If you asked ChatGPT to imitate George Will’s baseball writing, the bot might produce something like this sentence: “Baseball is woven into so many of our lives because it is that sphere where childhood dreams play out and lifetime memories are made, where communities come together in triumph and disappointment.”

That’s from David Brooks’ latest column, and it seems even more soul-less and inauthentic in context. It’s s sentence that convinces the reader only that its writer has neither childhood dreams, nor lifetime memories involving baseball, and that the game has never been, in any meaningful way, “woven into” his life.

Fortunately, most of Brooks’ column isn’t about baseball. Unfortunately, the rest of it is even worse — more pretentious, more confused, and less sincere.

Why waste any more time on this habitually disingenuous hack — this second-generation Reader’s Forum shopper and lifelong capicola-eater? Because Brooks’ column is, I think, confused in some helpfully clarifying ways. It is an attempted “Kuyperian” attack against “little platoons.” It’s a criticism of “the politics of spectacle” that is, itself, an example of “the politics of spectacle.” And, above all, it’s a vivid demonstration of one representative Old White Guy’s bewildered failure to understand that 2023 is not 1983, and thus comes across like a boilerplate “shut up and dribble” rant of the sort that Brooks’ predecessors cranked out about Branch Rickey in 1947.

When I was a seminary TA, I had to grade papers on Jim Skillen’s book about the Reformed political theology of Abraham Kuyper. It wasn’t hard to tell which students had read the book and which ones were just riffing based on a loose grasp of the class discussion. Brooks’ column reads like the latter.

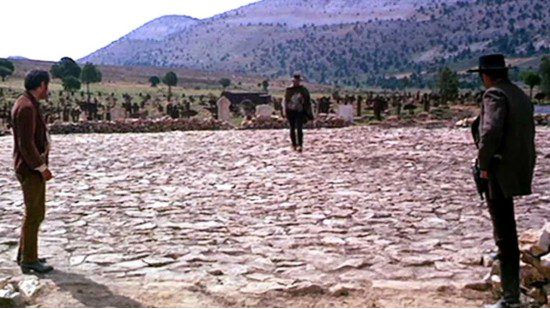

“Sphere sovereignty” was Kuyper’s Protestant/democratic revision of subsidiarity — an attempt to preserve its insights without the hierarchical Great Chain of Being baggage in the original. Brooks enlists this language forgetting that Kuyper’s spheres are distinct, but still “caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.” Brooks seems to think of these spheres as existing in conflict, competition, or tension — as though civic groups, families, and churches were engaged in a tense standoff like the end of The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly.

That’s not how this works. Subsidiarity and/or “sphere sovereignty” are descriptions of and guides to neighborliness, not ground rules for a game of musical chairs. The greatest danger to neighborliness and to justice is not the usurpation Brooks fears — “when one sphere tries to take over another sphere.” The threat to justice, to neighborliness, and to every mutually bound “sphere” of society, rather, is the problem of abdication. When one sphere drops the ball, refusing or failing to meet its responsibilities, the others are forced to step up to do more.

For a real-world example of what that looks like, consider the civic association that is the subject of Brooks’ column and of his scorn: The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence.

The Sisters are a group of drag queens who dress as nuns. Their original habits were the genuine article — donations provided for an all-male production of The Sound of Music by actual Catholic nuns who got the joke. The ad hoc “order” of Sisters sprang from that as a social club — a civic group no different, in pretentious Kuyperian categories, from the Rotarians or the Elks or Masons or Mummers (although their costumes weren’t quite as flamboyant as those of the latter two). They formed a softball team and played against the Gay Men’s Chorus and the Metropolitan Community Church (baseball has been “woven into” the group since its earliest days).

The Sisters were always spectacular, but their early days didn’t involve anything like what Brooks condemns as “the politics of spectacle.” They were certainly political, in the sense that any group that refuses to comply when told they have no right to exist is inherently political. But they didn’t pick that fight and they didn’t start it. And anyone who critiques a politics of resistance without acknowledging the explicit, pre-existing, overwhelming politics it is resisting against is either a fool or a fascist.

What the Sisters mostly did, early on, was Bingo. They hosted Bingo to raise money for community groups and they were good at it because they were funny and fabulous and anyone who isn’t utterly dead inside is bound to have a good time playing charity bingo hosted by a bunch of bawdy drag queens dressed as nuns. This is a time-tested formula that we humans have found fun and funny since the origins of Panto centuries ago.

Things changed for the Sisters when everything changed in the 1980s with the arrival of “gay cancer” and “GRID” and what eventually came to be called AIDS. This is where the abdication of the spheres dragged this social club into a more explicit form of politics.

