Looking back, they probably should’ve changed the name of the movie.

I like the name Big Trouble in Little China. I think it strikes the right tone and prepares the audience for the kind of action/comedy riff on classic kung fu movies the film provides. But, in retrospect, it didn’t prepare them for the movie’s unexpected twist and its biggest joke. As a result, John Carpenter’s cult-classic met with lukewarm reviews and flopped at the box office, failing to earn back the cost of its production during its initial release.

At the time, the movie’s failure was blamed on the success of The Golden Child, which came out just a few weeks later in 1986. Eddie Murphy’s action/comedy inspired by classic kung fu movies was a hit and the industry just figured audiences only had an appetite for one movie like that per summer. Big Trouble wound up eclipsed, they said, because audiences preferred the other movie that was just like it.

That makes sense, except that The Golden Child isn’t really anything at all like Big Trouble in Little China. Eddie Murphy was the movie star who starred in The Golden Child as the film’s hero, the Chosen One who defeats the Bad Guy and saves the day. Kurt Russell was the movie star who starred in Big Trouble in Little China, but he was not the hero or the Chosen One. He somehow manages to be physically present when the Bad Guy gets defeated and the day gets saved, but this happy outcome is as much in spite of him as because of him.

Jack Burton is the sidekick. “He thinks he’s the hero of the story but he’s not,” John Carpenter said. “Jack is a character who doesn’t know he’s a sidekick.”

That’s the central joke of the movie. It might even be the central theme of the movie. But it confounded audiences’ and critics’ expectations so much that many failed to notice it. They treated Jack Burton as a reliable narrator. Even worse, they treated the movie posters for Big Trouble in Little China as a reliable narrator. They saw Kurt Russell’s name in big letters above a big picture of Kurt Russell and John Carpenter’s name and they showed up expecting Snake Plissken, the impeccably cool, deadly competent, man-of-action antihero Russell had played in Carpenter’s earlier Escape From New York.

But Jack Burton is no Snake Plissken. And, again, that was kind of the whole point of the movie.

Thus if you look back at contemporary reviews of the movie, you’ll find critics complaining that Kurt Russell sometimes seems to be doing a bad John Wayne impression that he can’t even consistently maintain throughout the film. That’s nonsense. Kurt Russell does no such thing. Jack Burton is the one doing the bad, inconsistent John Wayne impression. Critics complained that, mysteriously, Russell seemed to have forgotten how to be the hero of an action movie. Because of those movie posters, and Snake Plissken, and Hollywood conventions, and the fact that Russell was the only white male in the cast — they were so sure that he had to be the hero of the story that they missed what every frame of film was actually showing them.

Even Dennis Dun — who played the actual hero of the story — recalls being initially confused when the director kept reminding him “You’re the hero.”

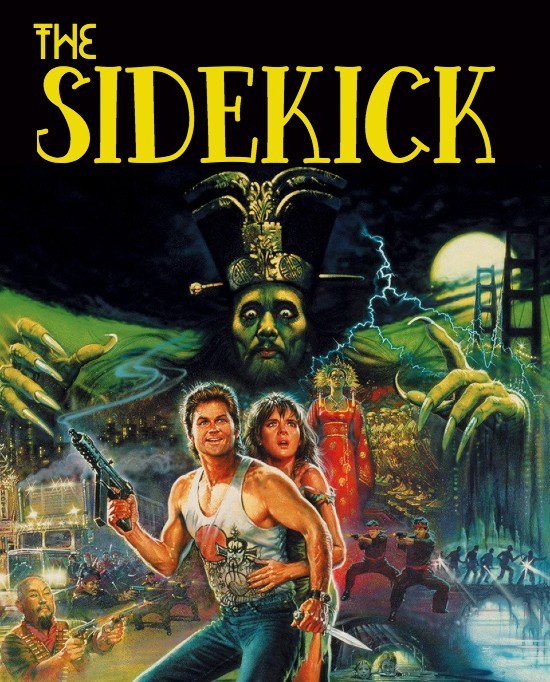

So probably they should’ve changed the name and the posters. Spelled it out so people would’ve known what to expect: “Kurt Russell is … The Sidekick! A John Carpenter film.”

Then maybe audiences and critics alike would’ve been better prepared for what they saw — the epic story of swashbuckling hero Wang Li who defeats the evil ancient sorcerer Lo Pan … as seen from the skewed point of view of out-of-his-depth trucker and amiable meathead Jack Burton, whose indomitable misplaced confidence serves as almost a form of bravery. Maybe then it would’ve been clearer that this was the story of a man who “doesn’t know he’s a sidekick,” and who “thinks he’s the hero of the story but he’s not.”

That’s still a good joke. And it’s still a relevant theme.

Watching Big Trouble in Little China today and the ways that Carpenter and Russell play with, deflate, and deconstruct the manly mythos of John Wayne, I can’t help but think of Kristin Kobes Du Mez’s book Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation. The central joke of that book is almost the same. It’s about men who are sure they’re the hero of the story, but they’re not. It’s about men who don’t realize they’re — at best — the sidekicks.

These pious Jack Burtons are all convinced that they must be the heroes of this story. They imagine themselves to be the Chosen Ones making a heroic stand in defense of Christianity, in defense of the gospel, in defense of the Bible, and in defense of God, the family, marriage, freedom, virtue, and America. They are the ones who will save the church, save the nation, save the world.

And they never manage to realize that they’re not the heroes of this story. They’re just the sidekicks. They’re Jack Burton.

Or, maybe, that’s too generous. I mean, Jack Burton isn’t always the most helpful sidekick. He repeatedly trips over his own ego and accidentally makes things worse, but at least he’s trying. Even at his clueless worst, Jack never (deliberately) crosses over to work for the other side.

So even though the manly men at the focus of Du Mez’s book share Kurt Russell’s swaggering John Wayne impression, the comparison to Jack Burton isn’t quite fair to poor Jack. They’re characters who think they’re the heroes of the story, but they’re not. They’re characters who don’t realize they’re not even the sidekick — they’re just Lo Pan’s Henchman No. 17.