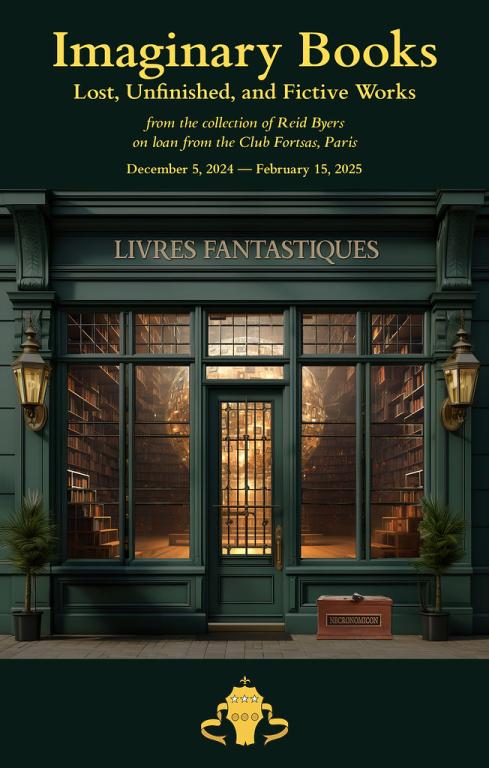

I love this story from the Guardian, “A whimsical new exhibition assembles a range of books that don’t exist.”

This exhibit is just so much fun. It’s people both having fun and creating fun by designing and presenting editions of these “books that don’t exist.”

That includes several categories here, including “lost books” (real texts for which we have no surviving copies), “unfinished books,” and — my favorite section — “fictive books.” These are “books that exist only in other books”:

This includes Rules & Traffic Regulations That May Not Be Bent or Broken, a driver’s handbook mentioned in Norman Juster’s The Phantom Tollbooth, which looks much like a traveler’s manual from the 1960s. Or The Songs of the Jabberwock, bound in purple and printed backwards, “pretty much as Alice found it sitting right inside the mirror”, said [Reid] Byers. A copy of Nymphs and Their Ways, glanced by Lucy on Mr Tumnus’s shelf in The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, decorated with a Romantic-era painting of bathing women. And a maroon-colored version of The Lady Who Loved Lighting by Clare Quilty, who was murdered by Humbert Humbert in Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita – though, as Humbert Humbert is a famously unreliable narrator, we don’t really know if he even existed. It’s a unique specimen of the collection – “a book written by a character who does not exist, even in the book of origin. So it’s doubly imaginary,” Byers explained.

Oooh. This is like a library or book-shop version of my ever-growing playlist of songs that exist only in other songs (“The Tennessee Waltz,” “The Monster Mash,” “Night of the Johnstown Flood,” etc.).

You can explore the exhibit online as well.

I wish they’d included the original, untranslated Red Book of Westmarch. And then my mind started racing, thinking about all the other fictive books I’d want to see added to this beautiful exhibit. And then I tripped over The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch, and then the delight drained away a bit.

But anyway, Adrian Horton’s article on this exhibit also taught me a fantastic, new-to-me word:

Imaginary Books is, as Byers will concede, a true and sincere gag, down to its listed “sponsorship” by the Mountweazel Foundation in Faraway Hills, New York. (A mountweazel being, of course, a term for a fake entry in a reference work, usually planted to catch copyright infringement.)

The etymology of “mountweazel” is just wonderful:

The neologism Mountweazel was coined by The New Yorker writer Henry Alford in an article that mentioned a fictitious biographical entry intentionally placed as a copyright trap in the 1975 New Columbia Encyclopedia. The entry described Lillian Virginia Mountweazel as a fountain designer turned photographer, who died in an explosion while on assignment for Combustibles magazine. Allegedly, she was widely known for her photo-essays of unusual subject matter, including New York City buses, the cemeteries of Paris, and rural American mailboxes. According to the encyclopedia’s editor, it is a tradition for encyclopedias to put a fake entry to trap competitors for plagiarism. The surname came to be associated with all such fictitious entries.

That’s from the Wikipedia entry on “Fictitious entries,” which makes me wonder if Wikipedia itself has any. That entry also mentions “trap streets,” a form of fictitious entry that I’ve been fascinated with ever since I was a kid on a bicycle.

Back in middle school, my friends and I went everywhere on our bikes. We usually just wandered, but sometimes we planned long journeys using a road atlas of Middlesex County. That’s how we learned about trap streets.

