Mega-church pastor John MacArthur has died at age 86.

Headlines announcing his death refer to him as a “prominent evangelical” or an “influential evangelical” or, in one case, a “firebrand evangelical,” all of which is inaccurate. MacArthur was prominent and influential and a firebrand, but he was not an “evangelical.” He was a fundamentalist.

That distinction may seem like a fine point here in 2025, but it used to be a very big deal indeed. In fact, this is where the word “evangelical” as it is used today in American Christianity comes from.

Back in the 1950s, Billy Graham was desperate to distinguish himself and his ministry from the negative attitudes and — even more so — the negative connotations and negative perceptions — of fundamentalism. So Billy and those in his orbit rebranded as “Neo-evangelicals.” Billy and Carl Henry and folks at places like Christianity Today and Wheaton College embraced the new term as a way of pointing a finger at fundamentalists and saying, loudly, “We are not that.” It was their way of coming out and being separate from come-ye-out-and-be-ye-separate fundamentalism.

Back in the 1950s, Billy Graham was desperate to distinguish himself and his ministry from the negative attitudes and — even more so — the negative connotations and negative perceptions — of fundamentalism. So Billy and those in his orbit rebranded as “Neo-evangelicals.” Billy and Carl Henry and folks at places like Christianity Today and Wheaton College embraced the new term as a way of pointing a finger at fundamentalists and saying, loudly, “We are not that.” It was their way of coming out and being separate from come-ye-out-and-be-ye-separate fundamentalism.

The “Neo-” prefix dropped away pretty quickly, but the “evangelical” part of the label stuck, and for most of the rest of the 20th century, this is what it meant: “We are evangelicals, as opposed to fundamentalists.”

And for most of the rest of the 20th century, fundamentalists agreed with and appreciated the distinction. You could hear this in a joke I often heard growing up in a fundamentalist church and private school: “An ‘evangelical’ is someone who says to a liberal, ‘I’ll agree to call you a Christian if you agree to call me a scholar.'”

This is why it was a big deal and a cause of great consternation at my church and school when some of us chose to go off to evangelical colleges — places like Wheaton and Houghton and — gasp! — Eastern. These schools were viewed as more insidiously dangerous than Rutgers. That secular state school was regarded as enemy territory — Sodom on the Raritan — but at least there you knew what you were getting into and knew to be on guard. Better the lies of an honest enemy than the pernicious half-truths of those sneaky evangelicals.

I’d be willing to bet John MacArthur repeated and laughed at that joke back in the 1980s. It certainly expressed his opinion of most evangelical seminaries and institutions, which is why he wouldn’t abide having any of his followers attend them, insisting that they attend his own schools instead.

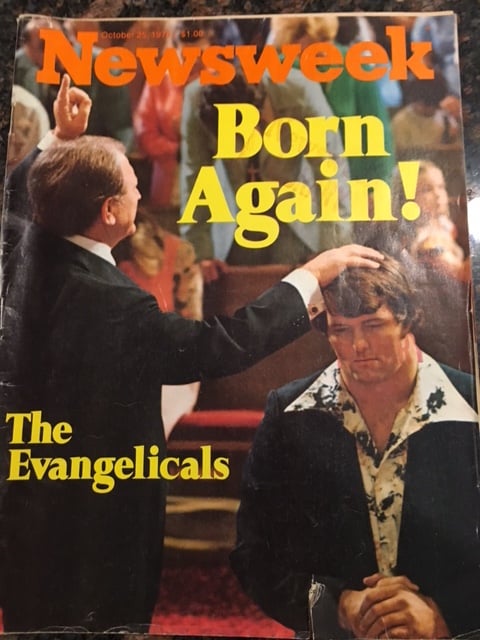

That joke — which I’ve sometimes seen attributed to one of the Bobs Jones — also captures fundies’ resentment of the success of Graham’s “evangelical” rebrand. Graham and other “evangelicals” had achieved a level of cultural acceptance, influence, and even admiration that fundamentalists rejected as worldly compromise, but simultaneously envied. Billy gets his picture taken with presidents and gets to pray at their inaugurations and funerals. Fundamentalists told themselves that this proved he was compromised in a way they never would be, but also it drove them crazy that he got invited to such events and they never did. In 1976, Newsweek ran a cover story proclaiming it the “Year of the Evangelical.” It just wasn’t fair that there’d never be a cover celebrating the “Year of the Fundamentalist.”

