From December 1, 2011, “‘Broken Words’ and the freedom to ask questions”

… Figures like Mark Noll, Jim Wallis or Tony Campolo are branded as dangerously “controversial” for occasionally kinda sorta nibbling around the edges of the big four — suggesting that perhaps, maybe, there might be a teensy bit of wiggle room to allow for a very slightly broader approach to these topics. But even that negligible deviation from the sacrosanct official stance carries a cost. And to go further would be to risk getting Cizik-ed — losing your job, your church, your chance of ever again being employed by any evangelical agency that relies on the current generation of donors (a wealthy, very conservative constituency determined to cut off any dissident who questions the big four). There’s a reason Mark Noll is now teaching at Notre Dame.

I believe there is a real generational shift taking place in American evangelicalism. Particularly when it comes to LGBT people, millennials consistently reject the misleading claims of the older generation. But I think this recent wave of dissident books by younger writers reflects more than just that.

I think it also reflects something Brian McLaren (another one of those dangerously “controversial” people) mentioned recently in response to a question about the no-dissent-allowed subject of abortion: “Relatively few people are in a position to talk about abortion as a theological and biblical question without having to worry about the consequences, meaning where their views would locate them in political, social, and even economic struggles.”

Younger writers don’t have to worry about those consequences. The evangelical establishment can’t threaten their privileges because they don’t have any privileges in that establishment. They don’t need to worry about an unflattering article in Christianity Today causing their speaking-fees to dry up because they’re not depending on any such speaking fees. They don’t have to worry about possibly offending the sensibilities of Howard Ahmanson and thereby losing their grant money because they’re not supported by such grants (and, happily for them, they may never even have heard of Howard Ahmanson).

Fear of punitive, retaliatory “consequences” prevents older evangelicals from speaking up and speaking out the way these younger writers do. More than that, it prevents them from even entertaining the thoughts that might lead them to having something to speak up and speak out about.

The same inconsistencies, contradictions and factual errors that trouble Jonathan Dudley are noticed — or at least glimpsed — by leaders of the older generation of the evangelical establishment. But they don’t even allow themselves the chance to give them a second thought because the consequences of that line of thought are all too clear.

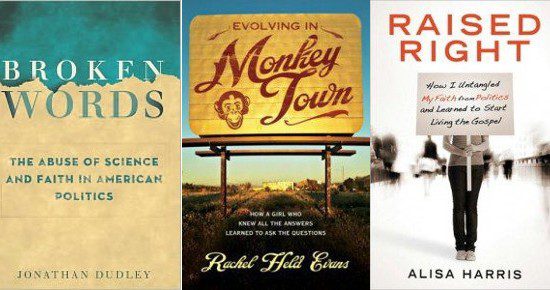

Rachel Held Evans and Alisa Harris are both thoughtful and perceptive people, but the troubling doubts they wrote about so well aren’t unique to them. The same doubts and reservations have occurred to scores of older evangelicals too, but that older generation had too much at stake to allow themselves to think through the implications of those doubts as thoughtfully as those younger writers have.

I’m not intending this as a criticism or judgement against that older generation. They are well and truly trapped. I won’t accuse them of timidity because their options really are constrained.

… Let me keep this strictly hypothetical and let me stress that I’m being strictly hypothetical. I’m not speculating about any actual evangelical leaders and whether they might fit this description, nor do I know for certain of any who do.

But let’s say you run an evangelical ministry helping at-risk kids in urban areas. You’ve never addressed any of the big four issues — never even been anywhere near them. After a couple of decades of hard work you’ve built a network of after-school tutoring programs, health clinics, food pantries, youth groups, mentoring networks — the full-court press. And it’s all dependent on the support of evangelical churches. That support is, in turn, contingent on the imprimatur of an ever-shifting list of “gatekeepers,” those self-appointed bishops — authors, radio hosts, columnists, activists, mega-church pastors, etc. — who define the boundaries of acceptable evangelical ideology.

You can quantify all the good things your ministry is doing, but it’s not about the numbers for you. You know these kids and their families. You love them. They have names and faces and they depend on you.

And then one day some interviewer asks you about one of the big four issues while preparing a puff piece for Charisma magazine. Or you’re asked to sign the latest of the endless stream of “declarations” that always seem to be circulating among evangelicals (declarations that often seem to exist specifically in order to keep everyone in line on the big four). And whatever you say will have a direct and measurable impact on all those kids and their families.

That’s the trap. Zugzwang — every move is a bad one.

And all I’m willing to say with confidence about the moral calculus involved is that I’m grateful I’m not in such a trap myself.

But I’m also grateful — very grateful — that this wave of younger writers isn’t caught in that trap either. And I’m grateful that they are therefore able to write with an honesty and candor I’ve learned I cannot expect from an older generation of American evangelicals.