Our tour leader was a short, wry, charming Armenian man named Tony. He was a history scholar and an irreverent cynic — both qualities that suited him well for the task of guiding a group of American college students all over Israel and the West Bank for several weeks in January, 1990.

As we prepared to visit each of the many sites on our formal itinerary, Tony would briefly summarize the prevailing scholarly understanding of its history, often highlighting the contrast between that view and the more popular legends surrounding many places. And, if you prodded him a very little, he’d also sometimes share his own opinion — which was sometimes persuasive, sometimes outrageous, and sometimes both.

Before we visited the Temple Mount, Tony offered his nutshell opinion of the site’s history. Before David, he said, the holiest site in Judaism was Hebron, regarded as the location of the Cave of the Patriarchs, where Abraham and Isaac were said to be buried.* But after David, Tony said, Jerusalem became the holy city and the most revered site. Tony thought this was largely a military development.

Hebron, he said, was indefensible and a lousy place for a king and general to build his capital city. Jerusalem, though, was perfect — high ground, water, just about everything you’d want for a Bronze Age walled city. The only thing it was lacking was some claim to holiness or sacredness that could trump the bones of the patriarchs in Hebron. So, Tony says, David and Joab probably cooked up the idea that the vaguely located “Mount Moriah” from the story of the binding of Isaac in Genesis was the same place as Jerusalem. David purchased land there and built a shrine, literally enshrining the place, and presto — he had a capital city worthy of a warrior-king.

We were there during the First Intifada (which, of course, wasn’t yet called the “first” Intifada) and things were a bit tense in and around Jerusalem. More than a bit, really. Our formal college tour, led by Tony, was unable to take us to several sites because of the uprising or because the IDF had shut them down in suppressing it. We still went to Bethlehem — for Christmas (their Christmas, our Epiphany) — a visit that included multiple military checkpoints and lines of tanks. But Hebron was locked down and our scheduled trip there was cancelled.

But that unrest was, in 1990, kept removed from the Temple Mount. That site was off-limits, held in too great reverence by everyone in the region — Jews, Muslims, Christians, secular scholars — for it to become part of the field of play for the roiling political struggle unfolding throughout the rest of the region. Everyone we spoke to, across the broad array of political and religious perspectives we encountered, said the same thing. It was, at that time, unthinkable to carry that political struggle into the tangled complex of holy places that Moishe Dayan, in 1967, called “all that Vatican.”

This shared sense of keeping that site off limits wasn’t entirely due to religious reverence. It was also a matter of prudence — of a healthy respect for the fact that the Temple Mount is the focus of intense passions and apocalyptic visions for three major religions and, therefore, a powder keg it would be wise to keep safe from sparks. (And I’m sure Tony’s cynical follow-the-money perspective was also a factor. No one wants to scare away the tourists and pilgrims, he said. Everybody needs their money.)

All of that is why it is so frightening to have watched, over the past 25 years, as political violence has seeped into, and then concentrated on, this sacred ground. Hanan Ashrawi — a distinguished scholar, Palestinian legislator, and Anglican — is frightened by this too. “By imposing its own version of its concept of the Temple Mount on the third most holiest Islamic site, Israel is not only provoking the Palestinians, but the entire Muslim world,” she said, warning that politicizing the status of that site seems intended to provoke “a global holy war.”

Ashrawi is a Palestinian partisan, of course, and you’re free to disagree with her passionately partisan framing of the current conflict centered on the Temple Mount. But she’s not wrong about the stakes of that conflict.

The same sense of reverence that insulated that holiest part of the Holy Land from early struggles is driving the current struggle, which is about access to and control of that site. These fireworks in a powder keg are not due to concerns that the inviolable is being violated, or that the Others are desecrating the sacred, but rather about who is permitted and who is denied access to this invaluable holy place — and who gets to decide that.

When I visited the Temple Mount, in 1990, access to the site was shared and negotiated through an arrangement literally named the Status Quo. Nobody seemed completely happy or satisfied with that arrangement, but everyone was able to live with it — and therefore to live with each other. That Status Quo arrangement seems in jeopardy now and, because this holy site is immeasurably important to all sides, that threatens to destabilize far more than just who is able to visit these holy places. So this is one time when I think defending the status quo is both necessary and good.

