The first thing to go was the masks. This was in January, well before most of us were paying much attention to the news of a new SARS-type outbreak in some city on the other side of the world.

Before January, we carried a lot of masks at the Big Box — dust masks for drywall work, high-end N95 masks and respirators for painters, and a wide array of face shields and masks in the PPE section over in hardware. We stocked masks and face shields in my garden department, too, along with the chaps and gloves and goggles accompanying the chainsaw displays.

By early February, the masks were all gone and our suppliers couldn’t tell us when we might get more in. We all got good at apologizing to the painters and other contractors who needed masks for their work, but we still hadn’t grasped the meaning of the early warning sign we were seeing.

That’s somewhat forgivable, since it’s not easy to see what’s coming when what’s coming is unprecedented. Plus we were all under the spell of the weird complacency that follows successful efforts to stamp out epidemics — certain this had to be no big deal for us just like SARS and H1N1 and ebola had turned out to be no big deal for us (thanks to massive, heroic efforts by people we’d never properly thanked). That’s how these things go — any reaction that works will, because it worked, seem like it was an overreaction. And so we’re lulled into the dangerous misconception that the folks “overreacting” the next time are just “overreacting” again, like they always have before.

But there was also an uglier reason we were slower on the uptake than we might otherwise have been. See, the customers buying up all those masks back in January were mostly East Asian. Or, as more than one of my co-workers put it, “them.” “They’re freaking out and buying all the masks.” “They’re buying masks to send home to their families,” it was assumed (you know, because Chester County, America, couldn’t possibly be their real home).

I talked to one customer who was hoping to do that, although we were already out of masks by that point. She had relatives in China and she was worried about them. But to be harshly honest, that family connection wasn’t the only reason she was worried weeks before I was. It was also because news of distant suffering for Chinese people was more real and more significant for her than it was for me. This was partly a function of geographical distance, but also a failure to identify with people I’ve been conditioned to think of as “other.” If I’d better heeded the words of scripture — “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly” — I’d have done a better job of realizing far sooner what was happening.

Disposable gloves, Lysol, and disinfectant wipes went next. We’ve always carried Lysol in the cleaning aisle. It’s never been a huge seller, despite our vendors’ best attempts at aggressive marketing. We’d always get wingstack displays of “waterfall” and “linen” scented Lysol for big sales events — cardboard displays that would fall apart long before even half of the aerosol cans had sold. Then there was the lead balloon of Lysol’s “MaxCover” sprays — a product that, for whatever reason, nobody ever seemed to want. I’d had a pallet of the stuff collecting dust in my overheads for years. This was a product I’d joked we’d be stuck with unless we did a “10 free cans with any purchase” promotion.

By Valentine’s Day it was all gone.

This was getting weird, but it was otherwise still pretty much business as usual. A bit more conscientious hand-washing perhaps, but still mostly just February at the Big Box and the annual frantic preparation for the coming chaos of spring.

Then the quarantine orders and stay-at-home policies started. Not here yet, but the dawning reality of that possibility wiped out our paper goods. Toilet paper, paper towels, all gone with no more coming.

And then, in March, it was here. Most businesses and restaurants were closed. Many of the contractors who provide the backbone of our business were suddenly idled. But we were deemed an “essential” and “life-sustaining” business, and so we were staying open.

That first week was really disturbing. The place was packed. We’re in a relatively affluent area and it seemed like all of the people who suddenly found they didn’t have to go to the office decided to go shopping instead, heading out to the only stores that were still open. We had little paper badges we pinned on our aprons, politely asking customers to respect a 6-foot social distancing from us and from one another, but in that first week almost nobody was respecting that. (We asked if we’d be allowed to wear badges that instead read “Step the #@$% back.” But no.)

We sold out of paint that first week. It seemed that people suddenly stuck at home staring at their walls decided it’d be the perfect time to change the color of those walls, and so our paint desk and our paint associates got mobbed. They built a kind of fort or buffer zone out of those famous five-gallon plastic buckets we sell — four high and three deep all the way around the counter where customers pressed up against one another, leaning in over each other over the buckets. It was bonkers. Like something out of a George Romero zombie movie.

Gradually — too gradually, perhaps — we’ve adapted to a somewhat safer mode of operation during this pandemic. We’ve cut back the hours during which we’re open and imposed a 100-customer limit on the building. There’s a designated entry door and another designated exit, with an associate standing by each counting customers in and out. When the store is at capacity, a line stretches out into the parking lot, with customers spaced out by painted lines every six feet.

Everybody has to wear a mask now, even though actual masks are still hard to come by. So we’re seeing lots of bandanas, scarves, and some remarkably ingenious homemade creations. The company finally got ahold of enough masks to supply them for associates, but when we get the very rare occasional shipment of the masks we used to carry for sale they now get donated to local hospitals and long-term care facilities (along with whatever disposable gloves we get).

Big plexi-glass shields went up around all of our checkout counters and service desks last weekend, including the paint desk (where the great wall ‘o buckets still stands). All of this seems — mostly — to provide a strong enough visual reminder to do what those polite apron-badges couldn’t do, so the majority of customers are now scrupulously respectful of social distancing. Close-talkers, alas, still remain hopelessly unaware that they are close-talkers. And we get our share of Fox-addled customers infuriated by the inconvenience of all our new precautions against what they angrily insist is a “hoax.”

Mostly, though, just like the local supermarkets, we’re gradually figuring out and implementing the safest ways to continue the inherently unsafe business of retail in a pandemic.

My cleaning aisle is a disgrace. If it had looked like this six months ago, I’d have fired myself. We’ve got degreasers and some laundry soaps and floor polish and not much else. Anything remotely disinfectant is gone by lunchtime on the day it’s received. Bleach? Haha, good one, no.

We don’t bother stocking the paper goods shelves anymore. When we get a shipment of toilet paper or paper towels, we just jack the whole pallet up next to the entrance, hang a sign that says “Limit 2 per customer” and soon thereafter take the empty pallet back to receiving.* The shelves where we used to carry those paper goods are now haphazardly stocked with whatever random cleaning supplies our buyers can get their hands on. It looks like a cross between an Aldi and a garage sale.

The biggest change now is that a much larger share of our total business is BOPIS — buy online, pick up in store. (I have long argued that this should be BOPUIS, and pronounced with a fancy French accent, but this never caught on.) “Pick up in store” now means picking it up outside the store — curbside pick-up without leaving your car.

This is a Good Thing. It involves fewer people in the building and a lot less interaction between customers and associates. But it’s also a new way of doing things. We’re physically set up and staffed as a store, not as a fulfillment warehouse, so we’re still figuring out what it means to have more — and eventually most — of our business work this way instead, at least for the foreseeable future. (How’s that massive rapid-testing, infection-tracing system, and vaccine coming? Still nowhere near a top federal priority? OK, then.)

Personally, I vastly prefer serving customers in a line of cars outside to continuing to have 2,000 people from all over coming through the building every day. We’re still working in unavoidably close proximity to one another — more than 100 associates working here throughout a given week — but it at least slightly reduces the number of people we’re exposed to and/or exposing to us.

Going to and from this hive of activity every day is cause for some anxiety. Here at home, I’m allegedly “quarantined” with three other people. My wife has been going a little stir crazy since the salon she works at closed its doors more than a month ago. Younger daughter is still in grad school, but all of her classes for this semester were online anyway. The boyfriend (who’s now quarantining here with us) is still working, but he’s got a fire-watch gig with a security firm that involves sitting in his car without interacting with anyone else. Apart from occasional trips to the grocery store, they’d all be completely safe from exposure to this virus — if not for me.

With me living here, going to and from the Big Box where everybody from everywhere is still rubbing shoulders every day, I feel like I’m endangering the people I live with. That’s not cool. We’re getting a small (and fiercely conditional) hazard-pay bonus, and they’ve upped OT pay, but that doesn’t erase the anxiety we’re all feeling about our families and our co-workers.

Like Nancy, for instance. She’s my plant lady. She looks exactly like the retired librarian that she is and she knows more about the flowers and herbs and vegetables we have for sale than the folks from the nursery that supplies them. Or Frank, the 80-something guy who’s worked in the electrical department forever, shrugged off cancer and a stroke, and still packs down more stock than most people half his age. I’m very fond of both of them, and very worried every time I see them in the building.