The rebranding was, all told, a smashing success. “Evangelical” as then defined — meaning “not like those fundamentalists over there, no sir, none of that” — allowed the new movement to shake off all of the negative connotations and cultural stigma long attached to “fundamentalism.”

That stigma is often exemplified in the example of the Scopes “Monkey” trial of Inherit the Wind fame (or infamy), which has been discussed a bit lately due to the centenary of that event this year.* But decades later, when Billy and friends embraced their “Neo-evangelical” rebrand to escape that association, they were worrying about more contemporary connotations — including the way that white fundamentalism had become the angry face of defending segregation. The Neo-evangelicals were not supporters of the Civil Rights Movement, but Graham recognized that identifying with the uncompromising defense of Jim Crow segregation — as his fundamentalist father-in-law, Nelson Bell, explicitly argued was a white Christian’s biblical duty — would distract from his focus on mass evangelism.

Consider the book Graham’s friend and partner Carl F.H. Henry wrote in 1947, before the group spun off from the rest of fundamentalism to rebrand itself as something else. That book was called The Uneasy Conscience of Modern Fundamentalism, and that was exactly what Henry described — a fundamentalist Christianity that had lost its moral authority because it had lost its moral compass, retreating from public life and failing to address “social ills” including “racial hatred and intolerance.”

This is not in any way to suggest that the “Neo-evangelicals” split away from their fundamentalist roots due to concerns about social justice or Civil Rights or segregation. Far from it. Henry’s main argument was that he and his fellow fundamentalists were correct to have rejected the “heresy” of the Social Gospel, but that perhaps they had taken it a bit too far in rejecting all social engagement and maybe it was time to seek some luke-warm third way so that the wider public might come to perceive them as relevant and as less ungood. But the “uneasy conscience” Henry describes — the moral anxiety — was at the heart of the distinct identity he and Graham would come to carve out as “evangelicalism.” That moral anxiety is the dim semi-recognition that the things we refuse to look at — or to think about or to hear or to learn — might challenge our ability to regard ourselves as the morally distinct and morally superior people beloved and blessed by God. And for white Christians of any kind here in America, that moral anxiety is always about social justice, Civil Rights, segregation, “racial hatred and intolerance.”

One response to this anxiety — this “uneasy conscience” — is to seek to do good. Another response is to seek to be perceived as good. The former leads to repentance. The latter leads to rebranding.

The rebranding was a smashing success on that level as well, assuaging the uneasy conscience and the moral anxiety enough to forestall any urgent need for repentance.

Anyway, by the 1980s, the white fundamentalists who had once been so happy to see those squishy, sophisticated, worldly respect-craving evangelicals depart were now coveting the cultural influence and acceptance enjoyed by those same former kin. And so, into the 1990s and the turn of the century, most fundamentalists followed the road map laid out by Graham and Henry and the rest. They simply stopped calling themselves fundamentalists and started calling themselves evangelicals.

Sometimes this change in branding came with some overly rehearsed indignation as fundamentalists who had, for years, proudly claimed that name as a badge of honor suddenly pretended to be offended when others applied it to them, recoiling as if it were a slur. Sometimes it involved a kind of Orwellian gaslighting, as when Jerry Falwell Sr. began describing Liberty Baptist College as an “evangelical” school and pretending that he’d never said otherwise. In other cases it was more subtle, as in the case of the fightin’ fundamentalists who finished their successful fundamentalist takeover of the Southern Baptist Convention and its seminaries and celebrated the triumph of fundamentalism by phasing out every use of that term.

