"Nature and Nature's God" was Thomas Jefferson's lovely phrase for the basis of the rights we asserted in the Declaration of Independence. That was his shorthand answer to the question "Sez who?" He didn't have time in that document for a treatise on the basis, source or origin of human rights. His point wasn't to make the case that such rights existed, or to explain why they did or where they came from. His main concern, rather, was the meaning and the implication of those rights in that particular time and place.

For some of Jefferson's readers and hearers, such rights arose mainly from sectarian religious sources. For others, they arose mainly from the secular philosophy of the Enlightenment. Wanting his Declaration to appeal as broadly as possible, Jefferson split the difference with "Nature and Nature's God."

We don't encounter the "Sez who?" problem when discussing civil rights. Civil rights find their basis in civil law and constitutions. When arguing for equal access to the civil right of marriage, for example, David Boies and Ted Olson (!) do not need to appeal to "Nature and Nature's God" because they have the 14th Amendment with its legal guarantees of equal protection as a civil right.

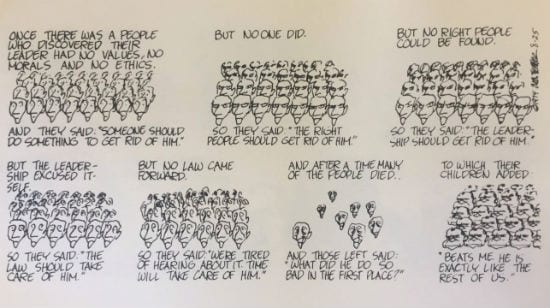

During the American civil rights movement — which reclaimed the legal rights of the 14th Amendment that had been surrendered to a century of domestic terrorism and the lawless laws of Jim Crow — Martin Luther King and the other leaders of the movement were able to appeal to civil law. They had the U.S. Constitution on their side.

The argument was much more difficult for the 19th-century abolitionists. Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison were arguing for human rights that were not yet recognized as civil rights and they were opposed at every step by that same U.S. Constitution. (Garrison called it, "the most bloody and heaven-daring arrangement ever made by men for the continuance and protection of a system of the most atrocious villainy ever exhibited on earth," a document to be "held in everlasting infamy by the friends of justice and humanity throughout the world." And there he was just warming up.)

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is, in part, an effort to make the struggle for the recognition of human rights more like the struggle for civil rights. By getting all the nations of the world to acknowledge the formal, legal existence of human rights, that document provides the peoples of those nations with a legal basis for claiming them.

In theory, at least. The response to such claims is still often the one given in Tianenmen Square — You have rights? We have tanks.

In recent years a separate challenge to the existence of universal human rights has come from people like Mahathir bin Mohamad, the former prime minister of Malaysia, who argued that human rights are a parochial western construct invented by those seeking to impose American values on the rest of the world. Thousands of indigenous Malaysian voices called bullshit on that claim, but it was a reminder that the simple assertion of human rights also sometimes does need to be supported by the longer, more complicated task of making the case for why such rights exist — the case that such rights do, in fact, exist as truly and undeniably as any line of tanks.

That case won't look or sound exactly the same in every time and place. Some will arrive at the conclusion due to sectarian religious reasoning. When speaking to or writing for an exclusively Christian audience, I have made the case for human rights based solely on sectarian Christian grounds. The Jewish religious case for human rights is well established. The Islamic case, while less established in law and practice, is likewise solid, and if it has not been universally adopted, it has also not been successfully refuted. I do not know enough of Hinduism to follow the argument in that tradition, but from what I understand the Ghandians and the Dalit movement are able to present a forceful case for human rights in both secular and sectarian terms.

Purely secular arguments for the existence of human rights also vary. Reason gives us many reasons and many paths of reasoning that all lead to this same conclusion.

And it is that conclusion that concerns me most. Nature and Nature's God, Nature or Nature's God — the point is these rights do exist and when we have the need to claim them it is more expedient simply to assert or reassert their existence, to point to the fact of their existence, and to move on from there.

I would put the criteria and the conclusions of the just war tradition in the same category. They too can be grounded in a variety of different secular and sectarian arguments. They too exist independent of those arguments, as things that are, in Jefferson's righteously impatient language, "self-evident." They too exist as a necessary response to the logic of tanks.

And just as with human rights, it is often necessary and expedient to assert them with little more than a cursory reference to "Nature and Nature's God." Our brief lifespan won't allow for us on every occasion to go back to square one and rehearse yet again the reasons for the validity of these principles every time we have the need to refer to them.

So instead we simple state them and cite them. "These are the rules." Shorter, but still true.

(All of which is just to say that if anyone reading the prior post was uncomfortable with its aggressively deontological tone — "rules, rules, rules," "categorical" even — well, so was I.)