Look again at Brooks’ list of Kuyperian spheres: “There is the state, the church, the family, the schools, science, business, the trades, etc.” Consider how utterly and thoroughly most of those failed in their duties and responsibilities when confronted with the crisis of the AIDS epidemic. But the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence stepped up, raising their voices, raising attention, raising a ruckus, and raising funds to care for and to fight for people who were being abandoned by their families, churches, and governments.

Which of these do you think was a neighbor? Go and do likewise.

That last bit is from a famous Jesus story about a despised outcast who stepped up when other “spheres” refused to fulfill their neighborly obligations. The care, decency, and responsibility of the Good Samaritan in that story shamed the careless indecency and irresponsibility of the priest and the levite. That shaming was not the Samaritan’s intention, but it was an inevitable consequence of his neighborly action being offset by the background of their callous, indifferent inaction.

How dare an unclean, unholy Samaritan bring shame on distinguished authority figures like a priest and a levite? That, in essence, is Brooks’ complaint in his column. He scolds the Sisters for “narcissism” and for “inflaming hatred,” and for failing to embrace some proper-channel, tone-policed politics of respectability. Brooks begrudgingly acknowledges that the Sisters “provided invaluable services to those in their community, especially during the AIDS crisis,” but every other phrase about them in his column reads like it was written by Anita Bryant in 1983.

Brooks also misunderstands the relationship between the Sisters and, well, the Sisters. He imagines that their attire “dishonors the nuns who live in poverty serving the poor.” And he performs offendedness on behalf of these imagined sisters.

That’s not how that works either. Very broadly speaking, there are two types of Catholic sisters. There’s the kind who put on full habits with wimples so they can protest outside of movie theaters or Dodger Stadium or on EWTN, and then there’s the kind who “live in poverty serving the poor.” The latter group isn’t offended by the antics of their old friends in the Sisters because they’ve been working alongside them for decades. They’ve long been allies in more than one sense. (The former group is, of course, offended by everything.)

David Brooks chose to be vicariously offended when the Dodgers awarded the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence for their community service before a game played on Pride Night — refusing even to notice the team’s magnanimity in honoring a San Francisco-based group before a game against the Giants. “When the Dodgers embraced the culture war spectacle, even just a little, they eroded the integrity of their sphere,” he wrote.

This is exactly what columnists like David Brooks were saying on April 15, 1947. I think Brooks half-realizes that, which is why he tries to qualify that a bit in his next sentence: “Personally, I think it’s great for teams to honor groups in their fan base, as with Pride Night or Hispanic Heritage Night; but I think it’s wrong for teams to honor organizations that ridicule other groups in their fan base.”

So no more group tickets for the Knights of Columbus, I guess.

But, again, what Brooks calls “ridicule” there is simply the deserved, earned shame that always falls to those who “pass by on the other side.” The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence didn’t make a mockery of the church. The church’s disdainful inaction throughout the AIDS crisis did that.

I said above that this column reminds me of something written about the Dodgers in 1947 or about gay activists in 1983, but let me give you one more date that everything Brooks says here recalls in vivid detail: October 3, 1992. Brooks is making the same muffled and muffling defense of injustice that — to our shame — we all nodded along with after Sinead O’Connor tore up that picture of John Paul II on Saturday Night Live:

And just seconds after that moment, with astonishing rapidity, we’ll hear the comforting voices of the pre-written consensus, the reasonable-sounding song of the Very Serious People reassuring us that we do not need to trouble ourselves with asking those rabble-rousing prophets and sages and scribes what it was they were trying to get us to look at. We’ll swiftly be told that even if it might have been brave or commendably idealistic for those misguided souls to have interrupted us all like that, there’s no need to disturb ourselves overmuch because if it were anything really important those people would have gone through the proper channels. Even if we vaguely suspect we might abstractly agree with the goals they seek, it’s more important in that moment to condemn their methods. After all, whatever it was those folks were so upset about, whatever made them so upsetting to us, it’s their fault that it’s still a problem because they didn’t have the decency to go about addressing it in the right way. Shouldn’t we go about things in the right and proper way?

That was more than 30 years ago, before “the Boston Globe’s investigation, and the Pennsylvania Grand Jury report, and the Houston Chronicle’s recent series,” before “the investigation of the Magdalene laundries and the Ryan Report and the mass-graves at Tuam.” Before the death of Savita Halappanavar and of all the American Savitas and Savitas-to-be now living in a post-Dobbs world.

It was, in other words, a time when more people might be expected to share the illusion that shapes Brooks’ entire column — the assumption that the US Conference of Catholic Bishops somehow possesses a moral high ground from which to look down upon the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence.