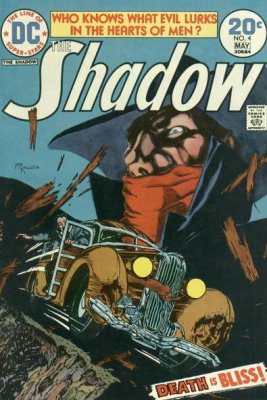

I first met Lamont Cranston on the radio — or, more specifically, on the shelf-full of “Golden Radio Classics” that my dad had on 78 vinyl. I met him again, years later, in the pages of his DC comic. And then again, still later, in seminary, in the works of Niebuhr and Augustine, whose shadowy assessments of human nature echoed Cranston’s signature question: Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men?

(We will not mention here the 1994 movie The Shadow, with Alec Baldwin, having cast it into the same memory hole as the Ben Affleck Daredevil.)

In the old time radio show, that question was always asked and then answered: Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows.

In the old time radio show, that question was always asked and then answered: Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows.

How did he “know” such things? Such knowledge, I am regularly informed by online pedants, could only be the province of “mind-readers” — of people with some paranormal capability of seeing into “the hearts of men.” Absent such supernatural mind-reading powers, they insist, we may never, ever, claim to know — or even to suspect — that evil lurks in any other person’s heart.

Lamont Cranston, these pedants insist, was an uncharitable and uncivil fellow. He failed in his moral duty to give everyone the eternal and inexhaustible benefit of the doubt at all times. He failed the test of the presumption of charity, which they say means that everyone, everywhere should always be assumed to be acting and arguing in good faith. These are the Rules of civility and charity, and these Rules must always be followed.

The first thing we should say in response to such pedants is that they’re misstating, misinterpreting and misapplying those Rules. The presumption of charity is, like the presumption of innocence in a legal proceeding, a starting point, not a mandatory conclusion. A criminal defendant is presumed innocent unless and until proven guilty, but this presumption of innocence does not preclude the possibility of a guilty verdict. It does not mean we must ignore all evidence that points toward guilt or refuse to consider the possibility that this presumed innocence might not withstand logical and factual scrutiny.

We should also note that it is … odd that many of the same pedants insisting that the Rules of civility and charity require an eternal and inexhaustible benefit of the doubt do not disagree with the general assessment of Augustine, Niebuhr and Cranston that “evil lurks in the hearts of men.” They agree, in general terms, that bad faith arguments and disingenuous or unstated motives may exist — that such things are real and perhaps even common. But they disallow any specific evidence to be considered in specific instances and they would forbid any specific conclusions ever be drawn based on such evidence.

Even their favored protestation about “mind-readers” reinforces this general belief. Why would one supposedly need to be a “mind-reader” to draw any conclusions about another person’s motives or good faith? That can only be the case because motive cannot be presumed to be identical to face-value statements of motive — because people’s words do not always accurately represent their intent. This talk of “reading minds” is thus based on the premise that people often argue in bad faith or speak disingenuously — that all people are not at all times wholly trustworthy.

Such mind-reading talk also tends, itself, to be an example of the very “mind-reading” it accuses others of claiming to do. It is leveled as an accusation toward those they say have failed to begin with a presumption of charity:

“Mr. Smith is arguing in bad faith,” says Mr. Jones.

“How do you know that?” the pedants cry. “Are you a mind-reader? You have failed to grant Smith the benefit of the doubt and the presumption of charity!”

Very well, how do they know that? Can they read Jones’ mind to know, with certainty, that his statement about Smith is an uncharitable starting point rather than a reluctant and lamentable conclusion based on evidence? How are they so certain that Jones’ first public statement about Smith was his first-ever thought or consideration?

It would be best, of course, if Jones supplied some of the evidence he is relying on to support his conclusion. It would be best if he said something more like: “I have tried to accept Mr. Smith’s argument in good faith, but X, Y, and Z make that unlikely, and also for that to be true, then A, B, and C would also need to be true, and A, B, and C are not the case. Therefore, I am forced to come to the only available remaining conclusion, which is that Mr. Smith is arguing in bad faith.”

And that brings us to the biggest problem I have with the civility police and the rest of the pedants insisting that we must never, ever acknowledge any specific and demonstrable instance of bad faith. Even that sort of reasonable, evidence-based logical argument will be dismissed by them as a violation of the Rules and a failure to give others the benefit of the doubt or to extend the presumption of charity.

They won’t pay any attention to the matters of X, Y, and Z, or to the possibility that they might raise the reasonable suspicion of bad faith. They will refuse to acknowledge the necessity of A, B, or C for a good faith argument, or to consider the forceful implication of their absence.

And that, in turn, creates some reasonable suspicions about their own good faith, or lack thereof.

Lamont Cranston didn’t actually possess any supernatural ability to peer into the hearts of men. He pretended to — that was part of his shtick and the patter for his act. But he wasn’t actually a mind-reader. He was a detective who explored suspicions based on facts that didn’t fit and then drew logical conclusions based on the evidence he uncovered through investigation.

All those same tools are available to any of us. We may not have Shrevvy, Harry, Margo and a legion of other operatives, informants and assistants to do “leg-work” on our behalf. But we can still gather and examine evidence and draw logical conclusions based on that evidence.

And not only are we capable of doing all of that, we’re obliged to do so. We should certainly grant others the benefit of the doubt and extend the presumption of charity. Start there. Trust … but verify, as someone once said. If something doesn’t add up and we’re given a reasonable reason for suspicion, then “charity” does not preclude us from exploring that suspicion, from gathering and examining evidence.

I’m not saying that everyone needs to adopt the jaundiced suspicion of the old-school newspaper types the corporate chain purged away in the first round of lay-offs ten years ago. “If your mother says she loves you, check it out,” the news desk chief used to say, before he got demoted to copy editing sports agate for applying that principle more than corporate liked.

You needn’t be that suspicious in every day life. Sure, trust your mother — unless or until your mother gives you a good reason not to. But if you have a good reason to be suspicious — based on logic and evidence — then check it out. And when you’re checking it out, you should follow reason and evidence wherever they lead, without predetermining either guilt or innocence as conclusions.

The presumption of innocence and the presumption of charity remain prudent safeguards and valuable, essential principles. We can and should rely on such safeguards to ensure that we do not wrongly convict the innocent, even if that means sometimes being unable to rightly convict the guilty. But these prudent principles do not and cannot mean that we must pretend that everyone is always innocent of everything, that everyone must be eternally and inexhaustibly trusted, and that the hearts of people are always pure and innocent of any bad faith that the evidence suggests may be lurking there.

If we make that the Rule, then we surrender everything to those we allow to argue in bad faith with impunity. They figured that out a long, long time ago, and their ability to exploit this “Rule” unchecked is a big part of why the world is the way it is, rather than something better.

You don’t need a fedora and a red scarf and two smoking pistols to know what evil lurks in the hearts of many. And you don’t need to be a mind-reader. You have Google. You can collect and consider evidence and come to reasonable conclusions about what it makes evident.

The Shadow knows, and we can too