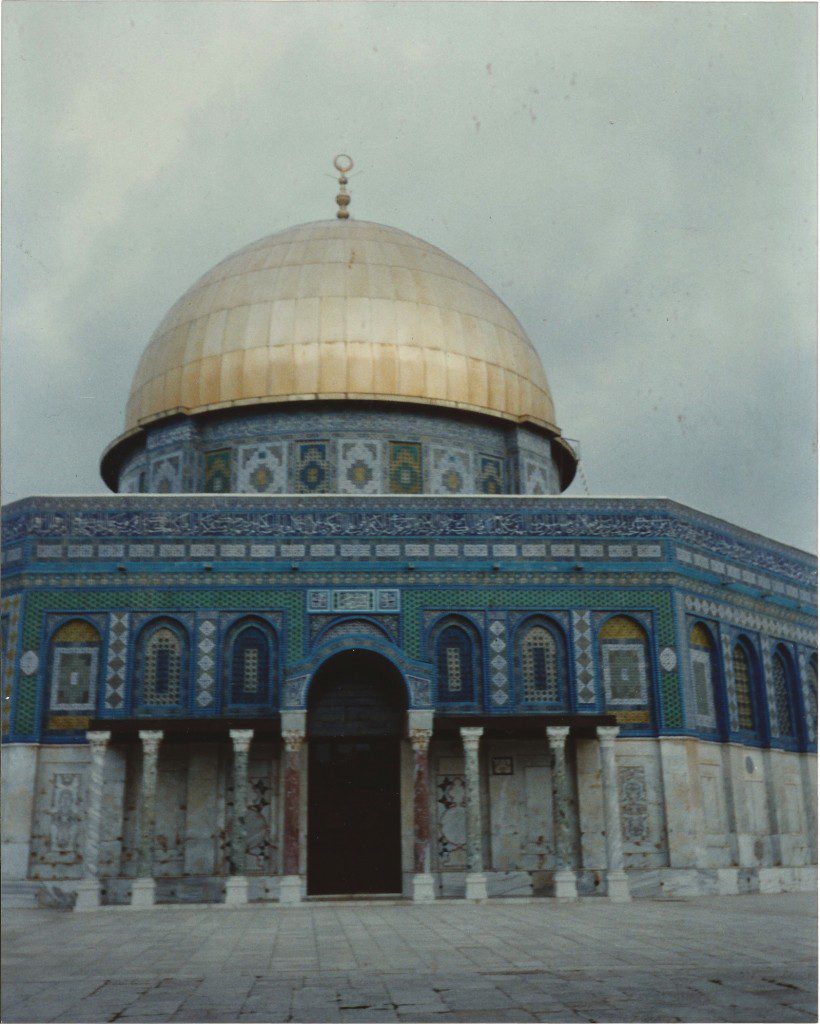

But again, back in 1990, those extreme stakes were not yet on the table. The Temple Mount was off limits to the struggles of that time and the perpetual occupation, the Intifada, and the crackdown against it, did not in any way interfere with our visit to the site. And thus I was able to take this photograph of the Dome of the Rock:

It was a dim, drizzly day and I am a lousy photographer and that photo doesn’t begin to do the building justice. It is dazzling, overwhelming. The inside is awe-inspiring. It took me a moment to close my mouth and remember to breathe. We were instructed to take off our shoes as we entered. I might have done so anyway simply due to the knee-buckling beauty and majesty of the place.

This was not, for me, a religious awe — nothing like the sense I had on the shore of Galilee or among the ancient olive trees of Gethsemane. But I was awestruck nonetheless — by its sheer beauty, by the recognition that I was standing in a place centuries older than my own language, and by a recognition of what that place means and has meant to so many other people. That last one is difficult to describe, but its a tangible, pervasive sense of something like vicarious sacredness — a site that gives meaning to so many for so long is, in turn, given meaning by them, and we can experience a bit of that regardless of whether we share anything like their understanding of the place.

I somewhat glibly referred to this place the other day, expressing my frustration with the way the boilerplate, at this point cliché, description of the al-Aqsa site as “the third-holiest site in Islam,” has morphed from a fact into a factoid. The fact is fuzzily accurate. The factoid is misleading.

