It’s weird that the Wikipedia entry for this is called “Ursuline Convent riots.” That makes it sound like a case of nuns gone wild, but all the sisters did during these riots was flee and hide with the schoolchildren in their charge. I suppose a more accurate name for that entry — something like “That Time Protestants Lost Their Damn Minds and Burned Down a Convent and School in What Is Now Boston” — wouldn’t quite have the brevity Wikipedia seeks for the titles of its entries.

This happens a lot with riots. Encyclopedias, historians, and journalists tend to give them names that create confusion as to who, exactly, was running riot. These names tend to make the victims of mob violence sound like the perpetrators, as in the [Mobs Of White People Assaulting Mexican-American Youth Who Happen To Be Wearing] Zoot Suit Riots.

So to be clear: The Ursuline sisters of the convent school in Charlestown, Massachusetts, did not go on a rampage in August of 1834. They were the victims of that attack, forced to flee by a violent mob of Protestant New Englanders who were inflamed by anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic sentiment.

Previous mob violence directed at the convent school had been relatively minor — their stables were set on fire, and their dog had been killed. But by 1834, rumors had begun circulating that the sisters were luring and brainwashing local women, forcing them to stay at the convent against their will. Those rumors led to the town elders searching the convent and interviewing the women there, finding no evidence of any “mysterious women” being held against their will, tortured, sold into white slavery, or any of the other lurid accusations that had been circulating about the place. It was just a convent that ran a school.

Were the people who had been circulating and embellishing and working hard to believe those horror stories about the convent relieved to learn that those stories were not true?

They should have been. This was, after all, the pose they had been striking all along. Terrible goings on are happening behind those walls and we must put a stop to them. To save the children.

If that were any part of your genuine concern, then you would be relieved and overjoyed to learn that the children were safe. If you are not relieved, then whatever your concern was, it had nothing to do with those children. Those children were just a pretext or excuse to indulge in a fantasy in which you prove yourself a hero by imagining that you’re protecting children from monstrously evil women. As C.S. Lewis put it:

The real test is this. Suppose one reads a story of filthy atrocities in the paper. Then suppose that something turns up suggesting that the story might not be quite true, or not quite so bad as it was made out. Is one’s first feeling, “Thank God, even they aren’t quite so bad as that,” or is it a feeling of disappointment, and even a determination to cling to the first story for the sheer pleasure of thinking your enemies are as bad as possible? If it is the second then it is, I am afraid, the first step in a process which, if followed to the end, will make us into devils.

The Protestants of Charlestown failed Lewis’ test. After town officials announced that nothing untoward was happening in the convent, those who preferred the rumor to the reality felt “disappointment, and even a determination to cling to the first story for the sheer pleasure” of it. The rumor was just too much fun to allow it to be refuted.

And so, late at night on August 11, 1834, they marched out to the convent, ransacked the building, set it on fire, and desecrated the convent’s tomb.

In the name of protecting women and children, the mob set fire to a building housing dozens of women and children without any apparent concern for whether or not those women and children were still inside.

I wound up reading about this riot due to Paul Gutacker’s Anxious Bench post on “The Role of Church History in 1830s Nativism,” which isn’t nearly as dry as that title sounds. It includes an appearance by Samuel F.B. Morse — yes, the telegraph and dot-dash code guy. As we discussed here a few years ago, Samuel Morse was obsessed with the idea of a shadowy cabal of Jesuits secretly controlling the world, in contrast to his father, the pastor and Harvard trustee Jedidiah Morse, who had been obsessed with the idea of a shadowy cabal of anti-Jesuits secretly controlling the world.

I wound up reading about this riot due to Paul Gutacker’s Anxious Bench post on “The Role of Church History in 1830s Nativism,” which isn’t nearly as dry as that title sounds. It includes an appearance by Samuel F.B. Morse — yes, the telegraph and dot-dash code guy. As we discussed here a few years ago, Samuel Morse was obsessed with the idea of a shadowy cabal of Jesuits secretly controlling the world, in contrast to his father, the pastor and Harvard trustee Jedidiah Morse, who had been obsessed with the idea of a shadowy cabal of anti-Jesuits secretly controlling the world.

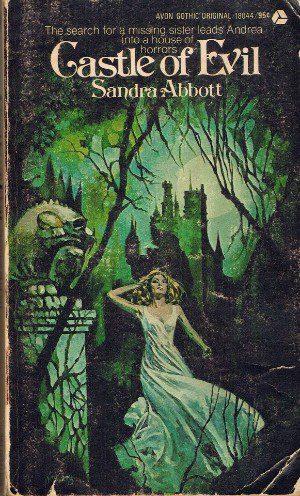

The older post linked there includes a discussion of Diana Butler Bass’ essay on “Kidnapping, Pedophilia, and the End of America,” which looks at the fever-dream conspiracy theories Protestants made up about their Catholic neighbors in the years after the Ursuline convent burned. Two best-selling books bore this false witness far and wide: Six Months in a Convent (1835) and The Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk (1836). Think of them as the Michelle Remembers and Satan Sellers of the Satanic Panic of the 1830s.

These books were much like the “Northanger horrids” lampooned by Jane Austen a few years earlier. They were overwrought Gothic novels posing as memoirs. Same plot: Innocent young woman ventures to a creepy old building full of hidden tunnels, dark secrets, and mysterious evils. Maria Monk dialed all that up to 11, and thus wound up where everyone winds up when they’re trying to describe something superlatively diabolical: Satanic baby-killers.

This is often what happens after you realize that you’ve stooped to barbaric violence of the sort that forces women and children to flee and hide. That realization might serve as an opportunity to repent, to make amends. It might lead you to drop to your knees in contrition, suddenly understanding that you’re the Bad Guy here.

Imagine: You’ve just burned down a school. A boarding school. You burned down a boarding school at night when all the children and the nuns who teach them are asleep in their beds. If you just look at the stark facts of that, it seems like you’ve become almost cartoonishly evil — what could possibly be worse then burning down a school full of nuns and children?

Surely you must repent. Or … or you could try to answer that question. What could be worse? How about someone murdering those children? Or, not just children, but babies. Abusing, then murdering babies. That would be worse than even the horrifyingly evil stuff you’ve just done yourself.

I mean, yes, you and everyone else now understands that you stand revealed as a school-burning, dog-killing, nun-abusing, child-terrifying liar. Granted, none of that is good, per se. But also none of that is as bad as if you were a Satan-worshipping baby murderer.

So all you’ve got to do to once again appear virtuous and heroic is accuse somebody else of being a Satan-worshipping baby murderer.

This is that step-by-step process Lewis said will turn us into devils. We participate in false accusations we know to be false because they made us feel better about ourselves — more virtuous and heroic. Faced with the real and serious harm done to others due to those false accusations our need to feel better about ourselves will become more intense and acute. And so we double down on the self-flattering lies by embracing and spreading even more outrageous and ludicrous false accusations.