(Isaiah did not really convert Israelites to secularism. The title references this.)

One of my favorite passages in the Bible comes from the no-holds-barred opening chapter of Isaiah, verse 12. This is, the prophet Isaiah says, the voice of God speaking. And God is asking a question: “When you come to appear before me, who has asked this of you, this trampling of my courts?”

I suppose that’s a rhetorical question because God doesn’t wait for an answer. God just keeps going, exasperated with all of the pious busyness that has taxed the infinite patience of the Almighty: “Your sacrifices … your incense … your worthless assemblies … your appointed festivals … your prayers.” All of these things are getting on God’s last nerve. “They have become a burden to me,” God says. “I am weary of bearing them.”

Every one of the things God lists here is an act of worship. And every one of these acts of worship was commanded by God.

“Who has asked this of you?” God asks. Who asked you to do any of this?

That’s an astonishing question because the answer, undeniably, is You did. Every single one of these things was something that God asked and commanded God’s people to do. Each one is an explicitly God-given religious duty.

And yet, Isaiah says, God can no longer abide the people doing what God asked them to do. Because, as Isaiah says — or as Isaiah says that God says — those same people’s hands are “full of blood.” All of that divinely established religious worship is contemptible without justice:

When you spread out your hands in prayer,

I hide my eyes from you;

even when you offer many prayers,

I am not listening.

Your hands are full of blood!

Wash and make yourselves clean.

Take your evil deeds out of my sight;

stop doing wrong.

Learn to do right; seek justice.

Defend the oppressed.

Take up the cause of the fatherless;

plead the case of the widow.

That’s Isaiah chapter 1, but Isaiah is far from done with this theme. Here’s a similar passage from Isaiah 58, where again the prophet tells us this is the voice of God speaking — the voice of God condemning the very same religious duties that the very same voice of God had previously commanded:

Day after day they seek me out;

they seem eager to know my ways,

as if they were a nation that does what is right

and has not forsaken the commands of its God.

They ask me for just decisions

and seem eager for God to come near them.

“Why have we fasted,” they say,

“and you have not seen it?

Why have we humbled ourselves,

and you have not noticed?”

Yet on the day of your fasting, you do as you please

and exploit all your workers.

Your fasting ends in quarreling and strife,

and in striking each other with wicked fists.

You cannot fast as you do today

and expect your voice to be heard on high.

Is this the kind of fast I have chosen,

only a day for people to humble themselves?

Is it only for bowing one’s head like a reed

and for lying in sackcloth and ashes?

Is that what you call a fast,

a day acceptable to the Lord?

Is not this the kind of fasting I have chosen:

to loose the chains of injustice

and untie the cords of the yoke,

to set the oppressed free

and break every yoke?

Is it not to share your food with the hungry

and to provide the poor wanderer with shelter—

when you see the naked, to clothe them,

and not to turn away from your own flesh and blood?

Passages like this are bewildering if we try to view them from the framework of what we discussed in the previous post as the geocentric model of normative white Christianity. According to that framework, what we have here is Isaiah and the very voice of actual God urging God’s people to abandon religion entirely, deconverting to an apparently “secular” scheme of social justice. Prayer, worship, and stomping through the doors of a church are all dismissed here as meaningless, wholly insignificant in comparison with the paramount duties God enumerates and describes — all of which seem to be things that white Christianity perceives and portrays as “secular.”

Part of the strangeness here is that Isaiah wouldn’t have understood that distinction between sectarian and “secular” ideas. Nor would any of his/their original readers. But then again I’m not sure that I entirely understand what it’s intended to mean either, because while it initially might seem clear to our modern eyes, it gets a lot fuzzier the more we look.

OK, so we’re supposed to make a ledger, I guess? On one side we put all the explicitly sectarian concerns and practices: prayers, sacrifices, worship services, holy days, fasting, etc. On the other side we put the general, non-sectarian, “secular” ideas and practices that we should assume will be values shared by everyone, even those outside of our sectarian belief systems: justice, equality, civil rights, work without exploitation, freedom from oppression, freedom from slavery, food for the hungry, clothes for the naked, shelter for the homeless, etc.

