The ads appealed to the very worst aspects of human nature.

The ads appealed. And they were found appealing.

They did not persuade so much as they allowed. They gave permission. And millions of our neighbors took that permission because they wanted it. And now they have it because they have given it to themselves.

I’m reminded of all of those puzzling conversations with acquaintances enamored by the premise of those “Purge” movies. Just imagine, they’d say, imagine what you could do if you could do anything — if there were no rules, no legal consequences, and you could do whatever you wanted. It seems the reason they find this premise so fascinating and alluring is that, for them, laws and legal consequences are the only — or at least the main — reason they’re not doing whatever it is they’re imagining right now. They seem to be admitting that they have no qualms about pillage and violence and vengeance per se, only concern about potentially being punished for it. Remove the threat of punishment and, they’re suggesting, anything goes.

I used to think this couldn’t really be true for them. Surely they wouldn’t really transform into violent thieves and sexual predators just because the fear of external punishment were suddenly removed.

But I’m less sure of that now. I’m less sure of a lot of things because millions of my neighbors found those ads appealing.

Most of them, I’m still sure, understood that this appeal was not to the best part of themselves. These ads asked them to be afraid, to be bullies, to hate strangers. The ads didn’t hide any of that. It was not possible, was not an option, to find them appealing or compelling without recognizing that such appeal was shameful. (“Round them up” and “put them in camps” the poll said. And no one who said yes to that failed to understand what they were saying yes to or what that always means about the person saying yes.)

And so part of the appeal of those ads was to promise freedom from that shame — something like “The Purge,” but instead of anarchic freedom from legal punishment, it was the idea of freedom from needing to worry about whether or not you could be proud of yourself. Be craven and cowardly without shame. Be selfish and bullying, without shame. Be hateful and hurtful, without shame.

The appeal of that constricts and ratchets ever tighter as it intensifies the shamefulness and thus the desire to embrace the shameless existence it promises.

The ads told them they had permission to be shameful and yet shameless. And so the ads were appealing.

What those millions of our neighbors will eventually realize — alas, too late — is that they are not the ones being given permission. They’re the ones giving it. And those they are giving it to are taking it and not giving it back. It’s theirs now. And now that they have it, they no longer need you to give it to them. They no longer need you at all.

This is what those folks fantasizing about the fantasy of The Purge failed to imagine. It’s what they failed to understand. The flip side of “I could do anything to anyone” is that anyone could do anything to you.

This is the permission that has been given and taken thanks to the shameless, lawless appeal of those ads.

It comes back, as so much does, to composer Frank Wilhoit’s crystalline description of conservatism: “Conservatism consists of exactly one proposition, to wit: There must be in-groups whom the law protects but does not bind, alongside out-groups whom the law binds but does not protect.”

This was the appeal of those ads and of the entire MAGA movement over the past 10 years. Join with us and you can be in the in-group. The law will protect you, but it will not constrain you. It seems like a sweet deal once one gets past the pesky shamefulness of it. But it’s never a good bet.

And it is always that: a bet. To embrace conservatism is to wager that those you have given permission to create and define “in-groups” and “out-groups” will perpetually regard you as one of them, as one of theirs, as a lifelong member in good standing of the in-group “whom the law protects but does not bind.”

But the in-group is small and it is always getting smaller. If you’re in it today there is no guarantee you will still be in it tomorrow. A year from now? Two years? Four years from now? Good luck with that. It’s far more likely that by then you’ll be out and no longer in. You will wind up, eventually — perhaps inevitably — among those whom the law binds, harshly, but does not protect.

This morning I sat on the porch in the dark and re-read Abraham Lincoln’s 1838 “Speech to the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield.” The news about my neighbors’ love for the sordid appeal of those ads was all too much and I was looking for that famous warning, that “if destruction be our lot” bit. I’m not sure if I was seeking that out of a desire for consolation or grim confirmation, but I wanted to read it again:

At what point shall we expect the approach of danger? By what means shall we fortify against it?—Shall we expect some transatlantic military giant, to step the Ocean, and crush us at a blow? Never!—All the armies of Europe, Asia and Africa combined, with all the treasure of the earth (our own excepted) in their military chest; with a Buonaparte for a commander, could not by force, take a drink from the Ohio, or make a track on the Blue Ridge, in a trial of a thousand years.

At what point then is the approach of danger to be expected? I answer, if it ever reach us, it must spring up amongst us. It cannot come from abroad. If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of free men, we must live through all time, or die by suicide.

Lincoln goes on to imagine the shape of such a national “suicide” and this bit — the part I hadn’t remembered and hadn’t been looking for — is the part that struck me this morning:

There is, even now, something of ill-omen, amongst us. I mean the increasing disregard for law which pervades the country; the growing disposition to substitute the wild and furious passions, in lieu of the sober judgment of Courts . . . . Accounts of outrages committed by mobs, form the every-day news of the times. They have pervaded the country, from New England to Louisiana . . . . Whatever, then, their cause may be, it is common to the whole country. . . .

