Rebecca Onion on “The Fable of the Sick Anti-Vaxxer.” This is a helpful and timely discussion of the kind of approaches and stories that effectively persuade the unpersuaded, and of how and why that’s not always the same kind of approaches/stories that the already persuaded imagine will be effective.

It is, in other words, something for every would-be evangelist or missionary to read and consider.

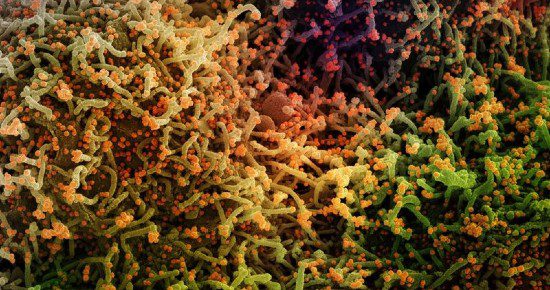

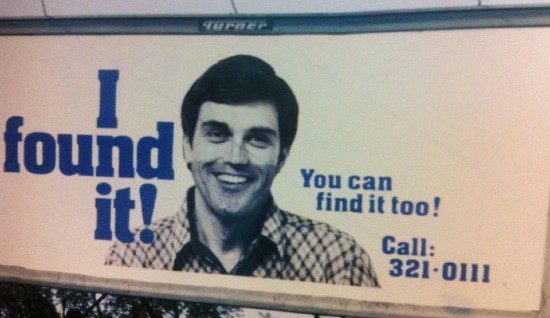

The “Fable of the Sick Anti-Vaxxer” is often a true story — a personal testimony of regret and repentance. “I once was lost, but now am found,” etc. Such stories can be compelling, but they lose their capacity for persuasion when they’re embellished with triumphalism or schadenfreude. Onion cites a folklorist who notes the way theses stories tend to be told and retold less to persuade others than as a way to “cement the in-group of the vaccinated.” Another scholar describes this as a tool for “choice-supportive bias/post-purchase rationalization.”

It’s often employed, in other words, like those religious urban legends about the supposed death-bed conversions of infamous infidels. This in-group high-fiving and trash-talking offers a temporary morale boost for the in-group, but it’s off-putting to everyone else. And it makes even the truest of true stories seem less trustworthy and less convincing. When the in-group deploys real testimonies this way, it makes them seem as dubious as the fundamentalist preacher reassuring his flock that, with his dying breath, Charles Darwin declared that the fundies were right about everything and that he wanted everyone to burn his books and go buy tickets to the Ark Encounter.

The dynamic here — the way that in-group expressions of “choice-supportive bias” prevent and prohibit persuasion of outsiders — will be familiar to anyone who’s participated in certain forms of door-to-door or street evangelism. I’m thinking here of things like “Evangelism Explosion,” or the Fuller-Brush tactics of some Jehovah’s Witnesses, or those unfortunate kids who sign up to be door-knocking fundraisers for PIRG. You can only attempt such approaches for a short while before you begin to realize that their long-shot futility is a feature, not a bug. They’re not designed to bring others into the fold, but to cement and reaffirm your position as a right and righteous insider.

Upon realizing that, of course, you come to a crossroads. You have to decide what is more important to you: Your status as an insider? Or effectively persuading outsiders of what you regard as an urgently necessary truth? Allowing the former to eclipse the latter changes both the meaning of that insider status and the meaning of that urgently necessary truth — the meaning of whatever gospel of salvation it is that you’re promoting.

In-group exercises in “choice-supportive bias,” in other words, can wind up emphasizing opposition to outsiders and can nurture an obsessive concern with boundaries, distinctiveness and separateness and a sense of superiority — all the things that make connection and communication and persuasion all but impossible. (And at the same time, they change the character of in-group members into something less winsome and compelling — something more sulking and self-absorbed, like Jonah or the older brother in Jesus’ version of that story.)

Strengthening in-group bonds has its place, of course, but while “We few, we happy few” was a a great way to fire up his troops to defeat the French in battle, it would have failed miserably if the aim had been to persuade the French.

“Win over” can mean two very different things, but it cannot usually mean them both at the same time.

You can run a very successful marketing campaign based on just the kind of in-group flattery we’re talking about here. Lots of people have made lots of money by carving out a niche as the providers of elite, exclusive, superior and refined products catering to a sub-set of consumers who have the means to indulge in things that will reaffirm their sense of themselves as elite, exclusive, superior and refined.

But that’s why I’m talking about missiology rather than marketing. In missiology, you never want to carve out a niche or skim off a sub-set. You are, by definition, trying to reach everybody because you believe that everybody needs to hear this. This doesn’t mean that every iteration of your message needs to have universal appeal, but it does mean that it should never be exclusive or based on schadenfreude or triumphalistic mockery of others left holding their manhoods cheap, etc.

That’s one reason that vaccination campaigns need to be more like missiology than like marketing. Another reason is that vaccination campaigns aren’t selling something, they’re trying to give something away for free. That can be just as challenging and sometimes even more difficult.

Onion gives the almost-last word to Jonathan Berman, author of Anti-Vaxxers: How to Challenge a Misinformed Movement:

In his book, Berman categorizes anti-anti-vaccination persuasion tactics in three ways: “reactive” (think mean-spirited arguments with anti-vaxxers); “information-deficit” (dumping info on people); and “community-based” (tactics that demonstrate that other people around anti-vaxxers are vaccinating, “taking into consideration their self-identity and values”). These lessons, taken from research done around vaccination drives conducted in service of childhood vaccines, may or may not translate to our current situation. But I think it’s clear that these new fables will only be as useful as we let them. It’s difficult to be kind, when our fragile hopes for some post-pandemic normalcy seem to be falling apart due to other people’s refusal to get vaccinated. But the Fable of the Sick Anti-Vaxxer — a story aimed at the hesitant, from somebody who once thought as they did — may work best when we, the vaccinated, just let it sit, and resist the temptation to gloat.

Berman’s three categories make it clear which approach he prefers as the only one likely to be effective at persuading the unpersuaded. I’ve not read more of his argument than what Onion provides here, but I appreciate the cautious phrasing of “taking into consideration their self-identity and values.” These things must be considered and acknowledged and accounted for. We cannot hope to be heard by anyone, let alone to persuade them, if we don’t bother to figure out who they are and where they’re coming from. We can’t expect them to listen to our stories unless we’re willing to listen to their stories.

But that doesn’t mean that all stories are the same. Some fables are true. Some are not.

Part of “taking into consideration their self-identity and values” includes considering the possibilities that those things may literally be what’s killing them. And when that’s the case, our task is not to reaffirm or to cater to that sense of identity or those values, but to find ways to question them that may convince them to join in that questioning.

This, too, is another difference between missiology and marketing. Marketing is all about identifying and indulging a potential consumer’s identity and values. Missiology is often about challenging them. Sometimes the thing that most needs to be said is this: “Your self-identity and values? They’re killing you. So, yeah, those are gonna have to go.” Or, in other words, “You need a fresh start, a do-over. Ye must be born again.” Olly olly oxen free, etc.