Since some of what I’m about to say will upset some of my white evangelical brethren who think of themselves as traditionalists, let me start out by arguing for the traditionalist side.

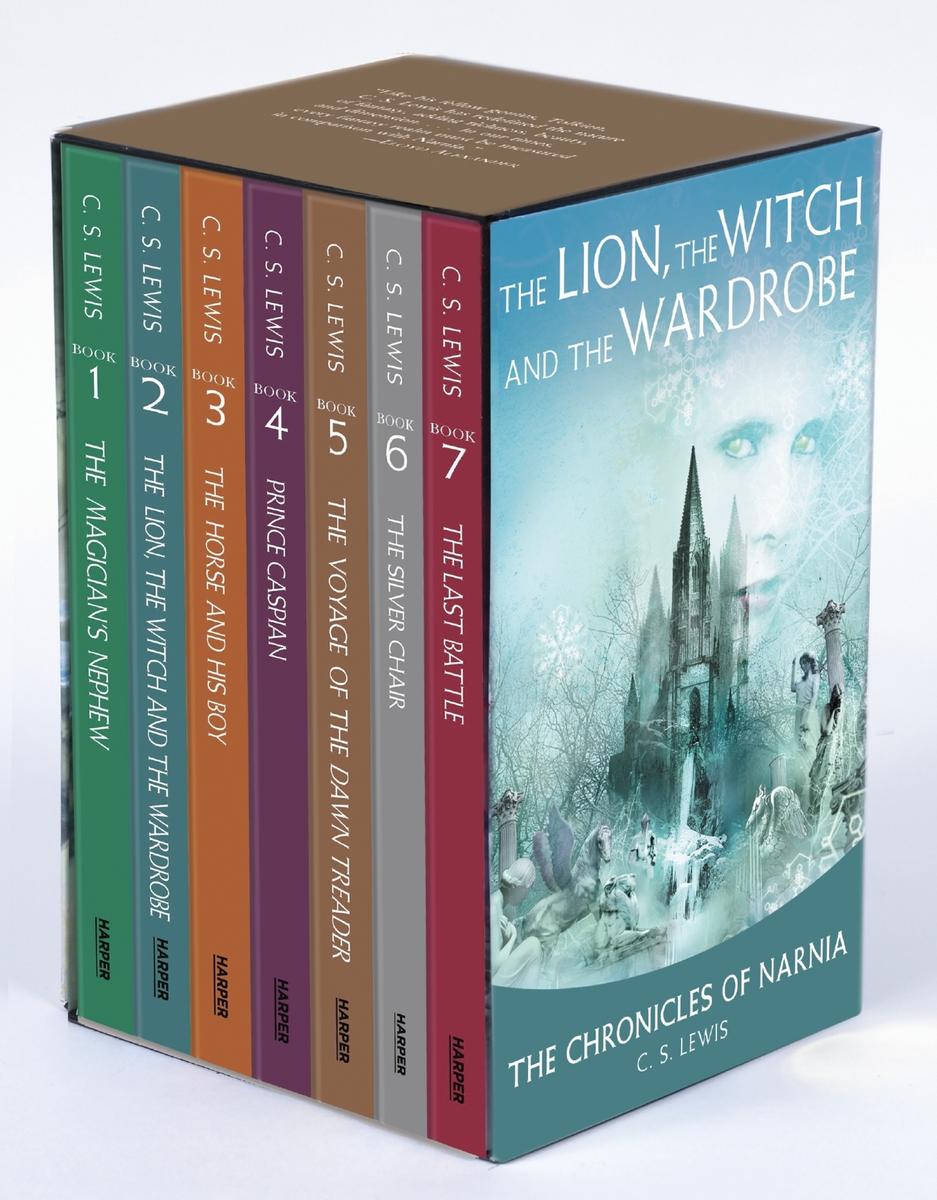

The Chronicles of Narnia should be read in their right and proper order. That means starting with The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe, followed by Prince Caspian, and then The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, The Silver Chair, The Horse and His Boy, The Magician’s Nephew, and finally The Last Battle. This is the correct order and the correct numbering of these books, I through VII.

Some modern editions of this series get this wrong, reshuffling the series into a roughly chronological order. Some publisher decided that since Magician’s Nephew was the “Genesis” of the Narnia books, it should come first, and so they began renumbering the series with that as Book I. I consider this a mistake. This is not how one is meant to read those books. Readers — especially the younger readers for whom the series was intended — are supposed to encounter Narnia for the first time the way that Lucy does, not the way that Jadis does, for goodness’ sake. That’s just wrong.

I am a Narnia traditionalist. I believe the books should be read in the proper order, and that the proper order is the original order — the order in which the books were first written and published.

So far so good. My traditionalist brethren most likely agree with me about this, and since they share my admiration for C.S. Lewis, they probably feel just as strongly about this as I do. If you want to enjoy and understand these books properly, you should read them in the order in which they were composed, not in some supposedly chronological order cobbled together by some editors and publishers long after the fact.

But when I take this same approach to the books of the Bible, these folks begin to get wary. When it comes to the books of the Bible, they’re adamant that the loosely chronological order imposed at a much later date is the proper order, and that attempting to read them in the order in which they were first composed and written is somehow a newfangled, modernist mistake.

I suppose this is partly due to how much more difficult it is to determine the compositional order of the books of the Bible. The order of composition and publication for the Narnia books is well documented and very easy to determine. Those books were first published from 1950 through 1956, so this is still within living memory. First editions of the Narnia books are not cheap, but they’re not impossible to find either. But there’s no such thing as a first edition for any of the books of the Bible, and figuring out who first wrote them, and when, turns out to be a challenging and complicated task.