But none of those things in the sectarian column are actually unique or exclusive to our sect. We may have unique forms of those things, but parallels to them can be found in almost every other religion or sect as well. So we may approach them all from the peculiar perspective of our own sect, but we can’t really claim any of these things as uniquely ours. If anything, such ideas and practices seem more widely and universally held than most of what we’ve listed in the “secular” column.

And just look at that “secular” column. It’s like a utopia. If we’d set out to make a religious/secular distinction that skewed the scales in favor of “secularism,” we couldn’t have come up with a better set of lists. If this is what “secularization” looks like, then somebody’s gonna have to do a much better job of explaining why it’s something we should lament instead of celebrate.

Lamentably, everything in that “secular” column seems too rare in practice for us to regard any of it as a set of universal values that transcends all sectarian boundaries. Maybe those things are universal aspirations — ideals valued in the abstract by all rational people everywhere, but tangible examples of their actual existence are far rarer, it seems, than examples of prayer, worship, or holy days.

Getting back to Isaiah, though, he couldn’t have imagined the kind of thinking that would lead us to make such a two-column ledger. The very idea is part of what he’s railing against — and what he reports God as railing against, the idea that there is some meaningful category of piety or religion that could exist apart from the pursuit and practice of justice.

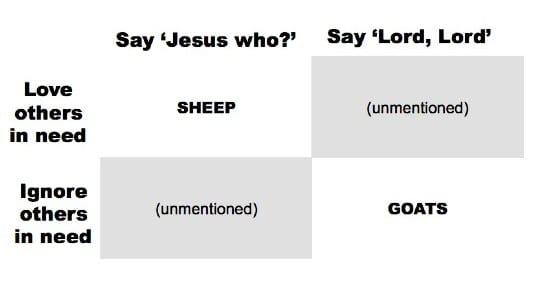

I appreciate that such a category exists in theory, because we have two variables here — prayer/piety and justice/liberation. And whenever you’ve got two variables, you have at least four theoretical categories. But just because such categories all exist in theory doesn’t mean they’re actually real. They could be like a milk chocolate Mounds bar or a dark chocolate Almond Joy. Or — as the two-column table above indicates — they could be like the religious sheep or the unjust goats, two theoretical categories we leap to imagine but which are utterly, unsettlingly absent from Jesus’ parable.

We’re so convinced of the reality — of the priority — of those two theoretical categories that many Christians who’ve read that parable in Matthew 25 are surprised by the suggestion that they have no part in Jesus’ story. Go ahead and read it again. They’re not there. Jesus presents his final word on the final judgment and portrays it as one that includes two and only two categories. The first category, the “goats” — the damned, the doomed, the unsaved and eternally condemned — is the group that looks at Jesus and says, “Lord, Lord.” The second and only other category is the “sheep” — the saved, the forgiven, the just, the eternally blessed — and everyone in that group looks at Jesus and has no idea who this guy is.

That’s so disturbing that we block it out, constructing whole systematic theologies that almost completely ignore the two categories Jesus actually mentions while prioritizing and preoccupying our thoughts with the two theoretical, merely imaginary categories that he never even acknowledges. And as for the other variable mentioned in Jesus’ parable — the more important variable separating the sheep from the goats — we consign that to some supposedly “secular” realm, separate from and irrelevant to whatever it is we choose to mean by “salvation.”

Even though Isaiah and the voice of God in Isaiah never mention it, I would guess that the people of God they call for — the ones who seek justice, defend the oppressed, loose the chains of injustice, break every yoke, etc. — might also pray and offer tithes and gather for worship without God finding such things wearisome and exasperating. But Isaiah and the voice of God in Isaiah, like Jesus, clearly view “justice” as a “weightier matter.” Unlike Isaiah/Isaiah’s God, Jesus even gives us permission to also pursue such lesser forms of religion, but only if we first attend to justice.