Here’s another insight from David Bentley Hart that’s been working on me ever since I came across this last summer in the transcript of the Plough’s podcast: “PloughCast 67: David Bentley Hart and the Worship of Mammon.”

Most of this discussion is about Hart’s translation of the New Testament. “There’s something about going to the text itself and becoming responsible for rendering it directly from Greek into English that makes it hard for you not to notice the things that your mind otherwise has gotten in the habit of skating over,” he says. I suspect part of his aim with this new English translation was to trip up other readers to keep them from skating over or skating past the text itself.

Here Hart discusses how the work of translation enriched his understanding of the Sermon on the Mount:

I was made to realize how much of it really just consists in very practical advice for the poor, only for the poor over against the wealthy who because they’re wealthy, are already characterized as more or less wicked. The way in which there’s a figure who appears in the Sermon on the Mount, who’s the wicked man, the evil man, ho poneros, whose presence is almost effaced by normal translations because two of the three times he’s mentioned as ho poneros, the wicked one, many of the standard translations transformed that into evil in the abstract and in the other case, make it sound as if Jesus is talking about the devil, but actually in the Greek, it’s clear that that’s not what’s going on.

He’s talking specifically about those who exploit the poor for profit and who use a corrupt legal system to do so and is giving advice to those he’s preaching to, not at a level of spiritual exhortation, but very much at the level of just practical community organizer advice on how to deal with the man regarding staying out of debt, not getting trapped in an unjust legal system, and not being reduced to penury or slavery.

This is a different category than the “habit of skating over” that develops, the way we become inured to a text due to familiarity. It’s more like the way that the word “justice” was translated out of most of our English New Testaments and replaced with the increasingly not-right word “righteousness.”

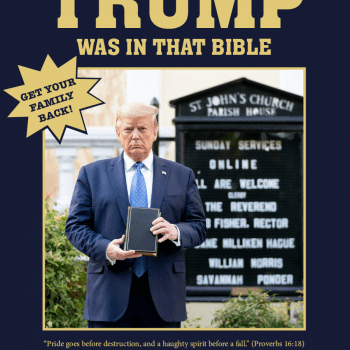

A term that Hart argues means “the wicked man” or “the evil man” gets translated instead as “the wicked one” or “the evil one.” That translation causes readers to assume the text is referring to Satan or “The Devil” and these texts become cornerstones for the construction of a whole theology of Satan. Meanwhile, the wicked man is off the hook. None of the texts indicting him are even regarded as mentioning him any more so he gets away scot free, enabled and empowered to continue exploiting the poor and corrupting justice at every turn.

Hart is trying to fix that. Here, for example, is one of his translations of one famous part of the Sermon on the Mount, the Lord’s Prayer:

Give us our bread today, in a quantity sufficient for the whole of the day. And grant us relief from our debts, to the very degree that we grant relief to those who are indebted to us. And do not bring us to court for trial, but rather rescue us from the wicked man.

That’s from this 2018 article, “A Prayer for the Poor,” in which Hart expanded on what he said to the folks at the Plough:

In the actual text of the Sermon on the Mount, for instance, at least in the original Greek, an ominously archetypal figure, identified simply as “the wicked man” (ὁ πονηρός), makes a brief appearance. He is almost certainly meant to be understood as a depiction of the sort of avaricious, disingenuous, and rapacious man who routinely abuses, deceives, defrauds, and plunders the poor. It is he who ensnares men with false promises wrapped in a haze of preposterously extravagant oaths (Matt 5:37), and he whom Christ forbids his followers to “oppose by force” (Matt 5:39), and he from whom one should request deliverance whenever one comes before God in prayer (Matt 6:13). And yet in most translations—and, more generally, in Christian consciousness—he is all but invisible.

In the first instance, he is usually mistaken for the devil (quite illogically), while in the latter two he is altogether displaced by an abstraction, “evil,” which has no real connection to the original Greek at all. This is a pity. And, really, it is somewhat absurd. Christian tradition has produced few developments more bizarre, for instance, than the transformation of the petitionary phrases of the Lord’s Prayer in Christian thinking—and in Christian translations of scripture—into a series of supplications for absolution of sins, protection against spiritual temptation, and immunity from the threat of “evil.” They are nothing of the kind. They are, quite explicitly, requests for (in order): adequate nourishment, debt relief, avoidance of arraignment before the courts, and rescue from the depredations of powerful but unprincipled men. The prayer as a whole is a prayer for the poor—and for the poor only.

“The wicked man” is a literal translation of the name given to this “ominously archetypal figure” the Gospels describe. But I think a more colloquial translation using 20th-century slang might better communicate the full meaning of this “ho paneros” figure — this “powerful but unprincipled” man, this greedy, dishonest, corrupt, predatory oppressor.

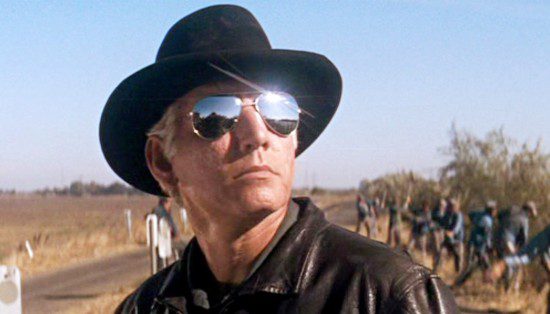

He’s “The Man.” As in the way that Shaft and Cool Hand Luke and Heavenly Blues all used that term.

The Wikipedia entry on this archetypal figure has the unintentionally hilarious, stilted quality of an aging youth minister attempting to employ “with it” slang, but its basic definition still works:

“The Man” is a slang phrase used in the United States to refer to figures of authority, including members of the government. … The phrase “the Man is keeping me down” is commonly used to describe oppression, while the phrase “stick it to the Man” encourages civil resistance to authority figures.

I am going to have to get a copy of Hart’s translation to explore where else “the wicked man” appears in — or has disappeared from — our New Testaments.

Meanwhile, here’s a sense of how our New Testament might strike us differently if we refuse to let the Man be erased from its pages:

• John 17:15, ” I am not asking you to take them out of the world, but I ask you to protect them from the Man.”

• Ephesians 6:16, “In addition to all this, take up the shield of faith, with which you can extinguish all the flaming arrows of the Man.”

• 2 Thessalonians 3:3, “But the Lord is faithful, and he will strengthen you and protect you from the Man.”

• 1 John 5:19, “We know that we are children of God, and that the whole world is under the control of the Man.”