The Wikipedia entry for the word “prequel” is both a useful explanation of the term and its origins, and a delightfully nerdy example of how Wikipedia is, itself, the product of a community of scrupulous, idiosyncratic enthusiasts. So if you want to know the etymology and meaning of the word, you can read the first half of that page. And if you want a taste of how that term has been endlessly debated in arcane fan forums, or a consideration of how/whether it should be applied to time-travel stories, you can read the second half of that page.

“Prequel” is a pop-culture word that arose in — and is usually mostly applied in — the realms of popular culture, fandom, and genre fiction. The first published use of the word is apparently from a 1958 article in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, used by Anthony Boucher to describe the relationship between two science fiction stories written by James Blish. Blish wrote “Earthman Come Home” in 1955 and then, later, in 1956, wrote a story expanding on that, but set before it, called “They Shall Have Stars.”

“Prequel” is a pop-culture word that arose in — and is usually mostly applied in — the realms of popular culture, fandom, and genre fiction. The first published use of the word is apparently from a 1958 article in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, used by Anthony Boucher to describe the relationship between two science fiction stories written by James Blish. Blish wrote “Earthman Come Home” in 1955 and then, later, in 1956, wrote a story expanding on that, but set before it, called “They Shall Have Stars.”

It’s not clear that Boucher invented the word, as the term “prequel” may have been kicking around in the realm of “fantasy and science fiction” prior to his putting it into print. Christopher Tolkien says that his father, J.R.R. Tolkien, used that word to describe his The Silmarillion years before Boucher’s article. It’s thus possible that C.S. Lewis had heard the word before writing The Magician’s Nephew as a prequel to The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe (the example we discussed here in our previous post on biblical chronologies).

In any case, the word caught on and stuck around because it proved to be useful and necessary. And not only in the realm of fantasy and science fiction.

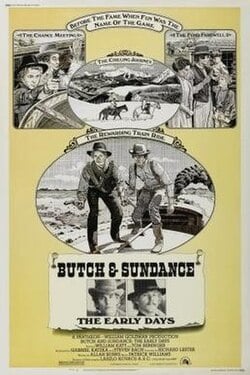

That Wikipedia article notes that the term first became widely known and used after the release of Butch and Sundance: The Early Days, the 1979 follow-up to the beloved 1969 original in which poor Tom Berenger and William Katt were cast as younger versions of the roguish heroes and forced to remind audiences that they were not watching Paul Newman and Robert Redford this time around. (The prequel isn’t a bad movie, and Berenger and Katt are not bad in it. They’re fine. But still, when watching it you can’t help but to keep asking “Who are these guys?” and to realize that you’re just missing Newman and Redford the whole time.)

By the time that the trilogy of Star Wars prequels came out, beginning with the release of The Phantom Menace in 1999, the word prequel was widely used and understood in the general culture.

Because the word is specifically useful, it has even been sometimes applied outside of the sphere of popular culture, genre fiction, and Hollywood movies. As that Wikipedia article notes:

Though the word “prequel” is of recent origin, works fitting this concept existed long before. The Cypria, presupposing hearers’ acquaintance with the events of the Homeric epic, confined itself to what preceded the Iliad, and thus formed a kind of introduction.

The Cypria, alas, is lost to us. But I would suggest that ancient epic was composed due to many of the same motives that gave us things like Butch and Sundance: The Early Days. Audiences loved the Iliad and wanted more of that story and the creator of the Cypria probably did too. The first work was also worth further exploring or explaining, and so subsequent works — some set prior to the original story — were bound to follow.

Prequels and sequels don’t always — or maybe even don’t often — live up to the original works. Sometimes they seem to be little more than an exercise in “Hey, do you guys remember that earlier movie? I loved that movie, wasn’t it great? Man, I sure loved that movie.” For every successful sequel or prequel that enriches and expands on the original there’s an unsuccessful sequel or prequel that seems to undermine it. (For every Godfather 2 there’s a Godfather 3. For every Andor, there’s a Rise of Skywalker.)

But in any case, I think the language and logic of “prequels” can be helpful when thinking about biblical chronology. Or, rather, about biblical chronologies.

Ask a Star Wars fan about the “chronology” of those movies and stories and they will respond by asking you what you mean by “chronology.” Do you mean the chronology of the stories’ creation and publication — their compositional order? Or do you mean the chronology within the stories themselves? (Star Wars fans are particularly clear about this distinction because, after all, this is a collection of stories in which the very first words to appear were “Episode IV.”) They understand the difference between the internal chronology of the stories and the compositional order of the stories. And they understand how this difference shapes the meaning of these stories, highlighting how the multitudes of prequels and sequels both expand on and sometimes alter the previous installments, or how the various stories may be in tension with one another.

No Star Wars fan will let you get away with suggesting that Episode IV: A New Hope was written as a sequel to Rogue One. They’ll be upset by the suggestion not just because it is incorrect, but because that error would change how we should understand and interpret both of those stories.

Bible fandom isn’t nearly as clear about this as Star Wars fandom is. To be fair, that’s partly because the first installment of the Bible came out much, much earlier than 1977, so Bible fans, unlike Star Wars fans, don’t have access to the living memory of the creation of the collection.

For much of Bible fandom, the compositional order of the collection is unknown and unconsidered, and is likely misunderstood. Tell them that the prophets were written as sequels to the books of Moses and they’ll nod along, even though that’s not true and that it misdirects how we ought to be understanding both sets of works. Remind them that Galatians was written well before any of the Gospels and they’ll regard it mostly as a bit of trivia and not as something that should provide insight and guidance into how they read those works or understand the relationship between them.

I suspect this may be related to why Star Wars fans seem more secure in their devotion than many Bible fans seem to be. A passionate Star Wars fan will be happy to spend hours discussing the tensions — the argument — between Last Jedi and Rise of Skywalker. They may disagree with which side of that argument you side with, but they won’t be indignant at the suggestion that one can or should choose a side. But heaven forfend you try to have such a discussion with most Bible fans about, for example, the tensions between Ezra and Jonah. Choose a side in that dispute — or point out to them that they seem to have done so — and Bible fans tend to get angry and defensive.

In any case, the word “prequel” is a useful term not just for genre fandom but for serious biblical study. If I say that something was “retconned in the prequels,” most of the people attending Comic-Con would understand exactly what I mean, but most of the people in church Bible studies would not. They should. It would help.