By the year 2000, every prominent fundamentalist had been rebranded as an evangelical. Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, Tim LaHaye, Al Mohler, John MacArthur, Ken Ham … they were all just “evangelicals” now. And thus “evangelicalism,” as a whole, became more and more like them.

And by this point, the evangelicals who used to be what everyone (including themselves) called “fundamentalists” vastly outnumber the evangelicals of the sort who wanted to be something different and distinct from fundamentalism. Thus, today, “evangelical” no longer means “as opposed to fundamentalist.” It now means “as opposed to Mainline Protestant.” And when given that meaning, every fundamentalist is called an evangelical.

Or, in the case of the late John MacArthur, was called an evangelical.

Hemant Mehta had only just finished writing about the lawsuit filed by a former member of MacArthur’s church — “Woman sues John MacArthur’s church for publicly shaming her for wanting to leave an abusive marriage” — when he had to update that story with the news of MacArthur’s death.

It was a short update. “John MacArthur died on Monday night,” he wrote. “He was a racist, sexist, conspiracy theorist who protected abusers.”

Accurate, but also incomplete. I would add that MacArthur was also an astonishingly arrogant man, while also a remarkably credulous one. He wasn’t a gullible rube about every conspiracy theory, but if the lie was at all flattering to him, he’d fall for it every time, regardless of the source of that lie.

That’s why the last thing I wrote about MacArthur here recommended that he carve out a few hours of time to look at some tentacle porn on 4chan — “John MacArthur and the Anime Death Tentacle Rape Whorehouse.” The title of that post comes from the name of the site where the covid conspiracies MacArthur was promoting originated. I’m sure he didn’t get those ideas directly from his own visits to that horrific cesspool, but that was the source of what he was teaching and I thought it would be instructive and edifying for him to gain a deeper appreciation for the kind of people he was treating as authorities.

MacArthur’s QAnon-adjacent covid denialism put him at odds with public health officials and that, in turn, put him at odds with everything he had previously said and taught about “Romans 13” and “submission to divinely ordained government.” Hobgoblin of small minds and all that.

We also occasionally checked in with MacArthur due to his decades-long war with Pentecostal and charismatic Christians. And we followed along, sometimes with commentary, as Warren Throckmorton tried to make sense of MacArthur’s dubious, weird story about going to the Lorraine Motel right after Martin Luther King Jr. was killed there. That story was fascinating not because everyone else MacArthur claimed was there denies his account, but because he always seemed to imagine that if it was true it would somehow be a lifelong get-out-of-jail-free card, licensing him to spout whatever racist crap he wanted without criticism because he once rode in a car with John Perkins.

Anyway, MacArthur is dead now. He is in the presence of God where he is surely disappointed to learn that the folklore of “Hell” is not true and that God is not at all the kind of Cosmic Monster God would have to be for God to make or want to make such a horrible idea real. I suppose for somebody like MacArthur, the absence of eternal, merciless Hell for other people is something like Hell for him.

* See, for example, this piece from NPR: “100 years after evolution went on trial, the Scopes case still reverberates.” Among those quoted in the piece is Ken Ham, the fundamentalist young-earth “creationist” who runs the Creation Museum and Ark Encounter. Although this report doesn’t do this, Ham is, like MacArthur, frequently identified in the media as an “evangelical.”

That description of Ham would have been inaccurate back in the 1980s, when “evangelical” meant “as opposed to fundamentalist.” Today, when “evangelical” means “as opposed to Mainline Protestant” or, more generally, means “a white, patriarchal, nationalist religious movement made up of Christians who seek power to transform American culture,” it is accurate.

Of course, even going by the (Neo-)original meaning from the 1950s-1970s, things like the Scopes trial or the Ark Encounter were not clearly on one side of the evangelical/fundamentalist boundary. Biology and geology professors at Wheaton College know the science, and understand that guys like Ken Ham are dishonest grifters, but they’re still not allowed to say that out loud in class.