A while back I changed my Twitter handle to “The 1611 Project.” So let me explain that.

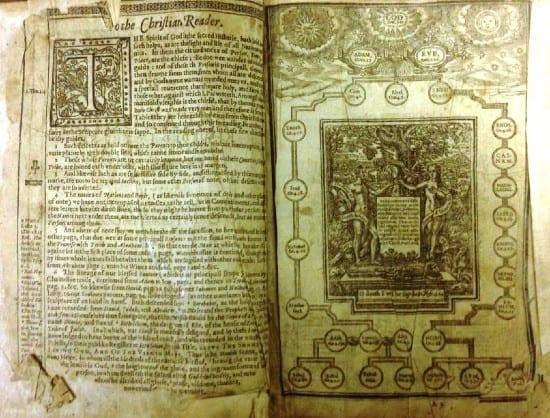

For those who didn’t grow up in white fundamentalist American churches, 1611 is a Big Date for white Christians because it marked the publication of the KJV — the authorized and official King James Version of the Bible.

The KJV wasn’t the first English translation of the Bible, or even the first such translation approved by the English-speaking church. But it would become the first mass-produced English translation, the version of the Bible that would make white Bible Christianity possible.

Bible Christianity — what eventually became “evangelicalism” — did not exist for most of Christian history. It hadn’t yet been possible for it to exist. Evangelical Christianity is proudly “Bible-based,” and that wasn’t something it was possible to be without readable Bibles in the hands of ordinary laypeople. The mass-production and mass-consumption of the KJV is what made English-speaking evangelicalism a possibility. Such a thing could not exist before the availability of a readable, affordable, accessible Bible in every Christian home. The possibility of its existence began in 1611.

Here was a new thing. English-speaking Christians now had the opportunity to read the Bible for themselves, on their own, unmediated by liturgy or clergy. This was not something they would be able to learn to do from prior generations of Christians. It was something they were going to have to figure out how to do on their own, over the coming generations, in the context of those generations.

Which brings us to the “Project” part of “The 1611 Project.” That’s a reference to The New York Times’ ambitious “1619 Project,” which explores how the history and culture of the United States was shaped by — and continues to be shaped by — slavery:

In August of 1619, a ship appeared on this horizon, near Point Comfort, a coastal port in the English colony of Virginia. It carried more than 20 enslaved Africans, who were sold to the colonists. No aspect of the country that would be formed here has been untouched by the years of slavery that followed. On the 400th anniversary of this fateful moment, it is finally time to tell our story truthfully.

And no aspect of the Christianity that would be formed here has been untouched by the years of slavery that followed. That Christianity took shape thanks to those two things that had suddenly become available in every Christian home in the English colonies of the New World: Bibles and slaves. 1611 and 1619.

There’s been a great deal written about how the presence of those Bibles shaped those English-speaking Christians’ attitudes toward slavery, but far less about how the practice of enslaving others shaped the way those English-speaking Christians taught themselves to read, study, and interpret those Bibles.

Consider, for example, historian Mark Noll’s excellent book on The Civil War as a Theological Crisis. It’s a really good book, offering a wide-ranging and insightful survey the full spectrum of ways that early 19th-century white Christians understood what “the Bible says” about slavery. But that antebellum 19th-century focus is also too late — 200 years too late. It skips over the most important aspect of this “theological crisis” — the centuries in which the practice and rationalization of slavery taught English-speaking white Christians how to read and interpret the Bible.

This is where the “evangelical” or “Bible Christian” hermeneutic comes from. Everything we take for granted about white evangelical hermeneutics was shaped by the defense of slavery — the clobber-texting literalism, chapter-and-verse concordance-ism, even the faux-naive pretense that it isn’t even a “hermeneutic” at all because such a fancy-sounding term isn’t necessary for good-hearted good people reading their own Bibles for their own selves. It was — and still is — a hermeneutic designed to bless blasphemy and sin.

Acknowledging that is a necessary step for any attempt to separate evangelical Christianity from its pervasively intrinsic white supremacy. And that is only the first step before beginning the much longer, harder task of re-learning to read those Bibles we suddenly got our hands on back in 1611.

I’m not convinced that American white evangelicals will ever be willing or capable to take such steps. But there’s a sliver of hope in the current ferocity of their attacks on “critical race theory,” which is never accurately described, yet widely condemned as the bogeyman du jour for “conservative” white evangelicals. See, for example, Jemar Tisby’s summary of such condemnations in his fine post: “Southern Baptist seminary presidents reaffirm their commitment to whiteness.” These Southern Baptists would say that their main concern here is the “defense of scripture,” which in their minds requires a defense of whiteness because they’re at least dimly aware that their peculiar way of reading and interpreting the Bible is inextricably linked to that whiteness, that they cannot secure the one without defending the other.

While this dim awareness remains unexplored and has not been consciously acknowledged, their attacks on whatever it is they imagine “critical race theory” to be are making the link between their hermeneutic and their whiteness increasingly obvious and explicit. Perhaps it will eventually become obvious and explicit enough that even they will come to understand what it is that they’re saying. Should that time ever come, they’ll have some consequential choices to make.