Almost every Gen X or older Millennial who grew up in white evangelicalism could tell some variation of the story Alex Morris tells here. They may not all realize they can tell this same story, but they lived through it just as surely as she did. Every white evangelical who lived through the 1980s lived through this change. Weirdly, though, only some of us seem to remember it.

Alex Morris remembers it. Here she describes her childhood within our white evangelical world:

I was raised a child of the Christian right. I know what they believe because the tenets of their faith are mine too. Growing up, I attended church at least twice a week and went to Bible camp every summer, singing songs about Christian martyrs who stood up to tyrants in the name of God. My brother and sister and I learned catechism and sang in the choir, but we also attended public school and played Little League and did community theater. We read C.S. Lewis but also Beverly Cleary. We listened to Amy Grant and Simon and Garfunkel. We were taught that evolution was a lie, with NPR playing in the background. We knew that women should submit to their husbands, but also that sex within the confines of marriage could be mind-blowingly good and that we should never be ashamed of our bodies. We felt that homosexuality was a sin, but we loved my mom’s Uncle Robert and his handsome boyfriend Ken. We knew that the Republican Party was the party of family values, but we weren’t particularly political. In Birmingham, Alabama, in the 1980s, Christianity was the culture; but for my family, it was much more. We believed in the Bible stories my mother read us over our eggs each morning. They girded our lives. More than anything, they taught us that we were beautifully and wonderfully made in the image of God, and because of that we should respect ourselves and everyone else we encountered. They made us believe that our humanity held a divine spark.

With the exception of some regional details, this is utterly familiar territory for me. It could serve as a description of my own family and our life within a white evangelical church and private school up through the election and re-election of Ronald Reagan.

But then — imperceptibly at first, but rapidly — things changed:

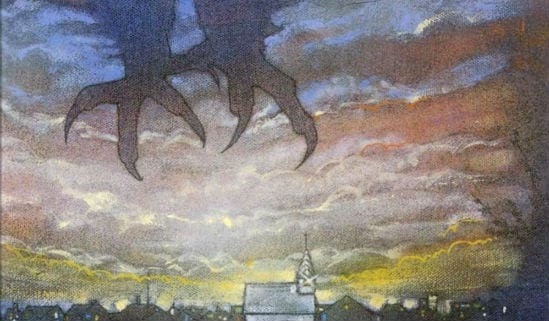

I’m not sure exactly when my family got the idea that we were at war with larger American culture. But I know that at some point our lessons about God’s love became peppered with the idea that we were engaged in spiritual warfare, inhabiting a world where dark forces were constantly attempting to sever us from the will of God. The devil was real, and he was at work through “gay” Teletubbies and pagan Smurfs, through Dungeons & Dragons, through the horrors of MTV. At one point, my parents forbade TV altogether, and disconnected the stereo system in my car. We still loved Uncle Robert, but believed that the AIDS he’d contracted was a plague sent by God, just as we believed that abortion was our national sin, for which the country would likewise be held accountable. We awaited the Rapture, when Christians would be spirited away and Jesus would return to deal (violently) with the mess humans had made of things. Over time, and even before the introduction of Fox News, whatever nuance we might have seen in the culture evaporated into a stark polarity.

It sounds like Morris’ family read a bit more Frank Peretti than mine did, but it didn’t matter that our church avoided the more Pentecostal/charismatic version of “spiritual warfare.” My family, like hers, was conscripted into an army fighting a spiritual war against the devil himself and against all of his infernal servants — which is to say, against tens of millions of our otherwise ordinary-seeming neighbors.*

We didn’t yet think of all those neighbors as demonic back during the 1980 election. We rallied behind Ronald Reagan in that election in opposition to a different great enemy — the Communist empire of the Soviet Union. The Russkies were the real enemy then and we couldn’t afford to be weak, giving away canals and championing human rights and refusing to nuke countries that took our people hostage. White evangelicals were mostly partisan Republicans in 1980, but because we were Cold Warriors, not culture warriors.

Which is to say, really, that we were partisan Republicans because of our opposition to the Civil Rights Movement who were, in 1980, still using the Cold War as our more-respectable-seeming proxy for losing that political, cultural, legal, moral, and theological argument. We had not yet become partisan Republicans because of our opposition to the Civil Rights Movement who were, by the late 1980s, using culture-war issues of abortion and gay rights as our more-respectable-seeming proxy for losing that political, cultural, legal, moral, and theological argument.

