On the one hand, Benjamin Lay was easy to dismiss. He was an angry, impatient, impertinent radical who employed ridicule and sarcasm. He had a penchant for confrontational theatrical stunts. He was an un-Quakerly Quaker — a pugnacious member of a pacifist sect considered disreputable by mainstream churches. And he was also a hunch-backed dwarf and a cave-dwelling vegetarian.

On the other hand, all of that also made Benjamin Lay very hard to ignore. Benjamin Franklin understood that. Franklin knew a thing or two about publicity and he happily published Lay’s anti-slavery screed because he recognized that this book, and this author, were sure to get people talking.

Franklin published Lay’s book in 1737 — almost 20 years before the abolitionist Quaker John Woolman self-published his own book. The difference between Lay’s and Woolman’s styles can be seen in the titles of their books. Woolman’s somewhat meekly suggested that he had some Considerations on the Keeping of Negroes that he politely requested readers to judge for themselves. Lay, on the other hand, titled his book All Slave-keepers That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates.

If that wasn’t blunt enough, Lay laid it on further in his expansive sub-title: “Pretending to lay Claim to the Pure & Holy Christian Religion; of what Congregation soever; but especially in their Ministers, by whose example the filthy Leprosy and Apostasy is spread far and near; it is a notorious Sin, which many of the true Friends of Christ, and his pure Truth, called Quakers, has been for many Years, and still are concern’d to write and bear Testimony against; as a Practice so gross and hurtful to Religion, and destructive to Government, beyond what Words can set forth, or can be declared of by Men or Angels, and yet lived in by Ministers and Magistrates in America.”

Lay chastises slave-owning ministers and magistrates as impure, unholy, false, filthy, gross, and hurtful apostates. And that’s all before the first page of his text. Phew. That might give you a sense of why he was formally barred from four different Quaker meetings — including one from which he was physically expelled, carried out the door and tossed onto the ground after a stunt in which he stabbed a Bible he’d rigged with fake blood.

Apologists for the slave-trading, slave-keeping American theologians and evangelists of the 18th century always take pains to remind us that they were “men of their time.” Which they of course were, because everyone must be. But Benjamin Lay (1682-1759) was also a man of their time. He was born before and died after Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758). George Whitefield (1710-1770) was not only a man of Benjamin Lay’s time, he and the radical Quaker shared a mutual friend in Ben Franklin.

This is why we sometimes describe people like Benjamin Lay as being “ahead of their time.” Which they of course weren’t, because no one can be. That odd phrase — “ahead of their time” — is sometimes meant as a compliment, but it is also sometimes employed to deny people like Lay the same gracious solicitude we’re eager to bestow on their contemporaries. We tend to be, in other words, more willing to forgive people like Edwards and Whitefield for being disgracefully wrong than we are to forgive people like Benjamin Lay for being defiantly right.

So we read Edwards’ indignant defense of slave-owning ministers and we reflexively rush to explain it away, even though every word of what Edwards argued was wrong. But then we read Lay’s indignant condemnation of slave-owning ministers and we reflexively critique his tone or his approach, even though every word of what Lay argued was, and is, true. Look at the way we treat figures from a century later on and you’ll see the same dynamic at work. Proponents of failed, inadequate compromises and “colonization” schemes are defended, sympathetically, as “men of their time.” Those who were unambiguously right — William Lloyd Garrison may be the most obvious example — are criticized, unsympathetically, as intemperate cranks. We withhold our forgiveness and generosity from them, even though they don’t require our forgiveness — only our thanks.

Fast-forward another half-century and we can find even more examples. We display an instinctive, boundless sympathy for those who faltered and surrendered the unfinished work of Reconstruction while at the same time we offer a kind of harsh, dismissive criticism for those unseemly “radicals” who were steadfastly right both from the perspective of their time and of our own. (“Hindsight is 20/20” we say, with that same weirdly dismissive resentment toward those whose sight and foresight our later hindsight has confirmed to be accurate.)

I think this strange, instinctive reluctance to forgive those who were right when most people were wrong comes partly from a defensible impulse. It arises, in part, from our commendable frustration that these folks were not better able to persuade and convince their contemporaries. And we judge them harshly for that — viewing them with far less grace than we’re eager to extend to the great mass of people who refused to listen or to be persuaded by them.

Maybe more people would have been convinced by Benjamin Lay’s arguments if he hadn’t been so quick to condemn them all as leprous apostates, spraying fake blood all over their pews. Maybe every white person in America would have unanimously cried out, “Yes, you’re so right! I see it now! Let’s end slavery immediately!” if only Garrison hadn’t been so rude as to command their attention by burning copies of the Constitution.

We deplore the tone and the supposedly off-putting anger and impatience of such demonstrations. But, I am sorry to say, we fail to express a similar concern for the conditions that brought about those demonstrations.

That’s a paraphrase from the scripture, from the same Birmingham epistle in which King writes:

I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action;” who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a “more convenient season.”

King wrote that in 1963, which was before my time. Lay and Garrison and Thaddeus Stevens were all, obviously, before my time as well.

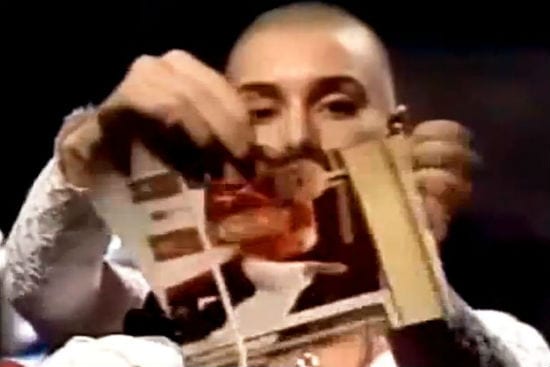

So I want to turn next to an example that is from my time. It’s from 1992, and you can probably guess what it is from the photo above.

This example is why I’ve been using the words “we” and “our” in the hazy, squishy (and, for some readers, inaccurate) way I’ve employed them throughout this post. That use of the first-person pronoun is partly a rhetorical trick — a way of trying to inoculate against a more defensive reaction by including myself, suggesting a tone that is more confessional than condemnatory. But that confessional tone is also necessary, because I personally have much to confess. I have far more in common with the Quakers who carried Benjamin Lay out the door than I have with Lay himself. I don’t want to conscript anyone into that first-person plural pronoun who doesn’t deserve to be included in it, but speaking for myself I can say “We have met the white moderate stumbling block, and he is us.”