“Test everything; hold on to the good,” the scripture says. Thus also telling us not to hold on to whatever it is that can’t pass the test.

Toss that aside or let it fall away. That stuff is only weighing you down and slowing you down and wearing you down. The thought of leaving it behind may produce some anxiety prior to the doing so, but the experience of actually shedding it is the opposite of anxiety — it’s a rush of relief and liberation.

The command to “test everything; hold on to the good” is nearly 2,000 years old, but kids these days have a new word for it. Or, more accurately, old people these days who are the sort of old people who spend a lot of energy fretting about “kids these days” have a new word for it. They’re calling it “deconstruction.”

The new word doesn’t change the old experience: the unburdening, renewing, transforming joy that comes from no longer clinging with white knuckles to the things that cannot withstand the test, from letting go that which is not good.

So why is it that this experience of joy, relief, release, and liberation so often gets portrayed as something fearful and fraught? Why does it get confused and conflated with emotionally torturous spiritual crises and “dark nights of the soul”?

Well, in part I think that’s because there is a particular niche for whom “deconstruction” is fearful and frightening: People whose vocations or livelihoods have been dependent on sectarian institutions. When that’s your situation, “test everything” may seem like a threat to your boss or to your board of trustees, and therefore may prove to be a very real threat to your paycheck, your housing, and your healthcare.

Rick Pidcock writes about two cases of this dilemma in a Baptist News column titled “Why I have empathy for Karen Swallow Prior.”

Prior was an English professor at Liberty University for two decades before she joined the faculty of the Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in 2020. She left the Southern Baptist school earlier this year. “It has become clearer through heartfelt discussions with leadership and much self-reflection over the past few years that the institution and I do not share the same vision,” she wrote, “Therefore, I have made the difficult decision not to return to SEBTS in the fall. I don’t know what the Lord has next for me, but I’m excited to see how he directs my steps.”

That “I don’t know what the Lord has next for me” bit is a phrase we evangelicals sometimes use as a pious euphemism (“I don’t know what the Lord has next for me, Brad, but I feel God is calling me to date someone else”). But it can be terrifying when it’s literally true. Not knowing what’s next is scary.

It’s also unnerving to realize that your next chapter, whatever it turns out to be, is going to be something wholly new, something that quite likely puts you back at Step One. “A new beginning” sounds hopeful and promising, but it also carries with it the sense of “Ugh, another beginning? How did I invest all that time and effort just to end up back here at the beginning?” John Lennon’s “Starting Over” is kind of a sappy love song about joyous new beginnings, but there’s a big difference between what he was singing about and the sense of “Now I have to start all over, again, from scratch, and I ain’t 23 any more.”

Pidcock shares his own history of having to restart, reinvent, and rebuild after spending years studying and working in ultra-conservative white evangelicalism. He graduated with a BA in Bible from Bob Jones University, a degree that helped him to build a career as a church planter and worship leader in some very conservative parts of evangelicalism. But that degree and all of his work experience were suddenly of no use when he realized he now needed to find a vocation and build a life outside of those very conservative parts of evangelicalism.

This isn’t just about career and paycheck — though that is part of it, as those things are quite necessary. But we’re not talking here about mercenary considerations of “the money.” We’re talking about going from feeling like you know where you belong and what you’re supposed to be doing to suddenly no longer knowing that. One part of that is that your income, residence, insurance, and career are all suddenly up in the air. But the more upsetting and unsettling part may be that you’re unprepared for a quick, soft landing. You haven’t just deconstructed your way out of your current job, but you’ve deconstructed your whole résumé, which now describes you as qualified only to do the thing you’ve just realized you can no longer “share the same vision” with.

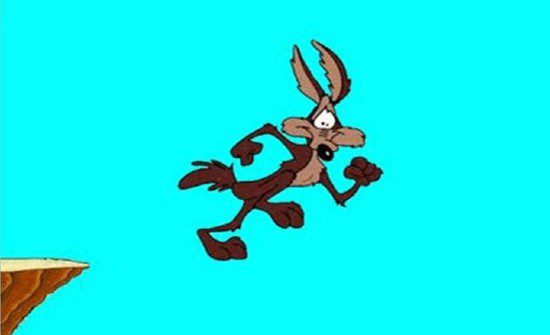

This is a leap of faith into the unknown. And you may have to be taking your whole family with you on that leap. And all of that is really scary.

This is why I think many of the people talking about “deconstruction” describe it as some daunting “dark night of the soul.” They’ve got vocations and careers built on their membership and belonging in a specific kind of sectarian institution and they realize that all of that is contingent on their continued membership and belonging in that specific sectarian realm. The notion of voluntarily leaving that behind is almost too traumatizing to contemplate.

Also, most of this discussion of “deconstruction” has to do with white evangelicals and “exvangelicals.” That means none of this is abstract or imaginary for these folks. They’ve seen it happen time and again — involuntarily — to well-respected colleagues whose loyalty and commitment to the shared vision wasn’t enough to keep them from getting Ciziked and Throckmortoned and farewelled into the outer darkness. When you think of deconstruction as a kind of self-farewelling, you’re bound to invest the idea with all sorts of dark, doubting, angst-ridden, fearful connotations.

But that’s not what it’s like — not even for those of us for whom it has meant wadding up our résumés and starting over on a blank sheet of paper.

Yes, testing everything can be testing. But nothing beats the realization that all that you’re left holding onto is that which you’ve found to be good.