“CNN suspends Chris Cuomo indefinitely,” CNN reports:

CNN has suspended prime time anchor Chris Cuomo “indefinitely, pending further evaluation,” after new documents revealed the cozy and improper nature of his relationship with aides to his brother, former New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo. …

Cuomo’s 9 p.m. program is frequently CNN’s most-watched hour of the day. He is a larger-than-life presence at the network. And he was determined to stay on TV this year despite a flurry of sexual misconduct allegations against his brother, which culminated in the governor’s resignation three months ago.

But new documents released on Monday showed that the veteran journalist was more intimately involved than previously known in shaping his brother’s defense.

“The New York Attorney General’s office released transcripts and exhibits Monday that shed new light on Chris Cuomo’s involvement in his brother’s defense,” a CNN spokesperson said Tuesday evening. “The documents, which we were not privy to before their public release, raise serious questions.”

“When Chris admitted to us that he had offered advice to his brother’s staff, he broke our rules and we acknowledged that publicly,” the spokesperson continued. “But we also appreciated the unique position he was in and understood his need to put family first and job second.”

“However, these documents point to a greater level of involvement in his brother’s efforts than we previously knew,” the spokesperson added. “As a result, we have suspended Chris indefinitely, pending further evaluation.”

It always rankles a bit when cable news channels describe the hosts of their celebrity panel chat shows as journalists, as if staging semi-scripted nightly arguments between opposing political consultants makes you Ida B. Wells or Nelly Bly. CNN calls itself a 24-hour “news channel,” but it’s really a 24-hour op-ed channel which occasionally puts its opinion columnist shows on pause to cover breaking news.

That’s frustrating, because CNN is quite good at covering breaking news. Yet they’ve realized that, most of the time, actual news reporting doesn’t get the ratings that they can get with the celebrity panel chat shows, even though they’re not good at that, and even though those shows are the opposite of a public service. So most of the time CNN is doing the thing they’re not good at instead of the thing they are.

But let’s set that rant aside for another day. The point here is that Chris Cuomo plays a journalist on TV for CNN and it turns out that he has, for the past year, been a dishonest and unethical journalist when it comes to the story of his brother Andrew, the now-former governor of New York. CNN and its viewers trusted Chris Cuomo to report honestly and accurately on stories involving his brother and Chris Cuomo violated that trust.

That’s a terminal offense in journalism. It’s a clean out your desk and go home and find a new line of work offense. And it’s aggravated by the ugliness of Chris Cuomo’s “involvement in his brother’s defense.” He was (allegedly) using his position as a TeeVee Anchor Guy to help aides for his brother collect dirt on and discredit the women who were accusing the former governor of harrassing and bullying them. So this wasn’t just a matter of bias and a failure of journalistic ethics, it was also his cooperation and complicity in the same immoral, disgraceful behavior that ultimately forced his brother out of office.

But still, it was his brother. His actual flesh-and-blood, grew-up-together brother. And so it’s hard to look at Chris Cuomo’s situation without, as that CNN spokesperson said, appreciating “the unique position he was in and … his need to put family first.”

That shaped the reaction to Cuomo’s suspension by most of his (male)* peers in the journalist-ish world of TV panel chat show hosts and guests, op-ed columnists, and blue-check Twitter pundits, most of whom seemed strangely united — across the political spectrum — in responding by saying something like, “I’m not saying what he did was right, but if it was my brother …”

There was an almost boastful tone in many reactions to Cuomo’s quandary, a kind of macho posturing: “What Chris Cuomo did was indefensible, but it was nothing compared to the vile things I’d be willing to do to protect my brother.”

The moral instinct here reminds me of the old joke: “A friend is someone who helps you move. A best friend is someone who helps you move the body.” The moral premise of that joke is not that covering up a murder is good, but that the competing moral claim of loyalty to one’s friend ought to take precedence. It’s better — morally better — to aid and abet murder as an accessory after the fact than it is to be a disloyal friend.

Do we really mean that when we repeat that joke? It’s hard to say. It’s a joke, after all, and what strikes us as funny about it may be the way it exaggerates the obligations of friendship beyond what we understand to be the proper limits of those obligations. Regardless of how funny it is, or why it’s funny, the joke sticks with us because it invites us to consider the clash between competing moral obligations, and that’s the stuff of great storytelling.

This is where real dramatic suspense comes from: the clash of moral obligations. Or, even better, the clash between moral absolutes.

We can be idly entertained, to a degree, by a story in which Our Hero is confronted with a choice between Right and Wrong. But such stories tend to be forgettable and disposable. They linger in our memory only due to their icky residue of flattery. Like all stories, they invite us to ask, “What would I do if confronted with such a choice?” But when that choice is simply between Right and Wrong, the right answer is obvious and cheap and easy, and we come away feeling obvious and cheap and easy for flattering ourselves by providing the only possible answer.

But stories that force Our Hero to choose between Right and Also Right don’t have obvious, cheap, or easy answers. They’re suspenseful because we genuinely don’t know which moral good the hero will choose to honor and which they will choose to deny. And they’re suspenseful because we’re genuinely not sure which moral good we would choose if we were in their shoes. We’re genuinely not sure which moral good we ought to choose. Neither option is obvious, or flattering.

Which brings us to the text for today’s sermon and the song that provides the title for this post, “Highway Patrolman,” from Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska.

Joe Roberts is a good man. That’s the premise of this story, but whether it is or can also be the conclusion of the story is the question here. Joe is a good man, but he’s “got a brother named Frankie, and Frankie ain’t no good.”

Joe loves his brother. That’s good. He is committed to looking out for his brother, to being his brother’s keeper, and that’s good. Joe also probably feels obliged, and maybe a little guilty, because he got a farm deferment in the draft, while his little brother was sent to Vietnam for three years and came back changed for the worse. So we understand, and sympathize, when Joe tells us that sometimes he used his position as a highway patrolman to keep Frankie out of the kind of nickel-and-dime trouble Frankie had a knack for getting into. That’s maybe not so good, but we understand.

For all of the love and the guilt and duty he feels for his brother, Joe still recognizes that there are limits to this obligation. All of those male pundits rushing to affirm Chris Cuomo’s anything-for-my-brother behavior emphasize the “like any brother would” instinct, but they miss the more important part of Joe Roberts’ manly moral creed: “I catch him when he’s straying.” Joe understands that his real duty to his brother is not to help him get out of trouble, but to keep him from getting into it.

The story reaches its crossroads when Joe gets a call involving Frankie and something more serious:

Well, the night was like any other, I got a call ’bout quarter to nine

There was trouble in a roadhouse out on the Michigan line

There was a kid lying on the floor, looking bad, bleeding hard from his head

There was a girl crying at a table, and it was Frank, they said

Now our good man, Joe, is forced to choose between two things he values, between two competing moral claims. Joe is sure that “a man”* must never “turn his back on his family.” But he also knows that he has other obligations and duties — to his job, to his community, to that kid lying on the floor and the girl crying nearby — and that this time he can’t just “look the other way” and cover-up Frankie’s misdeeds.

So what does he do? What can he do? What should he do? What would you do? When those aren’t easy questions, you’ve got a good story. But if you’re dealing with those kind of questions and it’s not in a story, that’s another matter. Dramatic tension and suspense are great stuff in fiction, but in actual life they’re rather unpleasant.

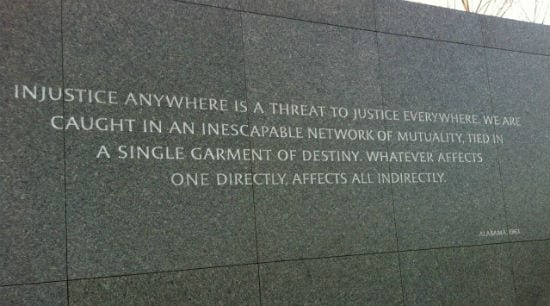

One way to describe the clash of moral obligations confronting Sgt. Joe Roberts (and “journalist” Chris Cuomo) is to consider the complementary principles of solidarity and subsidiarity. Subsidiarity is a fancy word we discuss around here quite a bit. It’s the term in Christian ethical teaching that explores what Martin Luther King Jr. was getting at when he reminded white clergy that “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.” Subsidiarity refers to the ways we differentiate between those direct and indirect obligations of mutuality, helping us navigate and prioritize and particularize what to do and where to act in what might be an otherwise paralyzing and overwhelming sea of obligation.

Subsidiarity, in other words, locates each of us within the vast “network of mutuality.” Joe Roberts’ is Frankie’s brother, and that matters. It shapes and specifies his moral obligations to Frankie, recognizing that this particular direct relationship carries with it direct obligations that are different from what Joe owes to others who are not his brother. Proximity and kinship and personal history impose additional moral obligations and help to define our moral obligations. But they do not bound or limit those obligations. Those obligations are not bounded or limited by proximity or by kinship or by personal history. They are not bounded at all.

Subsidiarity reminds us that we are our brothers’ keepers, but solidarity reminds us that everyone is our brother. Solidarity is universal. Anything less than that isn’t solidarity at all, just a Hobbesian war of all against all — a temporary stage of Hatfields-vs.-McCoys “kinship” that inexorably leads to a lethal game of musical chairs among the surviving kinfolk of whichever clan prevails.

Joe has a brother named Frankie. He also has a brother “lying on the floor, looking bad, bleeding from his head” and a sister crying at a table. A man who opts to help one brother while turning his back on all those other members of his universal family, well, he just ain’t no good.

And if he does that, he ain’t any good even to Frankie. As King reminded us in the verse preceding the ones quoted above, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

We know how the song ends. Five miles from the Canadian border, Joe “pulled over on the side of the highway and watched his taillights disappear.” But what does that mean?

Some take it to mean that Joe is, once again, “looking the other way” and letting Frankie get away. His little brother won’t be arrested, won’t face a trial or a prison sentence. But I don’t think Frankie winds up a free man. He’s been banished, exiled bearing the mark of Cain. He has literally driven himself beyond the boundaries of moral obligation, carrying himself outside of the community of Joe and of Maria and of that bleeding kid, outside of the state and the nation.**

Frankie is gone. And after sitting there for a moment on the side of the highway, Joe will turn his cruiser around and head back home, returning to his particular place in the inescapable network of mutuality and to his role as the keeper of all of his brothers and sisters there.

* I’m discussing all of this in terms of morality, but that’s not quite the same thing as the kind of unspoken moral code that seems to be underlying most of this response to the Cuomos’ situation, which has less to do with morality per se than with some notion of “manliness.” The moral bravado of the claim “I would do anything to protect my brother because that’s what it means to be a good brother” is shared and legitimized by male pundits in a way that the claim “A good sister would do anything to protect her sister” would not be.

The instinctive defense of Chris Cuomo is also gendered in that he was taking his brother’s side against the women his brother had abused. That makes it seem like one of the competing “moral” claims here is the ethical principle of “bros before ho’s” — which is actually neither ethical nor principled at all.

** Sorry, Canada, for casting you in this story as the outer darkness and the realm beyond the bounds of unbounded moral obligation. The universal kinship of solidarity and the universal obligation of the mutuality of subsidiarity really does not and cannot stop at the political constructs of national borders. But the song had to end somewhere and so it ends where Joe’s story ends, not Frankie’s. Joe’s story ends at the border because he is, after all, a highway patrolman. He works for the state.