Last week in various conversations I alluded to what I thought were two famous, widely known stories, only to have those I was speaking to be confused by my reference.

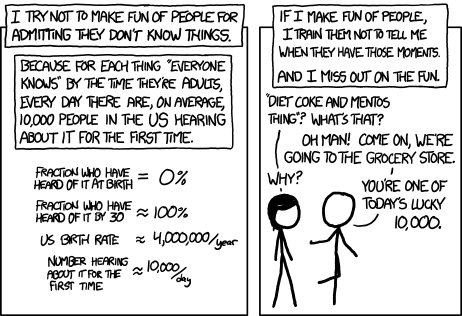

Both of those apparently not so widely known stories were Jesus stories from the Gospels. But don’t worry, this isn’t going to be one of those essays piously lamenting the sad decline of “biblical literacy.” If that’s all you can come up with because somebody missed a biblical allusion then, as Randall Munroe says, you’re missing out on the fun.

Yes, it might have been initially frustrating to realize that some folks had no idea what I meant by talking about “touching the hem of his garment,” but then I realized I had just met one of today’s lucky 10,000.

And so, just in case anyone reading this might also be among those lucky 10,000, I thought I’d take a quick look at the stories that the folks I talked to last week didn’t know. Because they’re great stories.

And also because I also want to come back to these later to explain why it was that I wound up alluding to them during multiple conversations recently. That’s not as great a story, but put that on pause for now.

I had a professor in seminary who said that Jesus taught both through parables and through “parabolic acts” — through deeds and actions and choices that played a similar role to the stories he often told. Sometimes Jesus told stories, and sometimes he did them.

These stories might fall under that category of “parabolic acts.” What’s interesting here, though, is that the parabolic action in these stories is not from Jesus. He’s not the main character here, or the protagonist.

These stories all involve Jesus. Other people’s encounters with him are the center and the focus of these stories. But these are still their stories, not his.* They are the stories of these other people making choices and driving the action. The “parabolic acts” are theirs. If these stories in the Gospels show us what the gospel is then it is these other characters doing that here.

The first of these characters is a woman who is very sick and, therefore, very poor. You might know her story from Sunday school or you might know it from Bill Monroe or from the Byrds or from Johnny Cash or from any of the other countless artists who have recorded “I Am a Pilgrim.”

The longest version of her story is in the shortest Gospel, in the fifth chapter of Mark:

Now there was a woman who had been suffering from a flow of blood for twelve years. She had endured much under many physicians and had spent all that she had, and she was no better but rather grew worse.

She had heard about Jesus and came up behind him in the crowd and touched his cloak, for she said, “If I but touch his cloak, I will be made well.” Immediately her flow of blood stopped, and she felt in her body that she was healed of her disease.

Immediately aware that power had gone forth from him, Jesus turned about in the crowd and said, “Who touched my cloak?” And his disciples said to him, “You see the crowd pressing in on you; how can you say, ‘Who touched me?’ ” He looked all around to see who had done it.

But the woman, knowing what had happened to her, came in fear and trembling, fell down before him, and told him the whole truth. He said to her, “Daughter, your faith has made you well; go in peace, and be healed of your disease.”

This woman’s sickness also made her religiously “unclean” and untouchable. Mark’s version of this story emphasizes that, highlighting her fear of punishment for having dared to reach out to touch this religious man. The Bible says she wasn’t allowed to do that.

But she doesn’t encounter punishment in this story. Instead, she finds healing.

That’s what happens in that story: a miraculous healing. I’m not always sure what to make of that. Lots of people will tell you that you can be healed by faith, and when you meet those people, you should probably guard your wallet. But the point of this story is not to have an abstract discussion of the possibility of this kind of miraculous healing. The point, as the song above understands, is that healing is necessary and healing is good, and that it ought not to be restricted from those we might think of as unclean.

There’s a miraculous healing in the second story, too. And here, again, the recipient is apparently an audacious outcast.

Here is the story as told in Luke 5:

One day while he was teaching, Pharisees and teachers of the law who had come from every village of Galilee and Judea and from Jerusalem were sitting nearby, and the power of the Lord was with him to heal.

