There’s a lovely anecdote tucked in Bob Smietana’s Religion News Service report on the revival at Asbury University that provides context on what I think we should understand “revival” to mean. It’s about a man named Matt Erickson who was a student at Wheaton College in the 1990s when something similar happened there — a campus missions conference unexpectedly turned into five days of prayer and worship:

Erickson had come to the school in hopes of preparing for the ministry, but that calling had faded during his studies.

He recalled that during a campus missions conference, students began coming forward to ask for prayer and for spiritual renewal. That led first to an all-night prayer service and then to a series of evening meetings that ran late into the night. The last evening of the revival was a commissioning service for people who wanted to go into the ministry. Erickson said that experience led many of his friends into the pastorate or other Christian work.

“There was a sense of the presence of God,” he said, adding that it went beyond simply an emotional experience.

That “revival” did not transform all of Wheaton’s campus, it’s community, Chicago, or the world. It did not wake some mythical sleeping giant to create sweeping change in society or to spark dramatic new growth in the church. There were no mass conversions or mass baptisms or mass anything. This revival did not loose the fateful lightning of any terrible swift sword or set marching an army with a hundred circling camps.

But there was a young man who chose to become a pastor rather than to become, I dunno, the regional VP of sales for PharmaWidget-dot-com. His life was changed, but not instantly. The only short-term change was in his ambition. That new ambition (or calling) meant he faced more years of school and study. After that additional work and preparation, he became a minister, a person whose job involves ministering to others — sitting by bedsides and standing at gravesides, sharing in grace, rejoicing with those who rejoice and mourning with those who mourn. That’s a Good Thing.

But there was a young man who chose to become a pastor rather than to become, I dunno, the regional VP of sales for PharmaWidget-dot-com. His life was changed, but not instantly. The only short-term change was in his ambition. That new ambition (or calling) meant he faced more years of school and study. After that additional work and preparation, he became a minister, a person whose job involves ministering to others — sitting by bedsides and standing at gravesides, sharing in grace, rejoicing with those who rejoice and mourning with those who mourn. That’s a Good Thing.

That’s substantial, but more modest than the kind of radical upheaval and transformation that our revivalist theology, history, and folklore prepare us to expect.

All those “revival” meetings and prayers for revival are taking aim at something grander and more epic than that. Our hopes and prayers for revival carry this sense of Next Great Awakening Or Bust that causes us to overlook the actual results of what “revival” actually entails while also frustrating and forestalling the longed-for changes that we hope or expect to come on the day when revival, at last, descends from the heavens.

That all-or-nothing view of revival will only ever produce the latter result. It will never bring “revival.” I’m not sure it will even allow it.

Consider the most famous revival in American religious history, and probably the most influential, even though it never happened.

This revival began in 1896 in a Congregationalist church in Topeka, Kansas. A chance encounter raises a question that ignites a revolutionary movement of the Spirit, utterly transforming that church, its community, the entire city, and beyond. First we take Topeka, then we take Berlin.

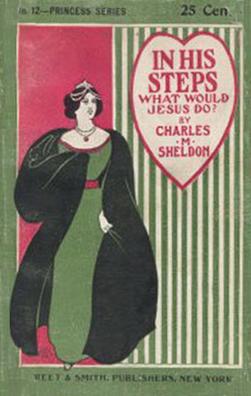

That’s the plot of Charles M. Sheldon’s In His Steps, one of the best-selling books of all time.* That book still shapes the way we think of Christian “revival,” and its influence can be seen in the responses of both those cheering and those criticizing the current revival unfolding at Asbury University.

Sheldon’s book is best known for its still-viral subtitle: “What Would Jesus Do?” That was the question that sparked the radical revival in his fictional church and it lives on in WWJD? T-shirts and jewelry. It can be a helpful, illuminating and constructive question but it is also — like the word “revival” — something of a Rorschach Test.

It’s a fascinating book. I first read the story in the Spire comics adaptation, then read the actual novel as well as some of Sheldon’s other books, such as The Heart of the World: A Story of Christian Socialism. That subtitle tells you where Sheldon was coming from. He was a Social Gospel guy and a socialist. He believed that What Jesus Would Do was, among other things, democratize ownership of the means of production (oh, and also pass the 18th Amendment).

That’s almost entirely forgotten today. If you see someone wearing a WWJD? T-shirt then it’s extremely unlikely that person is a socialist or an advocate of Prohibition. The lasting influence of Sheldon’s story doesn’t involve the substance of his imagined transformation of church and society, but the means of that transformation.

Radical, transformative change will come, Sheldon believed, but not through revolution, only through revival.

And what I’m suggesting here is that, well, no. No it won’t.

Revivalism is not sufficient to produce such change and revivalism is not necessary to produce such change. And please note here that this is true regardless of the theological, cultural, or political content of the change that any given person may be hoping to see.

I’m not talking here about the naive individualism that pervades revivalism — the notion that social transformation will (or can) be the product of personal transformation. We’ll come back to that, yet again, repeating all the usual business from Niebuhr and Orwell’s essay on Dickens, yada yada.

What I’m getting at here, rather, is the way that our mythology of revivalism causes us to misunderstand what revival does and does not mean and what being or having been revived entails.**

Revival is the soul-stirring, unsettling experience by which we come to understand and to accept the assignment. It is not the accomplishing of that assignment.

Revivalism confuses us on that point, causing us to mistake the former for the latter and, therefore, to never buckle down to begin the actual, difficult, sometimes tedious, work of the assignment itself.

There is no sleeping giant or magic bullet. Revival is not the process of change or the means of change. It is a reminder of the need for that change and an opportunity to commit ourselves to the work that change requires.

* Those who see revival as a product of active divine intervention may take a providential view of the epic screw-up that helped to make Sheldon’s novel such a blockbuster. His publisher, Chicago Advance, failed to copyright the book. As their initial sales took off, other publishers realized that and soon dozens of publishers were producing their own editions. That’s why it’s impossible to know exactly how many copies of the book were sold. But it was everywhere.

Sheldon, to his credit, just went with it. He wrote the book in the hope that it would be read by others, not that it would earn him a fortune in royalties, so he was pleased to see it become a phenomenon.

** The weirdest aspect of the current discussion of revival surrounding the services at Asbury is the way its forced to skirt around the usual language of reviving and awakening, lest this imagery lead where it inevitably and inexorably must: to the conclusion that God’s people ought to wake up and to stay awake. Accidentally phrase that a bit more colloquially and you’ll be breaking the law in Florida.