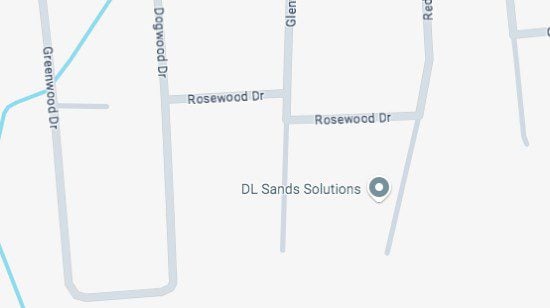

Our journeys usually began from Doug’s house. He lived on Rosewood Drive, in Piscataway, a short street that ran between two dead ends, like the crossbar on a capital H.

That’s how it looks on Google Maps,* but it’s not what our county atlas showed. That atlas included a street that didn’t exist. It had an “Elmwood Drive” connecting those two dead-end streets south of Rosewood. We were confounded by this mystery. We took the road atlas and pedaled down to the dead ends of both Glenwood and Redwood, confirming with our own eyes and feet that no such thing as “Elmwood Drive” existed where we stood. It was still all just scrubby woods with bike trails that we avoided because that was where the Big Kids hung out. (Avoiding the Big Kids is an important rule during the summers when you’re in middle school.)

We presented this mystery to Doug’s dad, who explained to us about “trap streets” and how map-makers had to invent and include small errors to defend their copyright against plagiarists who might try to steal their work. We were fascinated by this idea — particularly after he suggested that there were probably small, deliberately false details on every page of that road atlas.

I wrote about this here recently 18 years ago, in “The Street That Wasn’t There,” trying to describe how the existence of trap streets and the imperfection of maps helped guide me to a softer landing out of fundamentalism:

The disparity between map and terrain forced me to make that distinction, and to recognize the possibility of that distinction, which wasn’t something the fundamentalist church and school I attended were interested in recognizing.

… When forced, by a conflict between them, to choose between the text and the real world, I decided to go with the real world. I decided, in effect if not in these precise words, that this is what maps are for, this is what constitutes mapness. I didn’t throw away my county atlas — the vast majority of it remained trustworthy, reliable, and indispensable — but I decided, from there on, to treat maps as maps and not to try riding down streets that weren’t really there.

Whether it’s a trap street or a mountweazel, a fictitious entry is a deliberate disparity between text and reality. The fact and nature of that disparity, in a sense, breaks the spell of fundamentalism.

That genuine entry on fictitious entries includes two examples of copyright-traps from dictionaries. One is a textbook mountweazel, an entry for the word “jungftak” which is a fanciful invention, a “Persian bird, the male of which had only one wing, on the right side, and the female only one wing, on the left side; instead of the missing wings, the male had a hook of bone, and the female an eyelet of bone, and it was by uniting hook and eye that they were enabled to fly.” That entry is fictitious because there is no such bird.

But the other dictionary example complicates things. It’s an entry for “esquivalience.” which is a made-up word meaning “the willful avoidance of one’s official responsibilities.”

“Esquivalience” is not the only made-up word in that dictionary — all of the words included in that book were invented. Unlike trap streets or Combustibles magazine or Nymphs and Their Ways, imaginary words do not remain imaginary and fictitious. Imagined words are imagined into existence. “Jungftak” is not an imaginary word. It is a real word for an imaginary creature — a word that exists for a bird that doesn’t.

The fundamentalism I mentioned above is the white Christian fundamentalism of the church and school I grew up in. But even many people far removed from that religious context share its outlook when it comes to dictionaries. They cite dictionary definitions as inerrant, infallible proof texts. They assert that a word means what it means because the dictionary says so, and not the other way around. (This is usually accompanied by the implicit belief that denotation is the sole meaning of meaning, and that connotation is insignificant.)

Fictitious entries in dictionaries challenge this fundamentalist outlook in at least two ways. First, they demonstrate that dictionaries are not inerrant and infallible — either because they contain deliberate errors or else because they do not need to do so, because they naturally vary in a way that inerrant and infallible texts would not if they corresponded to the world the way fundamentalists think they must. And, secondly, because dictionary-fundies will be sure they’re either supposed to accept or to reject fictitious entries, but they’re dizzily unsure which to do. What does or does not make “esquivalience” a “real” word? Being included in the dictionary? Or usage? Neither answer is going to sit well with our fundie friends.

Copyright traps began as lawyerly devices to prevent copyright violations, and I’m proud of us humans for the way we’ve turned something litigious into a realm of whimsy, humor, and delight. It’s just a lovely added bonus that mountweazels wind up doing to fundamentalist ideology the same thing that happened to Ms. Mountweazel herself on that final, fateful photoshoot.

Anyway, do click over to see Reid Byers’ lovely illustrations of imaginary books.

* Whatever “DL Sands Solutions” is, that wasn’t there when we were kids. Maybe somebody has opened a business in a split-level ranch house on a dead-end street? Or maybe DL Sands Solutions is, itself, a fictitious entry — a phantom business included for copyright reasons.