• I’ve been a critical of a couple of posts from Richard Beck here recently — see here and here — which doesn’t reflect my overall opinion of his terrific blog, Experimental Theology, or of the man himself.

I only know Dr. Beck via his many years of blogging, but that has revealed him to be, generally, a mensch. He is often insightful and wise, and I’m genuinely enthused whenever I see a new post of his pop up in my RSS feed. I suppose that’s why I’m also genuinely disappointed when I find those posts disagreeable or something that calls for disagreement.

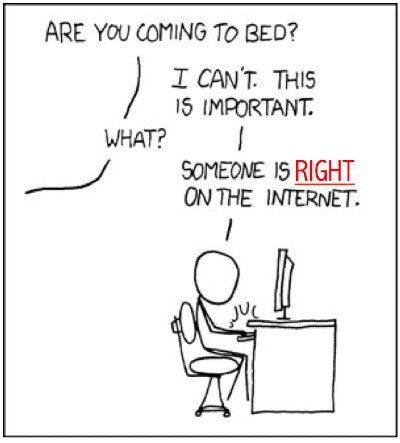

Think of that classic old xkcd cartoon — “This is important. … Someone is wrong on the internet.” That’s more likely to prompt a response than “Oh, hey, look — this person just made a good point.”

Think of that classic old xkcd cartoon — “This is important. … Someone is wrong on the internet.” That’s more likely to prompt a response than “Oh, hey, look — this person just made a good point.”

So let me balance things out here a bit by sharing a really excellent recent post from Beck’s blog: “The Most Controversial Verse in the Bible: Part 1, Exodus in the Plural.”

The verse in question here is Amos 9:7, which offers a string of ancient names and places that might, at first, distract readers from the full radically extreme meaning of what the don’t-call-me-a-prophet prophet Amos is saying:

“Are not you Israelites

the same to me as the Cushites?”

declares the Lord.

“Did I not bring Israel up from Egypt,

the Philistines from Caphtor

and the Arameans from Kir?”

Here’s Beck on the implications of that:

What we have here, in the words of Walter Brueggemann, is “Exodus in the plural.” Amos suggests that Israel’s Exodus wasn’t so special after all. Apparently, God performed an exodus for both the Philistines and the Arameans. What Israel thought made them unique and distinctive is something God had done for others. There wasn’t one Exodus, but many. Exodus in the plural.

Brueggemann’s longer discussion of the theological implications of Amos’ claim is rich and fascinating. So is Beck’s. And all of that theologizing is, I think, important.

But a big part of what Amos is saying there — or what God is saying, according to Amos — is something that we all should have learned from Mister Rogers a long time ago. Mister Rogers had many things to teach us as children, but the core of it came down to just two things: 1) You are infinitely valuable, special, wonderful, and unique; and 2) So is every other person you will ever meet.

• I also really liked where Beck was going with this recent post: “On Curses and Condemnation: The Narrative Resolution of the Deuteronomic Plotline.”

You can probably tell from that title that this one’s a little deeper into the theological weeds. But it’s worth the trip.

I read that post just a few days after listening to Pete Enns Ruin 2 Kings — an entertaining speed-run through that strange book in which Dr. Enns tries, and fails, to sort out all of the J-names among the rulers of the two kingdoms. That podcast does a great job of laying out what Beck calls “the Deuteronomic Plotline” — a vision of history that accounts for and explains defeat, destruction, and exile as something “we” deserve because we’ve sinned. That’s the history and the story that Beck says Paul is engaging with in the theology of his epistles — something we miss when we read it with the idea that it’s about our own, personal, Jesus:

In short, when we read the Bible we tend to read it narcissistically, believing that my particular sins bring me under my particular curse and that God is particularly sending me to hell. Me, me, me! Everything is about me! But this self-obsessed reading misunderstands Paul. Paul is telling a story. More specifically, he’s trying to finish a story, to get a story unstuck. Paul’s concerns about wrath, curse, judgment, and condemnation aren’t about you. His concerns are covenantal and narrative. His concerns are about the story of Israel being stuck in the mud. Given this, read Paul narratively rather than narcissistically.

OK, then.

• One more item from Beck’s blog, this is from part 3 of his series musing on the implications of Amos 9:7, which is all about Emeth the righteous Calormene in C.S. Lewis’ The Last Battle.

Beck concludes with a P.S. about that story:

C.S. Lewis is often lauded as an “evangelical saint.” Evangelicals love Lewis. And yet, I find it very odd that Lewis is not dinged more by evangelicals for the heterodox ideas he floats in books like The Great Divorce and The Last Battle.

Also too: Beer. Lewis loved his beer and did not at all trust the kinds of American Christians who seemed intent on taking it away from him. American evangelicals might not like what Lewis wrote about one single exceptional righteous Calormene, but what really ought to upset them is what he wrote about the Telmarines — their proxies in Prince Caspian, a book I was encouraged to read by devout white fundamentalists who’d clearly never understood it themselves.

Part of the explanation for Lewis not getting “dinged more by evangelicals,” I think, is that evangelicals read Lewis in the same chapter-and-verse way they’ve learned to read the Bible. Things get chopped up into bite-sized morsels, quotes pages on Good Reads, or page-a-day calendars. The stuff that doesn’t fit that format gets left aside.

A bigger part of the explanation for that, though, is that Lewis isn’t the one being “heterodox” there. He wasn’t the one who elevated extrabiblical folklore that rejects the justice and goodness of God into a sacrosanct and central doctrine of eternal conscience torment in “Hell.”

Lewis understood the dubious provenance of this folklore-turned-doctrine, so he never worried he was being “heterodox” in rejecting such an innovation. Instead, he challenged it as what it very clearly is: blasphemy and slander against God. That’s not an argument Team Hell is ever gonna win, so it’s not a fight they want to pick.

On the subject of C.S. Lewis and contemporary white evangelicalism, what intrigues me most lately is the stark contrast between Lewis’ idea of a kind of universal “Tao” familiar to all peoples and cultures and, on the opposite side, the parochial chauvinism of American evangelicals who see Christendom and white Western culture as having a unique understanding of morality, virtue, and human dignity that they imagine is inscrutable, inaccessible, and alien to every other religion and culture.

I kinda want to shout Amos 9:7 at people who make that argument, but, again, that’s not the point of today’s post.

• RIP Mike Knott, “a brash and brilliant pioneer of the alternative Christian rock scene who challenged the faithful to examine their faults and hypocrisies.”

The obituaries I’ve seen struggle to catalog all the bands and versions of bands and phases of Knott’s long, strange, prolific career. Listing all of those now is almost as hard as listing all of the bands he signed to his quixotic Blonde Vinyl label or to its more successful successor, Tooth & Nail. Put all of those lists together and there’s some good stuff in the mix. This 2017 piece by Michial Farmer is the best summary I’ve seen of Mike Knott’s life and discography: “A Primer on Christian Alternative Rock: Michael Knott.”

Part of the reason Knott wound up fronting seven or nine different bands (depending on how you count them) is because he was an alcoholic and a troubled guy who wasn’t easy to get along with. There were a lot of stories. But there were also a lot of songs. This one is probably my favorite: