“Are Southern Baptists ready for a world that despises Christians?” That’s Ron Hale’s Christian Post reaction to a First Things thumbsucker by Aaron Renn proposing Grand New Categories for white evangelicals’ ongoing struggle to begin to comprehend that the way Everyone Else sees them is not at all the same as the way they see themselves.

Renn’s scheme proposes a grand sweep of history in which white evangelicalism (conflated throughout with All of Christianity from Antioch to Mara Lago) was first viewed positively (CE 321 to 1994), then briefly neutrally (1994 to 2014), and now negatively (Obergefell and Black Man in White House through the present). It reads a bit like an undergrad paper on Berger’s Sacred Canopy written by an earnest student who, alas, did not finish reading the book or consider the possibility that the conversation may have continued and expanded since that book’s publication in 1967.

It’s the kind of Grand Scheme that makes sense as long as the undifferentiated plurals remain abstract and unexamined and as long as a fuzzy passive voice construct keeps essential nouns and subjects and agents obscured. The kind of Grand Scheme, in other words, that either breaks down entirely or hastily turns into something very different as soon as one asks something like “viewed positively by who?” or “whatcha mean ‘We,‘ kemosabe?” or “What, to the Slave, Is Your Fourth of July?”

Renn’s piece is getting a lot of buzz among institutional white evangelicalism and it’s worth noting as a good example of a growing trend of such pieces circulating there on this theme of “I’m Beginning to Suspect That Not Everyone Perceives Us as Their Moral Betters.”

The idiosyncratic details that make Renn’s variation stand out are those weirdly specific dates of 1994 and 2014. He isn’t suggesting that the lynchpin moments in all of church history were the Major League Baseball strike that spoiled the Expos’ best season and the subsequent release, 20 years later, of Taylor Swift’s 1989. But he may as well have been. He may as well be attributing these purported changes in how “society” perceives all of “Christianity” to the nefarious rise of Elvis. Aron. Presley.

The only things you need to note about Renn’s strange choice of those dates is how very, very recent they are* and how intensely parochial they require this framework to be. I mean, if you managed to exhaust my objections about History & Culture Not Working Like That and about “What part of ‘Give us Barabbas’ don’t you understand?” to the point where I became willing to start attempting to offer specific dates after which “society” came to view Christianity “negatively,” I suppose I’d toss out suggestions like, say, 1789 or 1619 or maybe, again, 321. And if you narrowed down the question to the particular, parochial consideration of white evangelicalism in America as perceived by American popular culture I suppose I’d start answering with a guess like, I dunno, May 2, 1963 or maybe three weeks later, or, at the latest, March 7, 1965.

But what Renn and Hale and their fellow institutional white evangelicals are really getting at here is fuzzier and more subjectively personal than that. They’re talking about a vibe.

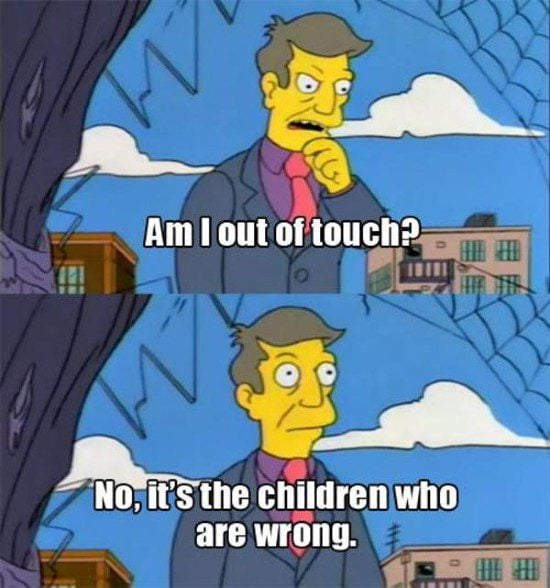

This argument really boils down to, “Hey, remember back, years ago when you’d tell the person next to you on a plane that you’re an evangelical minister and they’d react positively? That seems to have changed, somehow, and I’m uncomfortable with that.” It’s the Principal Skinner meme above in essay form (with a handful of half-understood Alasdair MacIntyre references thrown in).

And as always, this doesn’t really tell us much of anything about “society” or even about its overall abstract perceptions of white evangelicalism pre- or post-1994 or 2014. It just tells us that folks like Renn don’t get out much. It tells us about their perceptions of other people’s perceptions of them. And what it suggests is that they’re very, very slow on the uptake and not terribly interested in listening.

Hale amplifies the confusion by cranking things up from a vague prevailing negative perception in “society,” to “a world that despises Christians.” That just stirs up more mud, further clouding the distinctions between popularity, admiration, power, esteem, control, affection, revulsion, conscience, love, fear, and hate that muddle this and every other variation of this post-Christendom lamentation genre. This is why we keep winding up with nonsensical claims like the one in that NPR headline we looked at last week, “The Christian right is winning cultural battles while public opinion disagrees.”

The anxiety driving these pieces comes from the slowly dawning realization that even as the white Christian right reasserts its hegemony and tightens its grip on control, it’s becoming ever less respected. It is, again, “winning,” but not winning over. It’s succeeding in forcing others to abide by its stunted ideas of morality, but is failing utterly at convincing anyone that this “morality” is, in any way, moral.

* This is similar to the present-ism of Rapture Christianity, which reassures its adherents that in all of church history and all of human history, the Very Most Important Time is the one you, personally, are living in. More than that, these “Bible-prophecy scholars” say, most of the Bible and the most important bits of the Bible only apply here and now, for us, making us the extra special fortunate chosen ones. Renn’s pivotal moments in history have to be set in his lifetime and in the lifetime of his readers because what’s the point of proposing a Grand Scheme of History if it doesn’t make us all epochally important Grand People as well?

Part of that, too, is the nostalgia of childhood projected onto the world entire. As John Oliver said, the world we remember from years ago, when we were still children, seems happier and less complicated to us now because “we were 6 years old.”