But you are, perhaps, ready to ask, “What has this to do with the perpetuation of our political institutions?” . . . When men take it in their heads to day, to hang gamblers, or burn murderers, they should recollect, that, in the confusion usually attending such transactions, they will be as likely to hang or burn someone who is neither a gambler nor a murderer as one who is; and that, acting upon the example they set, the mob of tomorrow, may, and probably will, hang or burn some of them by the very same mistake. . . . [A]nd thus it goes on, step by step, till all the walls erected for the defense of the persons and property of individuals, are trodden down, and disregarded. But all this even, is not the full extent of the evil. By such examples, by instances of the perpetrators of such acts going unpunished, the lawless in spirit, are encouraged to become lawless in practice; and having been used to no restraint, but dread of punishment, they thus become, absolutely unrestrained. Having ever regarded Government as their deadliest bane, they make a jubilee of the suspension of its operations; and pray for nothing so much, as its total annihilation.

This lawlessness, “this mobocratic spirit,” was what he perceived as the gravest and likeliest threat, the one thing that could weaken the nation to the point of accepting the eventual rise of an authoritarian tyrant. Only by remembering that “to violate the law, is to … tear the character of his own, and his children’s liberty” would America be able to “frustrate the designs” of a would-be “Caesar or Napoleon.”

The sentiment of Lincoln’s speech is one we often describe as “conservative.” It’s a call to preserve institutions and laws against their erosion and deterioration. But there are also hints that even here, in 1838, as a young man not yet 30, Lincoln was starting to suspect that the biggest threat to a “nation of free men” was the suicidal contradiction of what Wilhoit describes as the sole proposition of conservatism. Despite his unqualified praise of “liberty and equal rights” in America, Lincoln was just beginning to recognize how America’s original sin of slavery was utterly incompatible with the “rule of law” that he argued was the only guarantor of that liberty. He’s singing in the key of Jefferson, but at times seems to realize that the whole project is doomed and damned so long as there are “in-groups whom the law protects but does not bind, alongside out-groups whom the law binds but does not protect.”

That same self-destroying conservative proposition was the promise of all of those winning ads and it promises, yet again, to make destruction our lot. It is a graver, surer threat to the freedom of any of us than even the lawless mob violence decried in young Lincoln’s speech.

I’m remembering Lincoln here because it’s important to remember that none of this is new. America, since its founding — and since its re-founding after Lincoln’s victory and death — has always had “in-groups” unrestrained by the bounds of law and out-groups bound, but never protected, by that same purported rule of law. Our politics has always been shaped and driven by white people desperate to maintain both categories in the hopes that they might somehow secure themselves a place in the former group.

It has happened before and it is happening again. We have had, at best, spasms of something better — fleeting moments of clarity when we briefly seemed to realize that neither liberty nor rights can sustainably exist without laws that both bind and protect us all. Black folks have tried to tell us. For centuries. But we still seem — as a nation — unable to abandon our fantasies of Purge-like pseudo-freedom and the lawless, suicidal nightmare Wilhoit described so well.

But if that hasn’t changed much since 1838, neither has the task before us. That task is the same as it was yesterday or last week or last year and it is the same as it will be tomorrow and next week and next year. We have to eradicate those false categories. We have to insist that no one is above the law and unbound by its constraints. And even more so we have to insist that no one is outside the law, unprotected by its rights.

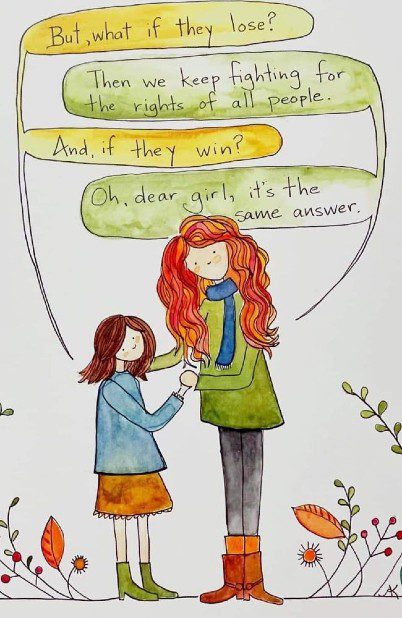

The cartoon above is sweet. It’s by an artist from Vermont who sells her work on Etsy and it looks it. It may seem somewhat sappy or sentimental and that may seem inappropriate for this moment, when the vicious appeal of those toxic ads has set the tone and the agenda for our country.

But that cartoon is also true.

The “mobocractic spirit” is inflamed. The lawless and violent have been newly empowered. Lives are at stake. The context has changed for the worse and the crisis is real, and acute, and urgent. But what we are called to do has not changed.

We are here to protect those whom the law will not protect. This is, among other things, the only way to protect ourselves.

What that will entail, more specifically, and what it is likely to cost, is something we will have to discuss in greater detail later. (But not too much later — we have only three months to plan and to prepare.)