Fortunately, a great many very smart people have been working hard at that task for generations and now, thanks to all of their work and the evidence they’ve pulled together — and their arguments over that work and that evidence, and their revisions based on those arguments — we have a fairly confident understanding of the original, compositional order of the books of the Bible.

I’m not emphatic about that compositional order in the same way I am about the compositional order of the Narnia books — that this is the right and correct and best and only order in which to read these books. The Narnia series is a short. unified, complementary collection of books in a single genre written by a single author with a single voice. The Bible is none of that. There are many good ways to approach its many different books.

But I do think it is helpful to keep the compositional order in mind when reading any of those books. That helps us understand the context of their composition, and thus their meaning. And it helps us to understand their meaning in relation to one another — to understand who was responding to whom, and whether they were agreeing, or revising, or rebutting the earlier assertions and arguments of the earlier works.

Consider, for example, the passage from Amos quoted here in the previous post: “But let justice roll on like a river, / righteousness like a never-failing stream.”

This is, by our best reckoning, one of the oldest passages in the Bible. The book of Amos is one of the oldest, earliest books written. Some fragments later included in some later books might be older than Amos — things like the Song of Deborah that eventually became part of the book of Judges. But the book of Amos was composed before almost every other book except for maybe the first part of Isaiah (chapters 1-29) and maybe Hosea.

This can be unsettling to think about because we’re accustomed to reading the books of the Bible in their customary order, which starts with Genesis and Exodus, not with Amos and Isaiah. And it seems strange because many books written long after Amos and Isaiah tell stories set long before them. But that strangeness can be illuminating, instructive, and insightful.

The verse from Amos above is followed by a verse that reads, in words attributed to God: “Did you bring me sacrifices and offerings forty years in the wilderness, people of Israel?” We read that and we reflexively think of it as a reference to or a citation of the story in the book of Exodus, but that’s backwards. Amos was written many centuries before the book of Exodus. That much, much later book was written as an exposition on that 40 years in the wilderness first mentioned many generations earlier by the prophet Amos.

Amos has priority — it came first. One fascinating aspect of this priority of Amos and Isaiah is the shared theme of these two prophets when it comes to denouncing religion in the absence of justice. (With justice here meaning what we nowadays refer to with the redundant retronym of “social justice.”) The MLK-famous verse quoted above comes as the climax of one of several anti-religion rants in the book of Amos:

I hate, I despise your religious festivals;

your assemblies are a stench to me.

Even though you bring me burnt offerings and grain offerings,

I will not accept them.

Though you bring choice fellowship offerings,

I will have no regard for them.

Away with the noise of your songs!

I will not listen to the music of your harps.

But let justice roll on like a river,

righteousness like a never-failing stream!

This parallels what we read in the early chapters of Isaiah:

“The multitude of your sacrifices—

what are they to me?” says the Lord.

“I have more than enough of burnt offerings,

of rams and the fat of fattened animals;

I have no pleasure

in the blood of bulls and lambs and goats.

When you come to appear before me,

who has asked this of you,

this trampling of my courts?

Stop bringing meaningless offerings!

Your incense is detestable to me.

New Moons, Sabbaths and convocations—

I cannot bear your worthless assemblies.

Your New Moon feasts and your appointed festivals

I hate with all my being.

They have become a burden to me;

I am weary of bearing them.

When you spread out your hands in prayer,

I hide my eyes from you;

even when you offer many prayers,

I am not listening.

Your hands are full of blood!

Wash and make yourselves clean.

Take your evil deeds out of my sight;

stop doing wrong.

Learn to do right; seek justice.

Defend the oppressed.

Take up the cause of the fatherless;

plead the case of the widow.”

Again, these are among the oldest passages in the Bible. The few fragments that might be older than this are things like the Song of Deborah, which record the words of people about God, but those passages above are the oldest words presented as being from God.

This is the first thing we hear God telling us — the first thing God has to say. Religion without justice is detestable. Worship, praise, prayer, gatherings, festivals, sacrifices, and celebrations are, in the absence of justice for the oppressed and the poor, loathsome and abhorrent to God.

This is the first thing we are told about worship and prayer and and praise and sacrifice. That seems important.

But it also seems confusing.

One instinctive reaction to these first texts is to defend worship, prayer, and religion by noting that God’s first words to us do not necessarily reject any of these things per se, God only says that they are detestable in the context of social injustice. God is saying here that God rejects our prayers and worship because of our injustice and God seems to suggest that these same prayers and worship would be considered differently by God if we corrected that injustice. So we argue that prayer and worship are not bad in and of themselves — that they are Good Things that only become Bad Things if they occur in the bad context of injustice. In proper context — all else being equal (perhaps literally) — God probably loves and desires our prayers, praise, and worship.

This instinctual defense of religion is probably a defensible inference based on the implicit “therefore” or “because of” logic of these passages. But it’s still an inference. A justifiable leap, but still a leap.

And it’s not the main point of either of these passages.

The main point — the very first thing God has to say to us, ever, as far as we know — is not “pray” or “worship,” but rather “Seek justice. Defend the oppressed. Let justice roll on like a river. …”

This is the biblical priority, in every sense of that word. First things first.

(There’s another, far trickier aspect of all of this — something more complicated and confusing about the fact that these passages are the oldest and earliest scriptures about prayer and worship and religion. But given that we’re already 1,000+ words in here, we’ll save that can of worms for another day.)