“By 1891, Elizabeth grew disillusioned with faith healing, because she viewed it as hooey. She consequently wrote a book attacking it in 1891, called Mrs. Whilling’s Faith Cure.”

That tantalizing tidbit comes from a New England Historical Society article about a traditional Maine delicacy I’d never heard of before: “The Needham, a Potato Candy Sacred and Peculiar to Maine.” It seems there’s enough chocolate, coconut, and powdered sugar in a needham that one hardly notices the room-temperature mashed potatoes that make up the bulk of Maine’s official “state treat.”

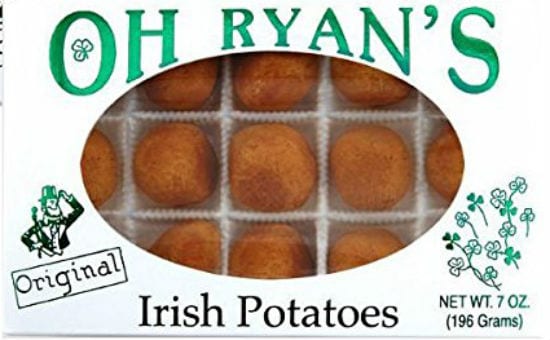

I’ll have to try one of those the next time I find myself up Down East. It sounds like Maine’s potato-infused version of a regional delicacy around here, the “Irish potato,” which, as Wikipedia says “is a traditional Philadelphia confection that, despite its name, is not from Ireland, and does not usually contain any potato.” Those delightful chewy gobs of coconut and cinnamon appear on Wawa counters every March and we always end up buying a box of Oh Ryan’s each year because that is just something one does around here. (I like them better than “salt water taffy” — another obligatory traditional regional candy that one somehow always ends up with a box of after anybody goes down the shore.)

I was surprised by the word “usually” in that Wikipedia entry — “does not usually contain any potato.” It seems some people make a variation of these that sounds like a smaller, round cinnamon needham. OK, then.

The strangest thing about needhams isn’t the mashed potato. It’s the name. The NE Historical Society explains:

In 1986, Maine writer John Gould described the needham as ‘sacred and peculiar’ to Maine. He told the commonly accepted story of how the candy originated sometime around 1872.

A candymaker, Mr. Seavey, introduced a new item when one of his cooks brought forth a chocolate-covered coconut cream with a secret ingredient — potato. He passed it about to see what Mr. Seavey, and others, thought of it. Significantly, the new candy had a square shape.

Mr. Seavey and others immediately approved the candy, but they didn’t know what to call it. Mr. Seavey said, “Let’s call ’em needhams, after the popular preacher,” according to Gould.

And so the candy became the needham, for a century a native Maine delicacy except for a few areas where it crossed the line into New Hampshire.

The popular preacher was George C. Needham, an Irish-born Protestant evangelist who became a follower of Dwight L. Moody and was briefly a popular tent-meeting and rescue-mission revivalist. Needham may have been “popular” in New England in 1872, but he’s since fallen into obscurity. He apparently wrote more than a dozen hymns, but I’d never heard of any of those either. He wrote a handful of books — including a hagiography of Charles H. Spurgeon, a couple of “humorous” collections of stories about the “Street Arabs and gutter snipes” (yeesh) he encountered in rescue missions, and a few early (1870s) “Bible prophecy” books detailing his belief that biblical arcana about the tabernacle proved that the Second Coming of Jesus was imminent.

After coming up nearly empty on a Google search to learn more about Needham, I turned to my physical library. I have an embarrassing number of books about 19th-century revivalism and evangelicalism but can’t find any mention of Needham in any of them. He seems, today, to be remembered only as the arbitrary namesake of that Maine confection.

So almost all I can tell you about “the popular preacher” comes from two sources. One is an August 1901 announcement of his revival meetings in the long-defunct weekly Cambridge Tribune:

George C. Needham was born In the south of Ireland, In the region near the lake of Killarney. He is one of four brothers, all of whom have distinguished themselves in evangelistic work. Rev. Thomas Needham is known as the “sailor preacher.” Rev. William E. Needham is styled the “artist preacher,” because he gives blackboard illustrations of his sermons, and Rev. Benjamin C. Needham is called the “farmer preacher” from the fact that he both farms and preaches. Rev. George C. Needham has made his home in Philadelphia for a good many years. During the summer months he carries on a tent work in that city. The tent in which Mr. Needham holds his revival meetings is a large one, having a seating capacity of nearly 800. … Mr Needham is assisted in his evangelistic work by his wife. They have been extensive travelers in the cause of religion. … Mr. Needham assisted the late Rev. Mr. Moody in his work of evangelization for a good many years. He is now associated with Rev. William Moody, the son of the great evangelist.

