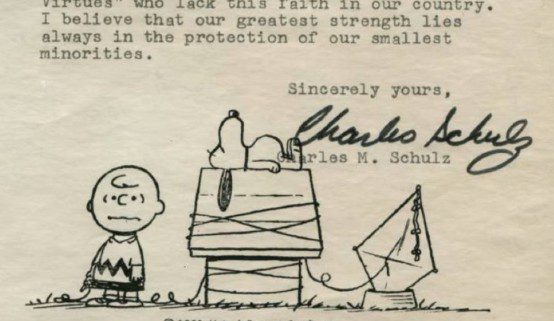

Charles M. Schulz, Letter to Joel Linton, age 10, 1970

I think it is more difficult these days to define what makes a good citizen than it has ever been before. Certainly all any of us can do is follow our own conscience and retain faith in our democracy. Sometimes it is the very people who cry out the loudest in favor of getting back to what they call “American Virtues” who lack this faith in our country. I believe that our greatest strength lies always in the protection of our smallest minorities.

Lucy Sixsmith, “Justin Welby Should Resign”

Alternatively, they could stay at home on Sunday mornings, have another cup of tea and think it all over. That’s what I do, so I’m not about to berate anyone else for giving up. Only for clinging on to power by their finger-tips, as if God will only get by if he keeps certain people in certain posts. Those who presume to teach will be judged more strictly. Grace (Simone Weil says) is the law of the descending movement. What if Christians acted as if what mattered was not their success but Christ on the cross — a God who suffered, and the children whose suffering he understood better than anyone? They all ought to resign if they forgot that, if they thought the gospel was anything other than that.

Dahlia Lithwick, “How Originalism Ate the Law”

Shackling one’s understanding of the law to the drunken methodology of “originalism” doesn’t simply ignore the technological realities of modern life, like serial numbers, and bump stocks, and the vagaries of online content moderation. It also turns every judge and lawyer into a part-time Revolutionary War reenactor and part-time recreational archivist (whose bare-bones understanding of history tends to become immediately obvious). As the Supreme Court burns down decades of doctrinal progress and a century of modern government, it leaves only skid marks in its wake. What is a judge to do? She must make her best guesses about whose history matters and wait to see what the history oracles will permit. No system of law that relies on stability, predictability, and consistency can function when “history” means merely whatever five amateur historians decide it means at any given moment.

Richard Hofstadter, in “The Paranoid Style in American Politics” (via)

If, after our historically discontinuous examples of the paranoid style, we now take the long jump to the contemporary right wing, we find some rather important differences from the nineteenth-century movements. The spokesmen of those earlier movements felt that they stood for causes and personal types that were still in possession of their country—that they were fending off threats to a still established way of life. But the modern right wing, as Daniel Bell has put it, feels dispossessed: America has been largely taken away from them and their kind, though they are determined to try to repossess it and to prevent the final destructive act of subversion. The old American virtues have already been eaten away by cosmopolitans and intellectuals; the old competitive capitalism has been gradually undermined by socialistic and communistic schemers; the old national security and independence have been destroyed by treasonous plots, having as their most powerful agents not merely outsiders and foreigners as of old but major statesmen who are at the very centers of American power. Their predecessors had discovered conspiracies; the modern radical right finds conspiracy to be betrayal from on high.

Malcolm Foley, “Lord, Give Us a King to Lead Us”

The call for the people of God is endurance and faithfulness. It is the call to be relentless in standing alongside those who are trampled, imprisoned, starved and killed by the state. It is the call to bear witness to a Gospel that promises personal, communal and cosmic redemption. It is to resist the domination and exploitation of the empire, to resist the violence of the empire and to resist the vitriolic, propagandistic lies of the empire. The people of God hate (at least) three things, for they are three things that the Lord hates: the trampling of the poor, the killing of the weak, and lies about one another and about the Lord. We can build communities that resist those particular things by the power of the Holy Spirit. Such work has always been necessary.

Noah Berlatsky, “The Lamp and Its Shadow”

“The New Colossus” is a powerful example of how Jewish-American diaspora identity can lead to a broad commitment to diversity, democracy, and equality for all. Most lights, however, also cast a shadow. The shadow in this case is the poem “1492,” a powerful, disturbing exercise in Jewish-American nationalist mythmaking, which imagines land magically emptied of indigenous people for the convenience and salvation of persecuted Jews.

Which poem—“The New Colossus” or “1492”—is the true expression of Jewish-American diaspora? The answer is clearly, both. Jewish people in America, like Lazarus, have built on their experience of persecution and exile to identify with and fight for all persecuted people and all exiles. And some Jewish people in America have also, like Lazarus, built on their experience of success and empowerment to denigrate and deny the experiences of those who have been less successful in America and elsewhere.

The diaspora, by its nature, is multiple. It can be a light of freedom and equality for all. Or it can be an ethnonationalist fire, scourging those considered less worthy. It’s up to us to choose the better lamp, and the better Lazarus.