I enjoy dark chocolate. I like almonds. I think dark chocolate and almonds, together, are delicious. I thus find the Mounds/Almond Joy dichotomy very frustrating.

If you’re not familiar with these confections, let me explain: Almond Joy’s got nuts. Mounds don’t.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7JSIRo9DjBA

That is one variable distinguishing between the two candies. If that were the only distinction between them, then just having these two options would be fine. Two candies: One with nuts, one without.

But this is not the only variable. (I don’t mean coconut, obviously. The coconut is a constant.) Almond Joy and Mounds also feature different kinds of chocolate. This is right there in the jingle: “Almond Joy’s got real milk chocolate … Mounds got deep dark chocolate.”

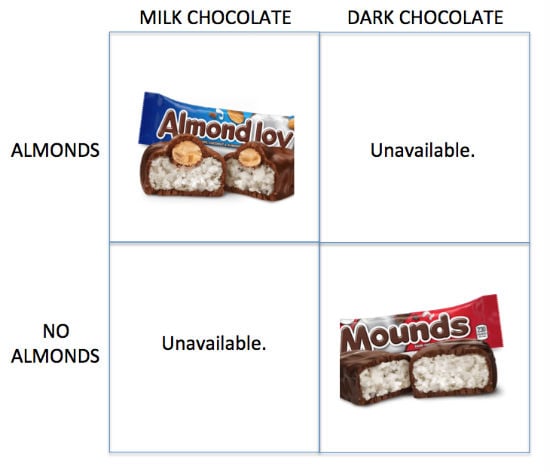

This second variable suggests the possible existence of not just two, but four candies. More than that, it suggests the necessary existence of all four candies. These options would seem to be logical, mathematical requirements even if the candy-makers themselves stubbornly refuse to offer them or even to acknowledge their absence:

- Milk chocolate with almonds (Almond Joy).

- Milk chocolate without almonds.

- Dark chocolate with almonds.

- Dark chocolate without almonds (Mounds).

We can chart these two variables out into quadrants, providing a stark visual demonstration of the theoretical, logical imperative for the as-yet-non-existent dark-chocolate Almond Joy:

Big Candy is denying us half of the options it seems ought to be available. This is annoying for those of us who prefer both almonds and dark chocolate. (I suppose it’s also frustrating for those who prefer milk chocolate without almonds, if there even are such people.)

Since taking over the brand from PeterPaul, Hershey has experimented with special-edition variants of Almond Joy. They’ve rolled out piña colada-and passion fruit-flavored versions and some kind of White Chocolate Key Lime monstrosity that I don’t even want to think about.

But the simplest, most obvious variant — Almond Joy with the same dark chocolate they’re already using for Mounds — is still being withheld from us.

I remain hopeful that someday Hershey will correct this oversight. Until then, those of us longing for dark chocolate with almonds are in a precarious spot. We’ve vested all of our hope in something that exists only in theory — a quadrant or category that elegant mathematical logic insists ought to exist, but that cannot be found as of yet here in reality.

I’m accustomed to that situation. Because of Matthew 25.

That passage is where we find the infamous parable of the “Sheep and the Goats” — the story in which Jesus finally gives us a straight answer to the question “What must I do to be saved?” and the stark, unambiguous reality of it is so unsettling that we’ve spent thousands of years now trying to weasel our way around it somehow.

The story is a soteriological nightmare — a textbook case of heretical Pelagianism proclaiming that salvation hinges on deeds and works. (Worse than that, even, because like many of Jesus’ sayings and stories it seems to teach, rather, that salvation for rich people hinges on deeds and works, while salvation for the poor is simply a given.)

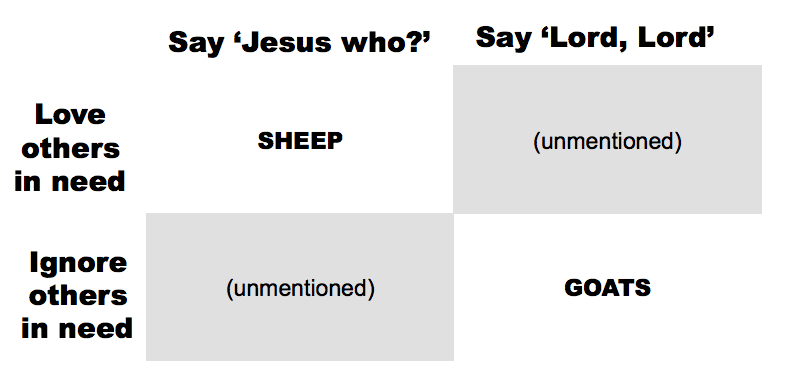

That’s all horrifying enough to our ideas of orthodox soteriology that we tend not to notice another strange aspect of this story. Its distinction between sheep and goats involves two variables — just like the Almond Joy/Mounds distinction above. The first, most important distinction is that the blessed “sheep” feed the hungry while the accursed “goats” do not. But something else distinguishes them: the “goats” all seem to recognize Jesus in this story, but not one of the “sheep” has any idea who this guy is.

Again, the second variable suggests that there ought to be four possibilities:

- Those who know Jesus but do not feed the hungry.

- Those who do not know Jesus but do feed the hungry.

- Those who know Jesus and feed the hungry.

- Those who do not know Jesus and do not feed the hungry.

But the story itself doesn’t include the last two categories. I’ve previously charted this out in quadrants, similar to our chocolate conundrum above:

This is a bit worrisome for those of us who regard ourselves as “Christians” — as people who look to Jesus and say, “Lord, Lord.” The story was troubling enough, because most of us “Christians” maybe probably have reason to suspect we’re not doing nearly enough of the feeding the hungry, caring for the sick, sheltering the homeless stuff it tells us is the basis for our potential salvation.

But then we realize that we can’t find ourselves in this story at all. We’re the milk-chocolate Mounds bars of this story, existing in theory but not actually present.

That suggests something about how we ought to think about salvation, and about evangelism. But, again, that’s not my main point here.

My main point here, rather, is that there really ought to be a dark-chocolate version of Almond Joy.