When I worked for the paper, we were extremely scrupulous about the distinction between crimes and criminal allegations. Journalists must, like the legal system itself, defend the principle of “innocent until proven guilty.”

This was an expression of our commitment to accuracy, but it was also vitally important for avoiding legal liability. (There’s a reason that the latter half of the AP Stylebook and Libel Manual was a lot longer than the stylebook part.)

So you should never read a newspaper article stating that a “Killer goes to trial.” He ain’t a killer until the trial says he is. And until the trial makes that determination, the newspaper should not and cannot say otherwise. The accused is exactly and only that — accused. To say more would be presumptuous — assuming we have all the facts before we can be sure we do.

This principled practice, admittedly, seems strange when it involves some extremely public crime with numerous witnesses or what appears to be slam-dunk photographic evidence. “The suspect, allegedly seen here in the ATM video allegedly holding a gun to the victim’s head …” But even — maybe especially — in such apparently obvious cases, the commitment to accuracy and to the legal presumption of innocence matters. Maybe that’s not the suspect in the ATM video, just some uncanny lookalike who also just happens to have an identical neck tattoo with his name on it.

Sure, if you were placing a bet on the outcome of that suspect’s trial, you’d bet on his conviction as an apparent slam-dunk. Horses not zebras and Occam’s razor and all of that. But “odds are” isn’t the same as certainty or verifiable fact, and accuracy means reporting what you know and can confirm, not what you’re pretty sure is probably the case.

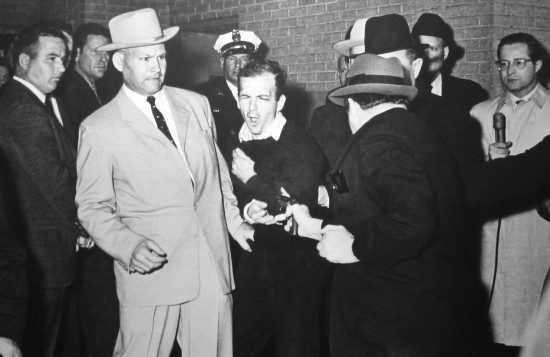

Consider the example of Jack Ruby, seen below in Robert H. Jackson’s Pulitzer-Prize-winning photograph shooting Lee Harvey Oswald in front of hordes of reporters and photographers, police officers, and court officials.

Before his trial, Ruby spoke publicly about his motives for that very public act of fatally shooting Oswald, and his defense never denied he did it, only that his actions were not premeditated. But even for all of that, until his actual conviction at trial, the rule was to say only that Ruby “allegedly” killed Oswald.

That initial conviction was overturned on legal technicalities and Ruby was granted a new trial, but Ruby died from cancer before that new trial could occur. That would have left him in “alleged” limbo forever — even though everybody saw him shoot Oswald — except that, before his death, Ruby fully confessed to the killing, and his own allegation could be taken as conclusive.

Alas, Ruby’s actions meant that Lee Harvey Oswald was never tried in court for the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. And because there was no trial to produce a conclusive verdict, Oswald has remained, forever, an alleged assassin — a status that feeds the wildest imaginations and leads to endless speculation.

The one exception I can think of to journalists’ strict adherence to this principle of “allegedly” is the case of former Pennsylvania State Treasurer Budd Dwyer. Dwyer took a $300,000 kickback from a California computing company in exchange for awarding them a state contract. Notice there’s no “allegedly” in that sentence. That’s not the exception here, that’s because Dwyer was tried and convicted, a court of law found him guilty of conspiracy, mail fraud, perjury and racketeering. So we can and do say that Budd Dwyer was guilty of corruption — that he took a bribe, full stop.

We can and should also add that Dwyer maintained his innocence throughout his trial and despite his conviction. That’s worth saying, too because, even when the courts have reached a conclusion based on apparently conclusive evidence, the courts don’t always get things right. In more than 30 years since his trial, no new evidence has emerged to support Dwyer’s claim of innocence, and the now-defunct Computer Technology Associates admitted to making the pay-off and accepted its punishment for its part in the crime, but for the record, Dwyer consistently protested that he was not guilty.

