of us didn’t have to look at them. We didn’t have to know, so we carried on not knowing.

Politely asking us to look wasn’t going to work. It does no good to politely ask people to pay attention to that which they’re choosing not to pay attention because they won’t hear you. They won’t listen. That’s what “not paying attention” means.

What such a situation requires, then, what it demands is something that will grab attention — something impolite and aggressive enough to force us to look. Such actions will never be as nuanced and detailed as a position paper. They will inevitably be perceived as rude, confrontational, and off-putting — the kind of thing that may well get one flogged in churches and chased from town to town.

For the great majority of those seeing such a thing, it will likely seem bewildering. Forced finally to look at “all the pieces” they will, at first, see only that — pieces. They won’t suddenly have all the answers, but they will be confronted with a host of new questions: Why is this person so upset all of a sudden? What are they going on about? What is it they want us to do?

This is the moment, and it’s usually just a moment. Hit or miss. The confused public — forced briefly to pay attention — will either pursue those questions, seeking answers to them. Or else they won’t.

Those answers are available if we are willing to do the obvious thing in the sacred space of that moment and direct all those questions to the very people who raised them — the weird bald girl or the kneeling football players or all of those people rudely blocking the highway north of St. Louis.

But those are tough questions with unpleasant answers. Those of us who are not directly affected by the injustice still won’t want to ask them and we still won’t have to ask them.

And just seconds after that moment, with astonishing rapidity, we’ll hear the comforting voices of the pre-written consensus, the reasonable-sounding song of the Very Serious People reassuring us that we do not need to trouble ourselves with asking those rabble-rousing prophets and sages and scribes what it was they were trying to get us to look at. We’ll swiftly be told that even if it might have been brave or commendably idealistic for those misguided souls to have interrupted us all like that, there’s no need to disturb ourselves overmuch because if it were anything really important those people would have gone through the proper channels. Even if we vaguely suspect we might abstractly agree with the goals they seek, it’s more important in that moment to condemn their methods. After all, whatever it was those folks were so upset about, whatever made them so upsetting to us, it’s their fault that it’s still a problem because they didn’t have the decency to go about addressing it in the right way. Shouldn’t we go about things in the right and proper way?

And just like that, the moment passes.

And the injustice continues for another year. Another two years. Another 10 years. Another generation.

“We” didn’t know. We could have known.

“We” don’t know. We could know. We can know.