Mark Evanier notes the big difference between “Elvis is alive” conspiracy theories and COVID-denialism:

We are all familiar with people who stake out positions and say, in effect or for real, “Nothing will ever convince me otherwise.” Back when I was way too interested in the Kennedy Assassination, I ran into them at every turn. J.F.K. was killed by Lizard People from the planet Reptilon and no evidence of any kind could ever convince them otherwise.

Or Man never walked on the Moon or 9/11 was an inside job or Donald Trump really won every state, etc. We’ve all heard these set-in-stone beliefs. But here’s the thing: COVID Denial — it’s a fake disease or it’s nowhere near as bad as they say or it’s all a plot for Mind Control — is the first time people are literally betting their lives. You couldn’t die by believing Elvis is still alive but you could by refusing to take the coronavirus seriously. You and someone close to you could.

That’s a good point, but the words “beliefs” and “believing” call for a lot of unpacking here.

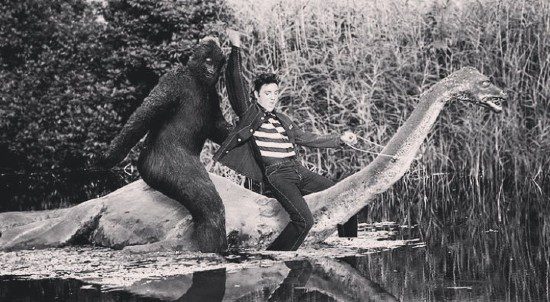

Evanier’s point involves a kind of implicit spectrum of conspiracy theories that’s easy to recognize but hard to describe. Toward one end we have the kind of conspiracy theories that seem relatively harmless and low-stakes for “believers” — Elvis sightings, Bigfoot, cryptozoology, Mothman, some forms of UFO enthusiasm and ghostly phenomenon. It’s possible to “believe” in such things without becoming deeply invested in them. Such belief can be a kind of hobby that doesn’t require any changes in a person’s lifestyle or in their interactions with others. It’s possible to approach such subjects with a kind of carefree “Yeah, could be, why not?” attitude.

Toward the other end of the spectrum things get darker and more paranoid, with “beliefs” that logically entail and demand greater investment and that can be life-altering. This includes QAnon, 9/11 truthers, chemtrails, belief in nefarious 5G effects, Satanic baby-killerism in all its forms, and UFO stuff that focuses more on the terrestrial Men in Black than on the little green men.

I think what distinguishes the two ends of this spectrum is “Them.” You can “believe” in Bigfoot without needing to explain the lack of evidence by positing the existence of a dark and powerful conspiracy shaping all of our lives to cover up and repress the “truth” about elusive ape-men deep in the woods. The paucity of evidence for Bigfoot or the Loch Ness monster can simply be attributed to these creatures being rare and averse to human attention. You don’t need to conclude that the evidence is all being suppressed by Them — by the government and Bill Gates and Harvard and “the media” and all the other nefarious actors who must surely be “in on it.”

“Them” is what makes most conspiracy theories far from harmless. Once you commit to “believing” in Them, you start to see those around you as enemies or collaborators. And it’s always — always, always, always — a very short leap from any form of “Them” to uncoded, explicit antisemitism.

At the less harmful end of the conspiracy theory spectrum, where no Them is required, belief in something like Bigfoot can be an expression of a kind of humility and sense of wonder that are, in some sense, admirable.

“Elvis is still alive” is, like Bigfoot, a “belief” that generally doesn’t require a nefarious Them. For many devotees of this theory, the magical, mystical, inscrutable nature of the King himself is all the explanation required. “Because he’s Elvis” is, for these folks, a sufficient answer to all of the whys and hows of this mystery.

Others, taking a more “realistic” view, suggest that Presley’s faked death and miraculously successful disappearance involved him going into the witness protection program. That variation involves a “them” of secretive government agents, but in this case they’re benevolent, not nefarious. It involves murmurings and whisperings of some vague criminal plot, but the criminals are not still out there, orchestrating their plots and controlling the world. In this scenario, the villains have already been stopped and punished — their schemes foiled by Elvis himself. Long live the King. (It’s kind of Christus Victor, if you think about it.)

