In 1915, US Marines invaded Haiti and took over the country, ruling it as a military dictatorship until 1934. The occupying military killed thousands of Haitians directly and imposed a system of unpaid, forced labor that led to thousands more dying in US-run work-camps.

This is a miserable, shameful chapter in American history. It’s a saga of reckless, brutal oppression in which the US military was deployed and degraded in service of private interests who enriched themselves by plundering the poorest of the poor. The end result was of no benefit to American national interests and it was an unmitigated disaster for the people of Haiti, creating the framework there for generations of dictatorial tyranny that defined that nation for most of the rest of the 20th century.

It’s an ugly story, devoid of nobility and honor and anything else that might make it attractive to contemplate. That makes it an extremely difficult story to talk about and so, mostly, we don’t talk about it. Even in history books and history classes. It’s an episode we rarely learn about and thus, also, an episode we steadfastly fail to learn from.

Even mentioning such aspects of American history will be perceived, by many, as a kind of attack — an attack on America as a whole but also, weirdly, as an attack on them personally. The word they’ve commandeered to express this lately is “woke,” but this recent innovation in the vocabulary of willful ignorance just gives a new name to an old refusal to discuss or mention anything like this. This is why people my age barely learned anything in school about slavery or the decimation of the Native Americans or Vietnam or Watergate, and the little that we were taught was, at best, misleading. These were ugly topics and therefore forbidden subjects.

Why, then, am I even mentioning this regrettable slice of American history? Is it because I hate America? Or is it because I am personally attacking some individual who will perceive this as an attempt to make them personally feel guilty or otherwise uncomfortable?

The timing certainly seems suspicious, given that this month is the 20th anniversary of the US-led invasion and occupation of Iraq. (Or, I suppose, it would seem suspicious, if that Big Round Number anniversary actually the basis for any substantial public discussion of that also-forbidden subject of unfortunate history.)

But actually I’ve been forced to think about this horrific, unjust and unjustifiable episode because of an article in Christianity Today.

Yes, Christianity Today.*

That’s where I read Andy Olsen’s extraordinary, thoughtful, fascinating piece on “What Evangelicals Owe Haiti.”

This may not be the first Christianity Today article to mention W.E.B. Du Bois or C.L.R. James, but I’m pretty sure it’s the first article in that publication to mention both of them positively.

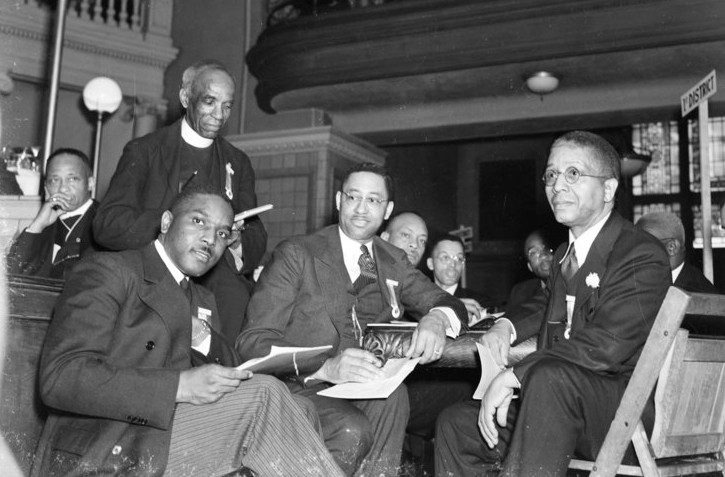

Olsen offers a long, fascinating, look at the history of American Protestant missionary work in Haiti. He breaks that history into two stages, with the first stage being in the 1800s up through the start of the US Marine dictatorship and the second stage beginning after the U.S. withdrew its troops. He also highlights the laudable history of some missionaries during that authoritarian occupation, two in particular: “One was S. E. Churchstone Lord, a minister with the African Methodist Episcopal Church. The other was L. Ton Evans, a white Baptist pastor funded by the Lott Carey Society, a Black missions agency.”

Lord and Evans witnessed the brutality and corruption of the American occupation of Haiti — which lasted from 1915 to 1934 — and they boldly opposed it, both on the ground in Haiti and through whatever connections they had back in the US. Lord rallied the NAACP and the Black press to oppose the occupation. Evans lobbied the State Department and the Wilson and Harding administrations. They were both harassed and threatened by US military officials in Haiti. (Evans was arrested, twice, for preaching — “trying to ‘Christianize and mentally and morally develop these low’ Haitians” — and threatened at gunpoint by US Marines).

Olsen leans on UNC historian Chris Davis for this history of Lord and Evans and it’s almost enough to make me want to read Davis’ whole dissertation on the subject. (I wish I’d read that back in 2003 when I was writing and marching and shouting in opposition to the invasion of Iraq.)