Again, those of us who grew up in this world remember this shift. We lived through it. But you needn’t take my word for it, or Alex Morris’ either. There’s an extensive print record of what white evangelicals were saying during the early 1980s. Let me highlight one stark example, the 1981 manifesto “Christianity and Democracy,” written by Richard John Neuhaus as the founding document for the conservative Institute on Religion & Democracy. That manifesto — written to rally white evangelical support for Reaganism — never mentions abortion or feminism or gay rights. Those issues are nowhere on its radar. They are not lesser concerns, but rather not matters of concern at all.

But that changed during Reagan’s time in office. It changed partly because hardline Cold War rhetoric grew less effective after Reagan himself started hanging out with Gorbachev and asking his Soviet friend if he’d seen The Day After and The Day the Earth Stood Still.

But mainly it changed, I think, because there was so much more money to be made as culture warriors. One big nuclear superpower enemy just wasn’t as lucrative as millions of ordinary-seeming yet demonic enemies living right next door.

As Morris writes, this shift to a culture-war framework was by design:

It created a powerful us-versus-them mentality that mobilized the Christian base fiscally and politically. We were Christian soldiers, and the weapons we had were our votes and our tithes. “The persecution trope is a hell of a fundraising pitch,” says Charles Marsh, a professor of religious studies at the University of Virginia. “For evangelical activists and leaders, many of whom run nonprofits or rely on charitable contributions, that is the most direct and successful way to captivate conservative Christians.”

The wedge issues created during the culture wars of the Eighties and Nineties were thus not matters of equality and social justice or anything that might evoke the liberalism of the Social Gospel (though Jesus spoke on such matters abundantly). Rather they were divisive, pushing the Republican Party further to the right and exacerbating Christians’ sense of being a people apart.

The culture war was just as effective as the Cold War had been for ensuring that white evangelicals were lockstep Republican voters, but it was much more effective as a direct-mail fundraising bonanza for an explosion of religious right organizations and “ministries.”

It was also far more effective at focusing white evangelical political engagement on the root concern of the movement: Overturning that massive political, cultural, legal, moral, and theological defeat suffered during the Civil Rights Movement. After all, enlisting white evangelicals as loyal Cold Warriors might help ensure massive increases in military spending, but that wouldn’t necessarily bring us any closer to, say, erasing the Voting Rights Act. Reversing the strides toward equality achieved by the Civil Rights Movement would require either a total rewriting of the Constitution or else a transformation of the judiciary, stocking the bench with judges whose radical reinterpretations of it would amount to the same thing.

The shift from Cold War to culture war made such a transformation seem possible. And, indeed, it has worked just as intended — with a majority of culture-warrior Supreme Court justices finally, in 2013, succeeding in reimagining the Constitution so radically that the Voting Rights Act would no longer be enforced.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

* I’m not referring here to the Satanic Panic of the 1980s. That was a symptom, not the disease. The fever-dreams of a secret conspiracy of black-robed Satan-worshippers were just the inevitable byproduct of what we had begun to be taught in our churches: Our neighbors were evil people who killed babies and we had to stop them from killing babies because they were evil and baby-killers. Accepting such a slanderous witness borne against our neighbors — millions of our neighbors, but especially all of the women — required a massive leap of imagination. Most of us aren’t capable of imagining such horrors on our own, so we reached for the nearest pop-cultural expressions of such a thing and began looking for B-movie Satanists under the bed.

The Satanic Panic never really ended. We just got used to it. Nowadays we can speak matter-of-factly about the same vast conspiracy of baby-killing neighbors without freaking out so much at the idea of it. We’re simply concerned, we say, with “protecting the unborn.” You know, protecting unborn babies from the immediate threat posed to them by the women carrying them — the presumed evil, presumed baby-killing women carrying them. Those evil, baby-killing women can’t be trusted and those evil, baby-killing women must be stopped, we say with a practiced nonchalance. We have come to “believe” that millions of our ordinary seeming neighbors are demonic baby-killing killers of babies, but we’ve learned how to “believe” such an unbelievable thing without any longer requiring all the gothic set decoration we did back when we were first getting used to the idea.