I usually like Vox’s “explainer” pieces. I could have used one today to explain why Vox thinks we all need to read “James Carville on the state of Democratic politics.”

Alas, I need to respond to the Headline Chasin’ Cajun here because of this bit:

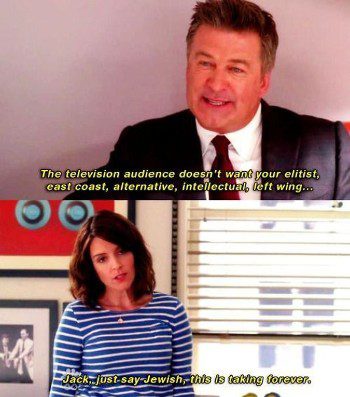

James Carville: Honestly, if we’re just talking about Biden, it’s very difficult to find something to complain about. And to me his biggest attribute is that he’s not into “faculty lounge” politics.

Sean Illing: “Faculty lounge” politics?

Carville: You ever get the sense that people in faculty lounges in fancy colleges use a different language than ordinary people? They come up with a word like “Latinx” that no one else uses. Or they use a phrase like “communities of color.” I don’t know anyone who speaks like that. I don’t know anyone who lives in a “community of color.” I know lots of white and Black and brown people and they all live in … neighborhoods.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with these phrases. But this is not how people talk. This is not how voters talk. And doing it anyway is a signal that you’re talking one language and the people you want to vote for you are speaking another language. This stuff is harmless in one sense, but in another sense it’s not.

Illing: Is the problem the language or the fact that there are lots of voters who just don’t want to hear about race and racial injustice?

Carville: We have to talk about race. We should talk about racial injustice. What I’m saying is, we need to do it without using jargon-y language that’s unrecognizable to most people — including most Black people, by the way — because it signals that you’re trying to talk around them. This “too cool for school” shit doesn’t work, and we have to stop it.

I wholly agree that we should avoid “using jargon-y language that’s unrecognizable to most people.” Which is why I think it’s ironic that Carville himself immediately transitions into doing exactly that by ranting against “wokeness.”

What does that jargon — that bit of “fancy” college talk — mean here? I don’t know. Most “ordinary people” don’t know.

And James Carville very clearly doesn’t know either. He did not choose this word to express some meaning, but instead has simply thrown open his mind and let the ready-made phrases come crowding in. “They will construct your sentences for you – even think your thoughts for you, to a certain extent – and at need they will perform the important service of partially concealing your meaning even from yourself.”

And James Carville very clearly doesn’t know either. He did not choose this word to express some meaning, but instead has simply thrown open his mind and let the ready-made phrases come crowding in. “They will construct your sentences for you – even think your thoughts for you, to a certain extent – and at need they will perform the important service of partially concealing your meaning even from yourself.”

My guess is that Carville is using “wokeness” as a rough synonym for what those in his 20th-century called “political correctness,” which is to say as a self-flattering, dismissive evasion-by-caricature of anything that a cranky old man hasn’t yet bothered to understand.

In any case, though, Carville’s invocation of “wokeness” is undeniably jargon — language used only by and within the close-knit guild of punditry and not language used, preferred, or understood by the vast majority of “ordinary people” outside of that guild. Sometimes the jargon of guilds conveys layers of complex meaning that non-experts would struggle to grasp, but sometimes — as is the case here — it conveys no meaning other than one’s exclusive membership in that exclusive guild.

What I most need to address here, though, is Carville’s use of the phrase “faculty lounge” — a phrase I’ve also used quite a bit to mean something very different from what he apparently means by it.

Carville speaks of “faculty lounge politics” as a form of sneering elitism that uses opaque language that most normal people would find off-putting and confusing. But I adopted that phrase because I admire professors and scholars — admire that they have dedicated themselves to learning and knowing things that others often don’t know.

Here’s how I described this back in 2013:

The faculty lounge is a place where teachers and professors can relax and talk amongst themselves without worrying about who might be listening in. I think that also describes the role that Books & Culture has played in American evangelicalism. … It was a place where scholars could engage one another, writing long or writing deep in a way that the general-public format of Christianity Today did not allow.

But Books & Culture also, from the outset, was a forum for something else that popular evangelical publications did not allow: candid, unapologetic discussion of taboo knowledge and subject matter that had to be tip-toed around delicately when writing for a wider evangelical audience. If you are an evangelical scholar writing for Christianity Today, there are a host of Things That Cannot Be Said without sparking a heated controversy — even though none of them is actually controversial even among very conservative evangelical scholars. Whether the topic is the authorship of the pastoral epistles, or the archaeological evidence for (i.e., against) the conquest of Canaan, or more secular subjects such as the age of the Earth, Books & Culture allowed evangelicals to discuss what we’re learning honestly and openly without having to worry about setting off the hair-pin trigger alarms of either the culture warriors or the inerrantists patrolling the pages of CT for anything they perceived to be a deviation from their factually challenged version of God’s Own Truth.

See also this 2017 post, which uses the latest N.T. Wright book on Paul to get at both the good and the bad aspects of the “evangelical faculty lounge.”

Carville and I agree that “the faculty” need to learn to communicate to laypeople and non-scholars by avoiding “jargon-y language” and “fancy college” talk. But where I’m arguing that those faculty have an obligation to share their knowledge with “ordinary people,” Carville seems to be warning them not to tell those “ordinary people” anything they don’t already know. Or think they know. And certainly not to say anything that those ordinary people wouldn’t want to hear.

Those of us who belong or have belonged to the “evangelical faculty lounge” all know and understand that the universe is 13-14 billion years old. We all read Mark Noll’s The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind and nodded in somber agreement with his dismay at the anti-intellectualism of young-Earth creationists. But when we’re speaking to a more general evangelical audience, we’ve learned to be hesitant to say too much about that lest we get bogged down in conflict and controversy or find ourselves in the crosshairs of the perpetually indignant direct-mail fundraising “ministries” always on the lookout for new scapegoats.

It’s not easy to communicate complex truths to a general audience, and it takes courage when you know that doing so will put a target on your back, but I still contend that it’s the calling of the faculty to teach and thus we are obliged to find ways to speak the same truths to the general public that we speak to one another within the safety and comfort of the faculty lounge.

Carville seems to be using the same phrase — “faculty lounge” — to argue the opposite. He’s not merely urging “the faculty” to learn “to speak the way regular people speak,” but to keep their “metropolitan, over-educated” ideas to themselves. That seems unhelpful.