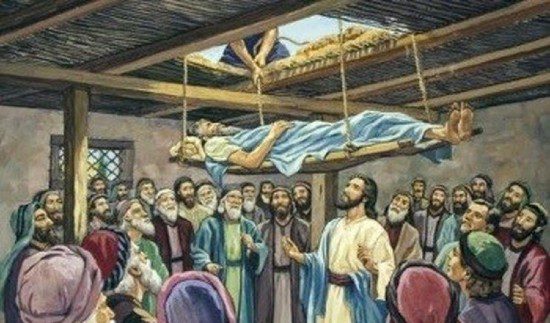

Just then some men came carrying a paralyzed man on a stretcher. They were trying to bring him in and lay him before Jesus, but, finding no way to bring him in because of the crowd, they went up on the roof and let him down on the stretcher through the tiles into the middle of the crowd in front of Jesus.

When he saw their faith, he said, “Friend, your sins are forgiven you.” Then the scribes and the Pharisees began to question, “Who is this who is speaking blasphemies? Who can forgive sins but God alone?”

When Jesus perceived their questionings, he answered them, “Why do you raise such questions in your hearts? Which is easier: to say, ‘Your sins are forgiven you,’ or to say, ‘Stand up and walk’?

“But so that you may know that the Son of Man has authority on earth to forgive sins”—he said to the one who was paralyzed—“I say to you, stand up and take your stretcher and go to your home.” Immediately he stood up before them, took what he had been lying on, and went to his home, glorifying God.

This was a favorite story for Sunday school teachers partly because this was a favorite story for Sunday school illustrators. An awful lot of Sunday school illustrations look the same — a bunch of bearded guys in robes and sandals standing around talking. But here you had action, with these men taking apart the roof to lower their friend down on a stretcher. (That action is more detailed in Mark’s version of this story, which says “they removed the roof above [Jesus], and after having dug through it, they let down the mat.”)

Most of my Sunday school teachers described the paralyzed man as a “beggar.” Could be. But he was neither homeless nor friendless. And his friends were good friends — the kind who were willing to take a big risk just for a long-shot chance of helping him out. Unlike the sick woman in the other story, they weren’t trembling with fear about what might happen to them as punishment for digging apart somebody’s roof directly above a room jam-packed with every respected religious leader for miles around.

Maybe those friends expected to be punished and they just factored that in as part of the cost they were willing to pay for any chance to help their friend. Maybe they were roofers and planned on fixing everything they had to damage in their desperate search for healing. Maybe — like the woman in the previous story — they just didn’t and couldn’t care about any of that anymore. Maybe they’d reached the point where their problem was so overwhelming, and where no one else seemed to care to help, that rules and punishments and all of that just didn’t matter any more.

Life gets like that sometimes. A big problem comes to define and to dominate everything. Nothing else matters. You “endure much” and you spend all you have, only to wind up growing worse. You get to a point where you can’t see anything else and you’d be willing to do anything just for any slight chance of fixing that problem.

When you get to that point of desperation and desolation, people will urge you to “have faith.”

Here is the strange and wonderful thing about these two stories. They look at that desperation and desolation — that inability to see or to care about anything other than the urgent need that has come to dominate your life — and they call that “faith.”

The bleeding woman and the men digging through the roof didn’t take desperate actions because they “believed in their hearts” that Jesus would provide the healing they needed. They were just out of options. Did they “believe”? Maybe. But I don’t know what that means and the people who say they know what it means haven’t convinced me they really do either.

Whatever the heroes of these stories “believed,” their stories tell us and show us that they needed this. In these stories, the extremity of that need forces them to act without any concern for anything else. And in these stories, that desperate need and desperate action is commended as “faith.”

So it’s not surprising that the people I talked to last week never learned these stories in Sunday school. I don’t think I really learned these stories in Sunday school either.

“Have faith,” it turns out, is a terrifying phrase. But whatever else it means, these stories tell us, it means this: Don’t give up. Reach out and grab hold of the hem of a garment. Dig through the roof if you have to.

* Bible stories like this are a bit like the Doctor Who episode “Blink.” That story is about the Doctor in the sense that we learn what he is like through the eyes of someone else. But that episode is not really his story. He’s not the hero of it. The hero, rather, is Carey Mulligan’s “Sally Sparrow,” a character who never appears or is ever mentioned again in the long-running series.

Oh, and if that reference doesn’t make sense to you because you’ve never watched Doctor Who and you’ve never seen “Blink” then congratulations, you’re one of today’s lucky 10,000!