Dwyer was still serving as state treasurer at the time of his conviction but Pennsylvania law stated that he could not be removed from office until his sentencing. When he called a press conference on January 22, 1987, just before his sentencing hearing, the reporters gathered assumed Dwyer intended to announce his resignation.

Instead, Dwyer read from a long, rambling, oddly maudlin prepared statement which he eventually set aside. Then he abruptly pulled out a .357 Magnum revolver, stuck it in his mouth, and pulled the trigger. Budd Dwyer committed suicide on television.

This is the exception. I don’t think I’ve ever read any reporting that qualified that statement by saying that Dwyer “allegedly” killed himself. We all saw him do it. I saw him do it that night, on Channel 6 Action News, which chose to air the full video in both its 5 o’clock and 6 o’clock broadcasts that day. (“Move closer to your world, my friends …)

And no one ever speaks of Dwyer’s “apparent” suicide. That’s the abundance-of-caution word usually used in such cases until an official investigation confirms it. Suicide cases don’t go to trial, of course, but medical examiners and police detectives play the role here that the courts play for criminal allegations. Their investigation may determine that a suspected suicide was actually an accidental death, or — like in countless movies — a homicide staged to look like a suicide. Until they conduct that investigation, journalists avoid saying more than they can know — and avoid potential libel — by insisting on that cautious qualifier: apparent suicide.

But again, that word didn’t get employed in the case of Budd Dwyer because everyone saw it happen on TV. I don’t think this omission was a deliberate choice, just the result of the shock from his excessively public act. This blew apart and blew past our habitual cautious concerns about accuracy, uncertainty, or potential libel.

The extreme public nature of Dwyer’s actions had turned us all into witnesses, and witnesses bearing testimony have a duty not to qualify that testimony with words like “allegedly” or “apparently.” Their duty is to state, as clearly and plainly as they can, what it was they saw happen. To use anything other than such plain, straightforward language in our testimony would not seem principled, but merely pretentious — an artificial, disingenuous refusal to acknowledge what everybody had just seen happen.

All of which brings us to the multiple and multiplying criminal indictments against Donald J. Trump.

The first two sets of criminal indictments against the former president involve his alleged hush money payments to mistresses and his alleged theft and retention of classified documents, as well as his alleged obstruction of justice in both of those cases. We can read about those allegations and alleged crimes, and read some of the impressive evidence prosecutors have collected that appears to demonstrate Trump’s guilt. But we are not ourselves witnesses to those crimes.

It may seem somewhat strange to speak of Trump’s “alleged” crimes in the hush money case, given that his then-attorney Michael Cohen has already been convicted and served time in prison for his role as a co-conspirator in the same crime, but it’s still appropriate because we did not personally witness those crimes, they did not play out before our own eyes, and so it’s proper to wait for a court verdict before speaking with certainty of Trump’s guilt in the matter.

But the latter two, and far more serious, sets of indictments against Trump are different. The criminal allegations brought against him in Washington, DC, and in Georgia involve crimes that were committed publicly, nakedly, and defiantly before our very eyes. We saw them happen on TV and on social media in real time. We were there, in the room where it happened. We are not just consumers of reports in the press, but witnesses who can all testify to criminal actions we saw him do.

Most of us are not lawyers and cannot cite the line and language of specific criminal statutes in the way that experienced prosecutors like Jack Smith and Fani Willis can. Heck, most of us probably aren’t sure what “RICO” stands for, let alone the complexities of criminal law as it applies to public corruption and conspiracy. We mostly are not able to articulate the precise boundaries and distinctions that delineate between actions that are permitted and those that are prohibited.

But none of this has been subtle. Or hidden. Or anything that Trump and his co-conspirators have even attempted to hide.

We’ve all seen them nakedly, proudly, criming in public as hard as they can. We’ve seen them violating the law, the Constitution, and several of the Ten Commandments, repeatedly, for years on live TV and on tape. We’ve already seen much of the evidence presented by prosecutors because Trump and his co-conspirators posted it themselves, deliberately, on social media.

The election interference cases against Donald Trump, in other words, place us squarely in Jack Ruby and Budd Dwyer territory.

We know what happened. We all saw it happen.

We will continue to honor the bedrock principle of innocent until proven guilty, but that doesn’t change that we all know what we saw. Ain’t nothing “alleged” about it.