The post-occupation history of American Protestant mission work in Haiti is more complicated and, frankly, rather depressing, but Olsen doesn’t shy from describing the ways that this second wave of colonial missions enabled — and sometimes actively supported — the Duvalier dictatorships, or the ways that the “nation of NGOs” has prevented Haiti from developing organized government.

One of the themes Olsen stresses is the massive scale of American evangelical mission work in Haiti. “As of 2020,” he writes, “roughly 1,700 career missionaries were serving in Haiti—one for every 7,000 people.” Some of those missionaries are still doing the kind of work that characterized the first stage of missions in that country — serving in hospitals and schools throughout Haiti. But the largest aspect of this contemporary “mission work,” Olsen suggests, is the business of “short-term mission trips” — a kind of spiritual tourism industry that he estimates brings 85,000 American evangelicals to Haiti every year, turning the country into “a playground for spiritual retreat”:

“We built a vast network of facilities across the country offering camp-like experiences,” Olsen says, “whose benefits, mission leaders have not been shy to admit, mostly accrue to visitors.”

Meanwhile, the end of the Cold War meant the end of American interest in Haiti as a proxy in the battle between Soviet-style communism and “the free world.” That ended US support for the Duvaliers and, thus, their form of Haitian dictatorship. But it didn’t end US meddling in Haitians right to govern themselves, hence the removal, reinstatement, and second removal of Haiti’s popularly elected theologian-president Jean-Bertrand Aristide. And the ensuing years in which the country has struggled to govern itself despite not being allowed to form or fund any government that might interfere with the modern equivalents of the National City Bank of New York.

That brings us to the present crisis, which Olsen summarizes at the beginning of his article:

Militant gangs in Haiti control most of the capital, Port-au-Prince, and significant territory in other cities. They extract bribes at gunpoint for every case of diapers, bag of rice, box of gauze, and gallon of gasoline that moves in or out of its seaport. They set fire to neighborhoods and mount coordinated attacks on police stations. They drag rivals from emergency room beds and execute them outside.

Thus, Haiti’s economy is in free fall. Its annualized inflation verges on 50 percent. Fuel in some areas fetches $10 a gallon on the black market. The nation is slipping into famine—a term, believe it or not, rarely before used there. Thousands of its people are swamping boats bound for South Florida and marching across continents and piling up against the US-Mexico border.

To face these crises, there is no government. Haiti’s putative head of state, prime minister and acting president Ariel Henry, took office after the brazen and bizarre 2021 assassination of an unpopular president. But Henry is also unpopular. He has long overstayed the constitutional limits of his term. To replace him, Haiti would need to hold elections; its last elections were so long ago that every chair in its legislature sits empty.

But Haiti cannot safely hold elections, because law enforcement is consumed with a battle against gangs that have become so powerful that young men who want to join them are reportedly put on waitlists. …

Last October, Henry asked the international community for “the immediate deployment of a specialized armed force, in sufficient quantity” to help contain the gangs.

Olsen isn’t enthusiastic about the prospect of international military intervention. He recognizes that “send in the Marines” is a terrible idea that has failed repeatedly. And he recognizes that the last time an international force was sent to Haiti it resulted in a cholera outbreak that killed tens of thousands. But given the current desperation he still wonders despite that if Henry’s plea/plan for intervention might be the least bad of the bad options now facing Haiti.

I wish S.E. Churchstone Lord and L. Ton Evans were still around to talk to about that. I suspect they wouldn’t look kindly at the idea and that they would, instead, prefer to see action from the international community that has already invaded and occupied much of Haiti — that army of missionaries.

That is what Olsen also seems to hope for. “If there is a next era of missions in Haiti, it will be judged by what we do in this moment.” And “Foreign evangelicals cannot end Haiti’s problems, but we can stop doing our own thing. Careful listening—to what Haitian churches want, to what Haitian community leaders want—will be one of the most powerful tools for building back a nation.”

This article doesn’t have, or claim to have, all the answers. But it’s a long, thoughtful discussion that, at least, raises many of the right questions.

* Kudos to Christianity Today for running this. They knew it would likely bring them hate-mail and cancel-my-subscription flouncing from the 81% of white evangelicals who pounce on any excuse they can find to denounce CT as “woke.” (No, really, this is a thing — especially in the SBC.)

Fortunately, the volume of hate-mail prompted by this article should be somewhat limited due to the fact that it’s long and uses big words. The kind of white evangelicals who would be most horrified by Olsen’s mention of W.E.B. Du Bois are also the kind of white evangelicals least likely to have ever heard of him.