Yes, this Islamic holy site is “outranked” by two other sites — sites a non-Muslim like myself would not be allowed to visit, but reciting this kind of ranking amidst a host of other things ranked and rated and quantified sequentially can mislead us into thinking of “third-holiest” as something akin to finishing third in the weekend box office. Like it’s a bronze medal in holiness, or the Ron Paul-in-Iowa of holiness. And that’s not what it means. Not at all. The fact that its “holiness” is exceeded by those two other sites doesn’t in any way diminish its standing as a holy place. Being “third-holiest” does not, as the factoidizing repetition of that designation seems to suggest, mean that Muslims regard the site as anything less than wholly holy.

Consider ∞. Infinity means a number “greater than any assignable quantity or countable number.” But here comes a mathematician telling us about ∞+1. That’s a real thing, but its existence does not thereby make infinity less than infinite. It exceeds infinity, but it does not thereby diminish it.

Part of the problem here is that the word “holy” is nebulous — it can describe both a quality and a category. When we use it to describe a quality, then something can be comparably or relatively “holy” — holy, holier, holiest. And a quality that allows for something to be regarded as “holiest” also seems to allow for something to be regarded as holy-ish — as maybe a little bit holy, but not really. When we use the word “holy” to describe a category it tends to be more binary — either “holy” or not.

Further mucking things up is the confusing way that religions like to use it to mean both things at the same time — the holy of holies, the high holy days, the “third-holiest site,” etc. Thus, for example, it is accurate to say that Yom Kippur is a holier holy day than your average Sabbath. But if you flip that the other way to suggest that the Sabbath is in any way anything less that entirely and utterly holy — that it does not completely belong to the category of holy — then you’re going to run into problems. The “third-holiest” factoid invites similar problems.

But there’s also a real danger in the way this factoid is sometimes employed. In the “Bible prophecy” writings of some white American Christians, al-Aqsa’s status as the third-holiest site in Islam is often contrasted with the Temple Mount’s status as the first-holiest site in Judaism. The implicit — and sometimes explicit — idea there is that Jewish regard for the site therefore outranks its importance in Islam. It seems unfair to have one group’s first-holiest site interfered with by another group’s merely second-runner-up to holiest. And so they ignore the meaning of the fact and recite it as a factoid, twisting a statement that’s actually about the place’s immeasurable value to billions of people into a statement diminishing and dismissing its value to them.

And when I describe that as a real danger I mean exactly that. Tossing lit matches at the powder keg of the Temple Mount is a hobby for “Bible prophecy”-obsessed American Christians. They’re hoping for an explosion. They’re praying for it. They want to see the islamic holy site razed so that the Jewish holy site can be rebuilt so that the Antichrist they long for can come along to desecrate it. And then, they believe, RoboJesus can at last come back, kill the infidels, destroy the whole thing, and replace it with a holy site for them. At which point they win, I guess.

I said earlier that the fact behind this factoid was fuzzily accurate. “Al-Aqsa is the third holiest site in Islam” is an accurate statement, but it contains terms that are defined and understood in different ways by different audiences. Here’s how Gershom Gorenberg addresses this in his excellent, dismayingly insightful book, The End of Days: Fundamentalism and the Struggle for the Temple Mount:

Al-Haram al-Sharif, the Noble Sanctuary, is the third-holiest site in Islam. Near its center stands the Dome of the Rock — a gilded half-sphere rising from an octagonal base. The protuberance of bedrock inside the shrine traditionally marks the spot where Muhammad ascended to heaven on his nighttime journey from Mecca nearly 1,400 years ago. It probably also marks — a shimmering uncertainty is part of the landscape — the location of the Holy of Holies, the sacred core of the Jewish Temple. At the southern end of the esplanade is Al-Aqsa Mosque. To confuse matters, the name has a double meaning: Today any Muslim, at least in Jerusalem and the West Bank and Israel, will insist that the entirety of the Haram is Al-Aqsa, including the open squares between the shrines and the olive grove north of the Dome, all sacred ground.

(The cover of Gorenberg’s book features a splendid photograph of the Dome of the Rock, artfully framed in full sun by David H. Wells. Wells’ photo does a far, far better job than mine in capturing the beauty of the site, but I posted my photo here instead because I stood there and took it myself.)

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* In the book of Acts, Luke has Stephen saying the Cave of the Patriarchs was in Shechem (now Nablus), which is a long way in the other direction from Hebron. Shechem is also near where Tony thought Mount Moriah really was — by which he meant that was the location of the actual mountain referenced in the story, not that he thought the story actually happened.