I know about Koinonia Farm and Clarence Jordan’s cotton-patch socialism, but I know next to nothing about the Delta Cooperative Farm or Providence Farm — two other experiments in Christian socialism and racial justice in the rural South that began years before the Jordans and Englands broke the soil in Americus, Georgia.

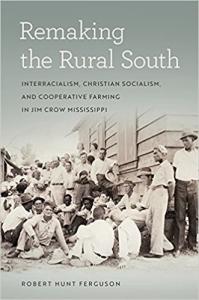

Robert Ferguson explores their stories in his new book, Remaking the Rural South: Interracialism, Christian Socialism, and Cooperative Farming in Jim Crow Mississippi. Ferguson summarizes his book for John Fea’s Author’s Corner series:

Focusing on two interracial, Christian socialist communities in the rural South, the book argues that former sharecroppers and their allies enacted significant cultural shifts that placed their communities in the vanguard of human rights struggles in the 1930s to the 1950s. From the Great Depression to the civil rights movement, residents of Delta Cooperative Farm and Providence Farm acted out moments of modification that created egalitarian, democratic communities and which were ultimately quashed by white massive resistance to the black freedom struggle.

The farms were founded, partly, by Sherwood Eddy, a longtime missionary with first the YMCA and then later with Christian Action. He was, first and foremost, an evangelist, and very much the kind of Bebbington-esque Christian who could be claimed as a part of American evangelicalism.

But then again, “Christian Action” was originally called the Fellowship of Socialist Christians, and was a project largely promoted by Reinhold Niebuhr and others now regarded as “mainline” Protestants. So contemporary white evangelicals might not want to claim him as one of their own.

The Niebuhr connection is intriguing not just because Eddy’s theology seems so much more evangelical than old Reinhold’s, but because Eddy also seems like just the sort of unchastened Rauschenbusch-style progressive that Niebuhr criticized so effectively. Sherwood Eddy seems like a character out of a Charles M. Sheldon novel.

Sheldon was the evangelical Kansas preacher and semi-socialist whose book In His Steps was accidentally never copyrighted, and thus became a Harry-Potter-level publishing phenomenon. That’s the book that gave us the question What Would Jesus Do? That question lives on as a popular evangelical slogan — WWJD? — even though white evangelicals no longer answer it anything like the way Sheldon did. (What Jesus Would Do, Sheldon believed, was democratize the means of production, among other things.)

Ferguson’s title seems a bit overstated. The fine folks at Delta and Providence were clearly hoping and trying to “remake the rural South,” but that ambition was squashed and suppressed within decades. But the possibility of such a remaking — and the possibility of attempting it without awaiting permission from The Powers That Be — is something Ferguson hopes readers will take from his book. As he says:

In times of national polarization, history doesn’t have to be a weight that paralyzes us. We should never look at the world and say, “well, it’s always been that way” and then go about our days weighted down by an ahistorical, erroneous understanding of the past while doing nothing about the present. Rather, history can liberate us when we understand that in the face of overwhelming hardships — such as, say, the Great Depression or Jim Crow — historical actors have posed radical changes and set about achieving those changes.

This inspirational, aspirational use of history can be a Good Thing. It is good to recognize and try to learn from the exceptional heroes of the story. That can be, as Ferguson says, liberating.

But it can also be dangerous. It tempts us to identify with the heroes in the story, to imagine that we’re like them and that we would have played their part had we been in their time and place.

That’s unlikely. And it’s made even less likely the more we indulge the idea that it’s true. The majority of white evangelicals in rural Mississippi were not like Sherwood Eddy. The majority of white evangelicals were those who made up the “massive white resistance” that crushed these experiments in “interracialism, Christian socialism, and cooperative farming.”

It’s good and important to engage in what Donald Dayton called “Discovering an Evangelical Heritage” of radical faith and dedication to justice. But we should read those stories cautiously, keeping in mind that, as Mal Ortberg put it, “I Would Not Have Been Burned as a Witch in the Early Modern Era No Matter What I Would Like to Believe About Myself and Would Have in Fact Been Among the Witch-Burners.”

As we decorate the graves of the just, we mustn’t flatter ourselves by imagining “If we had lived in the days of our ancestors, we would not have taken part with them in shedding the blood of the prophets.”