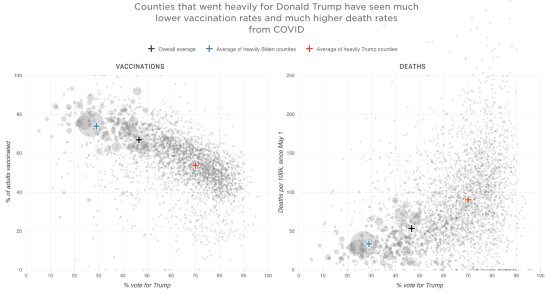

Or think of any of the other grizzled old semi-retirees we’ve got working in our store. Many of them are Fox-addled old right-wingers convinced by their non-news news diets that this is all just an over-hyped flu being blown out of proportion to make their favorite president look bad, but that doesn’t keep me from being horribly worried about all of them. (Workers 65-and-up are getting a small additional bonus, but that feels a bit like one of those Colonial Penn policies to cover funeral expenses.)

Chester County, so far, hasn’t been nearly as hard hit as Philadelphia or the other four surrounding counties, or as Lancaster County next door. But we’ve had 950 confirmed cases and 67 deaths. Our county coroner’s office is already overwhelmed and the National Guard had to be called in to assist at our VA hospital, where at least 10 people have died already.

That’s the context in which my co-workers and I are gathering every day to perform the “essential” and “life-sustaining” work of making sure everybody in Chester County has thick, green lawns with immaculately mulched flower beds.

Because pandemic or no pandemic, spring has hit at the Big Box and that’s what spring means there every year: a frantic race to keep customers supplied with more mulch and grass seed and RoundUp and 31 flavors of garden soil than you would believe.

With every pallet of mulch or topsoil I sell and replace, I’m reminded of this passage from Ed Yong’s Atlantic article “How the Pandemic Will End“:

Think of it this way: There are now only two groups of Americans. Group A includes everyone involved in the medical response, whether that’s treating patients, running tests, or manufacturing supplies. Group B includes everyone else, and their job is to buy Group A more time. Group B must now “flatten the curve” by physically isolating themselves from other people to cut off chains of transmission.

That wasn’t entirely accurate. For isolation to work, we also require a Group C — the farmers, grocery workers, gas station attendants, bus drivers, sanitation workers, etc., without whose continuing work it wouldn’t be possible for everyone else in Group B to isolate themselves and stay the eff at home. A lot of what we do at the Big Box legitimately falls under that category. We’re a huge warehouse full of all kinds of things people need to keep their homes livable — plumbing and electrical repairs, lightbulbs, batteries, mousetraps, and all the literal nuts & bolts it takes to keep a household held together. “For want of a nail,” as the proverb says, and we’re where you go for nails.

But the Big Box isn’t just a hardware store, it’s also a “home improvement center.”** That “home improvement” business is what lets us make all the necessity-driven hardware side of things so affordable. There’s a ton of stuff we sell — and are now busily selling — that is not in any way essential or life-sustaining or otherwise justifiable for us to be enticing Group B to fail at their job of staying home to come out and buy.

One could argue, on the other hand, that since we’re already open — already putting our associates and customers at risk to provide necessities, we might as well continue supplying them with the niceties too. Isolation and quarantine doesn’t have to be austere and unpleasant for it to be effective. Just like the supermarkets are still open not just for milk, but for chocolate milk too, why shouldn’t we continue selling unnecessary, discretionary things like mulch and grass seed? And doesn’t it make it easier to maintain this isolation, make it more likely that people will mostly stay home, if they’re at least able to buy what they need to tackle those projects around the house they’ve suddenly got time to do? Maybe that new patio furniture set I sold yesterday will be the thing that makes quarantine bearable for the folks who bought it and therefore the thing that keeps them at home where they need to be during the weeks or months ahead?

That, I suppose, is the reasoning behind why we’re still open to the public for 12 hours a day. (Well, that and whatever kickbacks the consistently anti-worker and anti-consumer retail lobby is paying to make sure that reasoning prevails.)

And that, I suppose, is what those of us in Group C should be telling ourselves as we put our health and our families at risk in order to make it more possible and more likely that Group B will (otherwise) keep up their end of the bargain.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* Pro-tip: Most Big Box stores have overnight freight teams that work Monday through Friday. That means new product hits the shelves in the mornings Tuesday through Saturday. If you’re looking for toilet paper — or, if you’re really hoping to get lucky, disinfecting wipes — your best bet is to check early mornings on any of those days. Unlike groceries, supermarkets, and pharmacies, we don’t yet have designated early morning hours for seniors and other at-risk customers. But call ahead first.

By the way, just to see what would happen, I stuck one of those “Limit 2 per customer” signs on a display of otherwise normal-selling laundry detergent. It was gone by the next day. Fascinating.

** If the difference between “hardware store” and “home improvement center” sounds like the difference between “local church” and “mega-church,” that’s because it is.