OK, I’m about to need to say some frankly critical things about the Rev. John Hagee, so let me start by saying something nice first. The pastor plays a mean saxophone:

Hagee’s son, Matt, also has a fine voice. (I think he might be happier, and the world might be a better place, if he stepped away from the family business of anti-gay vitriol and “Bible prophecy” nuttery and headed off to Nashville or Branson to follow his musical dreams.)

Anyway, Hemant Mehta directs our attention to John Hagee’s recent appearance on the Trinity Broadcasting Network where, alas, he’s not playing the saxophone. Hagee is, rather, offering what he sees as the evidence that proves his belief in “Bible prophecy.”

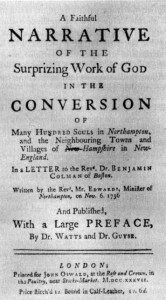

Hagee, you see, is a “Bible prophecy scholar,” just like Tim LaHaye — a premillennial dispensationalist who regards the whole Bible as a series of predictions about the future and the End of Days.

On TBN, Hagee addresses “All the Prophecy Skeptics“:

This is for those of you who are riddled with skepticism about the accuracy of the inerrant Word of God. Only God could orchestrate this. This is a prophetic overlay that I’m about to give you. A prophetic overlay is something that is revealed in the Old Testament and becomes very obviously clear in the New Testament by an exact set of circumstances, but it involved another life centuries later.

Hagee believes the Bible is “inerrant” (excepting, of course, all that stuff in the Bible that says Jesus is the “Word of God”) and that it should be read “literally.” This “prophetic overlay” business is a way of getting around that. It’s his way of telling himself that he’s reading the Bible “literally” while he veers off into allegory.

He goes on to present a series of supposed parallels between the character of Joseph in Genesis (he of the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat) and the character of Jesus in the Gospels. These parallels are strained, to say the least. As Hemant says, Hagee “sounds like he’s reading the (debunked) chain letter about the coincidences between Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy.”

But most of these alleged parallels don’t even rise to the level of coincidences. Hagee’s not wrong when he points out that both Joseph and Jesus had Jewish names, that both had fathers, and that both wore garments. But he is wrong to imagine that these things are worth pointing out.

To be fair, most of the writers of the New Testament also stretched and strained to find echos and allusions for Jesus in the Hebrew scriptures. They found — or invented — some rather creative and imaginative ways to make connections between Jesus and those scriptures. Sometimes that meant tweaking Jesus’ story a bit to better fit the scriptural allusion. Sometimes it meant imposing wholly new meanings on those passages of scripture.

Those New Testament writers — Matthew, Luke, Paul, the author of Hebrews — had a different agenda than Hagee. They weren’t trying to demonstrate the “accuracy” of biblical prophecy. They were making comparisons to teach their readers about Jesus. So unlike Hagee’s “prophetic overlay,” they didn’t just look for parallels, but for points of contrast. They tried to show how Jesus was like David, but also how Jesus was not like David.

John Hagee wants us to see Joseph as a “type” of Jesus — a prophetic precursor “revealed in the Old Testament,” the full meaning of which “becomes very obviously clear” in the prophetic fulfillment of Jesus Christ.

And that is horrifying.

The story of Joseph has been defanged and deformed by Sunday school storybooks and Broadway musicals, but it is not a happy story. Joseph is a predator, not a savior. He is, in this story, an evil, evil bastard.

You probably remember the bit with Joseph’s dreams foretelling seven years of plenty to be followed by seven years of famine, and how that allowed Joseph to store up food during the years of plenty to save the world from starvation during the years of famine. Yay, Joseph! Well done!

Except Joseph saved the world for a price — a very high price. He made the world an offer it could not refuse. Joseph took everything from everyone. He extorted all their money, all their property, and all their land. And when they had nothing left to extort from them, he enslaved them. He didn’t so much save the world, in other words, as he took it over.

Like most of Genesis, this is an origin story. It is the story of where tyrants come from. It is the story of Joseph inventing totalitarian rule:

So Joseph bought all the land of Egypt for Pharaoh. All the Egyptians sold their fields, because the famine was severe upon them; and the land became Pharaoh’s. As for the people, he made slaves of them from one end of Egypt to the other. …

It’s frightening, and probably blasphemous, for John Hagee to claim that Joseph’s tyrannical extortion matches the “exact set of circumstances” that the New Testament presents about Jesus Christ. When Jesus said “Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing,” he was not talking about making slaves from one end of the world to the other. He was talking about this:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to bring good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives

and recovery of sight to the blind,

to let the oppressed go free,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.

Jesus called himself the embodiment of Jubilee. Joseph was the anti-Jubilee.

Even more appalling is the climactic final point in Hagee’s “prophetic overlay.” Joseph, he says, was released from prison “to stand by the side of the most powerful man on the Earth, which was Pharaoh.” That’s just like Jesus, Hagee continues, who was released from the “prison of death” and came “to stand at the right hand of the most powerful person in the universe, God Almighty.”

Hagee’s “prophetic overlay” of Joseph and Jesus thus ends by identifying God with Pharaoh. By presenting Joseph as a “type” of Jesus, he thereby winds up presenting Pharaoh as a “type” of God.

Oy. Not good.

This is particularly weird coming from a guy like John Hagee — a man who is obsessed with “Bible prophecy” and the book of Revelation. The ghost of Pharaoh haunts that book, from the beastly machine that Joseph first invented, to the liberating plagues of divine wrath sent to destroy the thrones of power.

Hagee’s weird little “prophetic overlay” about Joseph and Jesus thus highlights the way his “Bible prophecy” scheme turns the book of Revelation on its head. It portrays God as Pharaoh. It portrays Jesus as Joseph — “saving” the world by enslaving it with lethal coercion.

Like Tim LaHaye and the rest of the PMD “prophecy” crowd, Hagee doesn’t so much believe in a Second Coming as he does in a Second Chance. Like LaHaye, Hagee believes that Jesus got it wrong the first time around with all that proclaiming Jubilee and all that humbling himself unto death, loving your enemies, and all that regrettable inasmuch-as-you’ve-done-it-to-the-least-of-these business. So Hagee longs for a Second Coming in which Jesus returns to get his revenge, to destroy his enemies, ushering in the Millennium in a military coup.

This is how John Hagee’s “Bible prophecy” imagines the Second Coming of Jesus — as a replay of the story of Joseph. No thank you.