The irreplaceable Undine* introduces us to a 98-year-old cold case from Vinton, Iowa: “Murder of a Prohibitionist: The Myrtle Cook Mystery.”

Some murder cases are impossible to solve because of the inability to find anyone who had a discernible motive to kill the victim. Other cases grow cold because so many people had a motive, the police are left spoiled for choice. The following 1925 mystery is a perfect example of the latter.

If one wanted to be tactful, one could describe Myrtle Underwood Cook of Vinton, Iowa, as a strong-minded, courageous woman of deeply-held beliefs. Or you could be blunt and suggest that she was an overbearing, bigoted busybody. The 41-year old Mrs. Cook was a very active lady. She was an ardent prohibitionist–so ardent, that she habitually copied license plate numbers of cars she suspected were rum-running, and spied on her neighbors for any sign of illegal tippling. She made a perfect pest of herself to the local authorities, demanding that they go after anyone she believed was distributing alcohol. She managed to have a number of bootleggers arrested. When she wasn’t chasing after peddlers of bathtub gin, Mrs. Cook was head of the Benton County women’s organization of the Ku Klux Klan. Although fellow prohibitionists considered her a local hero, she was, unsurprisingly, not very popular in other circles. In fact, a sizable portion of Vinton’s residents saw her as a “meddler and a disagreeable gossip.”

It may seem inappropriate to describe the story of an apparent cold-blooded murder as “fun,” but I can’t help it. This story is sordid, horrible fun. Just consider the writerly aptitude of that name, Myrtle Underwood Cook. And then marvel at the central-casting perfection of the only picture we have of her.

The story is also funny — funny in much the same way that the ending of “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” is funny.

On September 7, 1925, Myrtle Cook was writing her speech for the next day’s meeting of the local Women’s Christian Temperance Union when she was killed by a bullet fired through her living room window.

So who shot Myrtle Cook? Spouses are always suspects, but Clifford Cook was out of town the night of the murder, just as he’d been out of town for most of their marriage. He wanted to get away from Myrtle, but didn’t seem to want to do away with her.

Mr. Cook, like many others, suggested his wife had been killed by rum-runners. This was during Prohibition, remember, when alcohol was illegal for the non-wealthy and thus was supplied by gangs of smugglers who were just as violent as drug gangs are nowadays. As president of the local WCTU chapter, Myrtle was a pebble in the shoe of those gangs. But local police investigated several members of local liquor smuggling gangs and didn’t find any evidence connecting any of them to the murder.

While the violent gangs Myrtle opposed were investigated, the violent gang she herself belonged to never was — probably because membership in the Klan, unlike membership in the WCTU, didn’t set her apart from or against most of her neighbors in Vinton. So even though the Klan had killed far more Americans than all of the rum-runners, bootleggers, and Chicago mobsters put together, Myrtle Cook’s Klan ties weren’t part of her murder investigation.

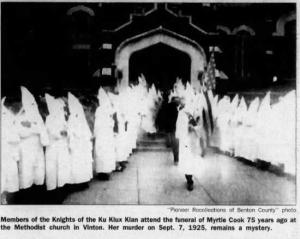

After all, how could the KKK be a suspect in Myrtle’s death when they gave her such a grand funeral?

The preacher who officiated the funeral dressed in the iconic white robe of Ku Klux Klan. Several other Klan members lined the sidewalk as Cook’s casket made its way from the church to Evergreen Cemetery. A cross was set on fire at the graveside ceremony. While Mrs. Cook was a member of the Christian Church, the funeral was held in the Methodist Church because it was larger. The pastors who officiated the service were both members of the KKK.

The Vinton Klan was ecumenical. It was a violent terrorist organization, yes — Vinton was an all-white sundown town in 1925 — but it was also a pre-eminent social club that included not just the local clergy but also, almost certainly, local law enforcement. Maybe the police never investigated the local Klan because, as members of that organization, they knew it wasn’t involved.

Or maybe police never investigated the Klan in Myrtle’s death because, as members of that organization, they knew it was.

This is my theory of the crime — one for which I have zero evidence, mind you. But all those hoods and robes aren’t free, you know. Running the biggest Klavern in Benton County takes money. And Prohibition meant there was a lot of money sloshing around for anyone involved in the now-illegal liquor business. It seems more than a little likely that some of that money went to local law enforcement — both official and unofficial. So my theory is that members of the local KKK were involved with rum-running in Vinton — either as direct operators or as indirect beneficiaries from bribes and kickbacks to ensure the business wasn’t interfered with.