The other source is from six months later — Needham’s 1902 obituary in The New York Times. That obituary recounts an anecdote that Needham likely told in his tent-meeting revivals. Emily Burnham of the Bangor Daily News summarizes the story with an appropriate dose of skepticism:

In his obituary in The New York Times in February 1902 — among the only sources of information on the man, aside from his voluminous writings on spiritual matters — it states that he was born in Ireland in 1846. His obituary claims that when he was 10 years old he was put on a ship bound for South America, and was tortured by the captain and tattooed against his will during the long journey. Eventually Needham was taken ashore in Patagonia, where he claimed he was taken captive by “cannibal Indians” who were going to “make a feast of him,” but they stopped when they saw his tattoos.

(Given that there is absolutely no historical record of the Tehuelche people of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego ever practicing cannibalism in any form, this seems a particularly dubious and, unsurprisingly, racist claim.)

Needham was not the first evangelistic preacher to rely on dubious and racist anecdotes in his revivals. And he’s far from the last.

I’m frustrated that I was unable to learn more about George C. Needham because he seems like a fascinating transitional case-study in American white evangelicalism. His “Bible-prophecy” occultism predates the explosion of premillennial dispensationalist folklore that followed the publication of the Scofield Bible. And he was apparently working the “faith-healing” racket a full generation before the birth of Pentecostalism in the early 20th-century. I’m curious as to how Needham stitched together all of that — his proto-Rapture folklore, his 19th-century faith healing, his Spurgeonism and Moodyism. He seems like he may have been both an outdated relic and ahead of his time.

Needham apparently dropped the faith-healing stuff eventually, thanks to his wife, Elizabeth, who — as we saw way up at the top of this post — became convinced it was “hooey” and thus “wrote a book attacking it in 1891, called Mrs. Whilling’s Faith Cure.”

Googling to learn more about Elizabeth Needham can be tricky due to a far more (in)famous person with that same name, but I was able to find a nice online edition of Mrs. Whilling’s Faith Cure courtesy of the Ohio State Library.

It is, alas, quite awful. It’s a didactic tract more than a novel, and Mrs. Needham’s style of prose has not aged well. A taste:

Dr. Luther Large was a commanding character. His pleasing face arrested even a stranger’s attention. But his eyes were its chief feature. They were small, but of purest quality. As the opal gem under certain light emits fire, and at other angles of vision rays of mellow softness, so with those changing eyes. They flashed out one glance of sarcastic merriment on poor little Ruth Gentlee, and she wilted like a young June leaf under a sharp northeast wind. With lowered head, without another word, she turned and walked down the church aisle. The pastor’s eyes followed her, having instantly changed to their expression of yearning, fatherly tenderness.

All the names are like that: Large, Gentlee, Whilling, Sharpe, Noble, Middleman.* None of these are characters as much as spokespeople for varying points of view who all state their case, are corrected, and then admit the error of their thinking as each, in turn, bows before the superior biblical teaching of the opal-eyed Dr. Large.

If you’re wondering what the plot is, there isn’t much of one. Mrs. Whilling invites Dr. Large to conduct a series of weekly Bible studies addressing the craze for faith healing and the book provides a transcript of these meetings. The result is chapters that consist entirely of a late 19th-century white evangelical exegesis of James 5:14.

One gets the sense that Mrs. Needham felt that, as a woman, she lacked the spiritual authority to write a book of biblical interpretation, so instead she wrote a “novel” starring a male protagonist who could serve as her surrogate mouthpiece. I applaud the ingenuity of that, even if the execution turned out to be thuddingly dull.

Mrs. Whilling’s Faith Cure has been out of print for more than a century and deserves to stay that way. It’s not worth reviving in its original state.

But I think it could be rewritten and salvaged. We just need to kill off Dr. Large. He should be found dead in his locked study — the fire extinguished from his opal eyes — sometime just before the third meeting of his weekly Bible study. The various two-dimensional straw-man proponents of faith healing would thus be transformed into suspects to be interviewed — first separately, and then, ultimately, all at once in Mrs. Whilling’s spacious parlor — by (surprise twist!) amateur alienist Emma Reynolds Moody.

Not only would that be far more engaging and entertaining, but transforming this clumsily pedantic “novel” into a cozy whodunit would also allow us to explore motives behind the faith-healing hooey other than the only motive Mrs. Needham seems to recognize: insufficiently rigorous biblical exegesis.

Anyway, here is a recipe for Irish potato candy and here is a recipe for needhams.

– – – – – – – – – – – – –

* “Dr. Middleman” is the one character I wished we’d seen more of. Needham’s description of him is one of the very few places her book shows the kind of wit I was hoping for:

“He is a physician who practices medicine, but has sympathy with faith healing. His house is a kind of refuge for the professional healers when they get sick. They put themselves under his care till well.”