UFO enthusiasm can take a similarly benign form. It is possible to believe that we have caught fleeting glimpses of intelligent extraterrestrial visitors who, like Elvis, have purposes of their own, a desire not to have their presence widely proven, and a preternaturally superior ability to avoid detection. Such a belief does not, in itself, require the existence of an evil cabal of Them secretly controlling the world and repressing this forbidden truth.

But even if belief in UFOs* starts there, it tends to head toward the other end of the spectrum, positing a vast and powerful Them standing between good people and the truth. If we “believers” have collected all of this tantalizing “evidence” of these extraterrestrial visitors, why hasn’t the government learned all of this? After all, the government has more resources and better technology. Maybe they already know, far more than we know, and maybe they’re using all of those resources and all of that technology to hide the truth. Maybe they’re in on it — maybe they’re Them. And just that quickly “Wouldn’t it be cool if aliens showed up?” turns into shadow governments run by secret cabals, feverish paranoia, blood libels and Satanic baby-killerism.

I still love The X-Files, but the mythology of that show was squarely far off on the Them side of the conspiracy spectrum of paranoia. That wasn’t because Chris Carter was himself a paranoid conspiracist, but because he recognized that the fantasy world of paranoid conspiracists makes for a more exciting story. It provided a host of villains and antagonists to prove the mettle of our heroes.

And that, I believe, is also what motivates most “belief” in conspiracy theories and pushes them further and further along the spectrum toward the more paranoid, more harmful end. It’s a search for excitement and a way to create villains that will make “believers” seem or feel or pretend to feel like more of a hero.

It’s this need and desire for meaning and excitement, the need to feel like a hero, that accounts for much of the anger, resentment, and hostility that conspiracy theorists demonstrate when they react to evidence that debunks the existence of their longed-for villainous “Them.” This is not the courageous anger of a hero boldly standing up against evil despite overwhelming odds. It is, rather, the whining anger of someone upset that you’re threatening to spoil their game.

And it is a game — a kind of fantasy role-playing game or LARP. QAnon is, essentially, an MMPORG — a massively multiplayer online role-playing game. To participate is not to become a “believer,” but to become a “player.” And no player is ever quite fully able to immerse themselves in the make-pretend reality of the game to such an extent that some part of them is not aware of that.

This, again, is why trying to debunk paranoid conspiracy theories with facts and evidence and logic tends not to work. The game provides an in-game explanation for all of that, dismissing inconvenient facts and evidence as the work of “Them.” But more importantly, all those facts do not and cannot address the deep need for meaning and excitement — or, at least, for a passable imitation of them — that the player first turned to the game to find. They “believe” in the game because, even if they semi-consciously know it’s not real, they believe it’s the closest they’ll ever get to meaning and excitement and being able to think of themselves as heroes.

This is what accounts for the indomitable “Nothing will ever convince me otherwise” aspect of their commitment to pretending to believe in the game. And I fear that even the possibility of catching, spreading, and dying from an undeniably real pandemic virus won’t change that.

They’re stuck in the game, stuck in preferring the game to reality, until and unless we can convince them of some other meaningful source of meaning. They want and need to be heroes. If we’re going to convince them to stop playing games, we have to show them that’s possible here in reality.

That’s why the sermon preached by the Rev. Mojo Nixon here is relevant as more than just a psychobilly joke about Elvis sightings. We’ll never be able to debunk all the bogus claims of Elvis sightings until we first teach people to look inside themselves and realize, as it were, that there’s a little bit of Elvis inside all of us.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mpb4ZAAP6Z4

* As we’ve noted before “belief in UFOs” usually means the opposite of that. It means the belief that one has already identified these otherwise unexplained flying objects, that one already knows what they are, with great certainty. If someone tells you they believe in UFOs, what they usually mean is that they believe in IFOs. And they will often proceed to identify them for you with extravagant precision, going beyond “I think that weird light in the sky may have been an alien spacecraft” to claiming to know which specific aliens were piloting the craft, where they’re from, and what they’re planning.

I think this is part of what the Pentagon was trying to avoid by replacing “UFO” with “UAP,” reasserting that (as-yet) “unidentified” and (as-yet) “unexplained” are the defining aspect of the category. Or maybe that’s just what They want us to think.