After the ratification of the 18th Amendment and passage of the Volstead Act,** the once-daunting Temperance Union became the dog that caught the car. Membership in the WCTU waned and it didn’t pose much of a threat to those now making a fortune in the now-criminal enterprise of rum-running. But Myrtle Cook was a different matter. She was starting to cost them money.

So I think the police and the Klan — to the extent these were at all distinct categories — either knew who shot Myrtle Cook and covered it up, or else they were directly involved in the murder themselves.

That, at least, is how I would tell this story if I were the Coen brothers writing a screenplay, or Noah Hawley working on the plot for season five of Fargo.

I’d probably also bring Billy Sunday into the mix. This would be a teeny bit of a stretch since, based on what I’ve found in a quick-and-dirty Google hunt, Sunday’s revival campaign and traveling circus didn’t come through Vinton in 1925. (He was there a few years earlier and a few years later.)

I’d probably also bring Billy Sunday into the mix. This would be a teeny bit of a stretch since, based on what I’ve found in a quick-and-dirty Google hunt, Sunday’s revival campaign and traveling circus didn’t come through Vinton in 1925. (He was there a few years earlier and a few years later.)

But this is, after all, a story set in Iowa in the 1920s and it’s a story about Prohibitionist activists and the Ku Klux Klan, so how could it not include a visit from Billy Sunday?

During one of Billy Sunday’s revivals in Indiana in 1922, representatives from the local KKK showed up in full costume and presented him with a $50 donation and a letter commending him for promoting their Christian religion. Sunday told the audience that he was shocked and unsure of what to say, but grateful for the support for his ministry even from an organization to which, he insisted, he had no connection.

This was Sunday’s Klan shtick. He did this same bit, feigning surprise, almost everywhere he went because almost everywhere he went in the ’20s, this same thing happened:

The Palladium reported that Sunday was “dumbfounded,” even though this was not his first encounter with the Klan. “The klan [sic] has made a present to Mr. Sunday in every city he has been in during the last year. . . . Even the Klan in Sioux City did the same thing,” Sunday confidant Robert Matthews told the press.

So I’m putting Billy Sunday in the TV show, even if he wasn’t directly present in the actual story.

Myrtle Underwood Cook’s dual role as president of both the local WCTU chapter and of the women’s auxiliary of the local KKK had me re-reading this recent Religion Dispatches post excerpted from Andrew Monteith’s book, Christian Nationalism and the Birth of the War on Drugs, “From Christian Temperance to D.A.R.E. — The War on Drugs Has Its Roots in White Christian Nationalism.”

The WCTU started as a reformist and, in many ways, progressive movement. It was an attempt to impose one gargantuan, procrustean solution to a host of very real social ills and a source of actual human suffering. But it was also, from its earliest days, a movement that attracted activists driven by anti-immigrant sentiment, xenophobia, and racism and that welcomed their support and participation.

The Frances Willard House Museum faces that history with its exhibit and website “Truth-Telling: Frances Willard and Ida B. Wells.” (The short version: Wells was right; Willard was wrong, and also kinda racist.) Willard’s national leadership of the WCTU was, as the kids say these days, more than a bit problematic.

Work that down to the local level of local chapters in places like Vinton, Iowa, and you end up with Myrtle Cook and her dual leadership roles in the WCTU and the KKK.

The life and death of Myrtle Underwood Cook offers a window into the intersection between reformism and racism, between church and Klan, between the criminality of the rum-runners and the criminality of the white-robed clergy at her funeral. There’s more than enough here for the stuff of some prestigious university-press book of scholarly research.

I hope that somebody writes that book. I probably won’t read it — can’t usually afford those university press books — but I hope somebody writes it so I can read the reviews and the interviews with the author.

Mainly, though, I want to see this season of Fargo.

* I’ve been reading Undine’s Strange Company blog since approximately forever. Since dial-up maybe. It’s terrific fun — a fascinating, idiosyncratic, eclectic stream of strange tales, Gothic Americana, Forteana, disappearances, and true crime. The blog is true to its tag-line, a quote from Edgar Allan Poe: “We should pass over all biographies of ‘the good and the great,’ while we search carefully the slight records of wretches who died in prison, in Bedlam, or upon the gallows.”

Imagine having a clever, mordantly funny friend who works in an archive of old local newspapers and obscure, out-of-print books and getting the chance to ask them, “So, did you find anything interesting today?” It’s like that.

** The 18th Amendment did not automatically outlaw the sale and consumption of alcohol. It simply meant that any law that did so would now be constitutional as opposed to an unconstitutional interference with individual liberty and commerce. The Volstead Act was the actual law that enacted Prohibition. This is how the Constitution works, which is why the rights and protections afforded by the Reconstruction Amendments remain mostly theoretical, still awaiting the legislation that would enforce them.