From September 2, 2020, “I am a Christian. Here is what I believe about abortion.”

Subsidiarity, mofos.

I want to talk about abortion with my fellow white evangelical Christians.

More specifically, I am addressing those evangelicals who have not sworn their full allegiance to Donald Trump. We might refer to this group as the “19 percent” — meaning the minority of white evangelicals who did not vote to elect Trump in 2016, but I am hopeful that the share of those willing to read or to listen here will be somewhat larger than that.

We might describe my intended audience here as a spectrum ranging from Michael Wear to Russell Moore, which is to say those of my fellow American evangelical Christians who are Trump-resistant or at least somewhat Trump-reluctant. Some of you are emphatically opposed to Trump while others may be ruefully supportive of him due primarily to his support for judges and policies more likely to end legal abortion.

Wherever you fall on that spectrum, you and I disagree on the meaning and the morality of abortion. This post is not an exercise in persuasion or in condemnation. Nor does it involve the suggestion of any sort of compromise or “middle ground” or “third way.” All I want to do here is to explain, as simply and clearly as I can, what it is that I believe about abortion and what the political implications of that are for me.

The difference between what I believe and what you believe is, in some ways, a lot smaller than you might imagine. The implications of that difference expand outward, producing very different responsibilities and obligations for the law, for citizens, and for all of civil society — including the church.

Here is that difference: You believe that full human personhood begins at the moment of conception, which is to say that a fetus, an embryo, a blastocyst, a zygote possesses an equal moral standing to that of any child or adult. To end a pregnancy, therefore, is to take a human life — an act indistinct from taking the life of any other child or adult.

I do not believe that. I make a distinction between the potential human personhood of a fetus/embryo/blastocyst/zygote and the actual human personhood of actual infants, children, and adults. I believe that potential human personhood has great value and great moral significance, but not as great as that of any and every actual human person. Abortion is a serious and significant matter, but it is not at all like “murder.”

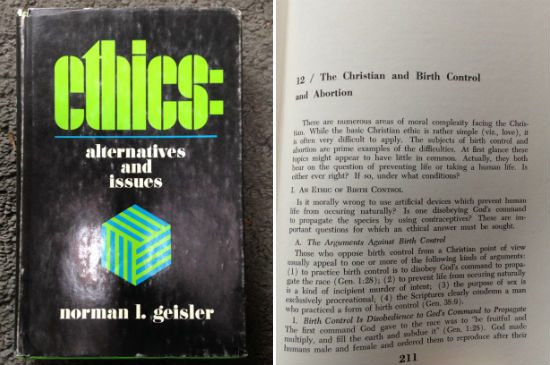

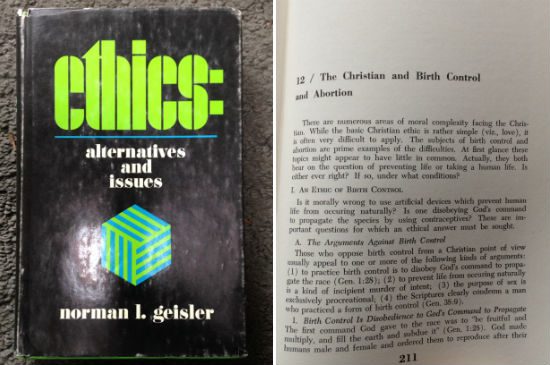

The prolific evangelical apologetics writer Norman Geisler put it this way:

The one clear thing which the Scriptures indicate about abortion is that it is not the same as murder. … Murder is a man-initiated activity of taking an actual human life. Artificial abortion is a humanly initiated process which results in the taking of a potential human life. Such abortion is not murder, because the embryo is not fully human — it is an undeveloped person.

That distinction, which Geisler argued was derived from biblical teaching and biblical prooftexts, led him to conclude that abortion was justified and even obligated in some cases:

When it is a clear-cut case of either taking the life of the unborn baby or letting the mother die, then abortion is called for. An actual life (the mother) is of more intrinsic value than a potential life (the unborn). The mother is a fully developed human; the baby is an undeveloped human. And an actually developed human is better than one which has the potential for full humanity but has not yet developed. Being fully human is a higher value than the mere possibility of becoming fully human. For what is has more value than what may be. …

Birth is not morally necessitated without consent. No woman should be forced to carry a child if she did not consent to intercourse. A violent intrusion into a woman’s womb does not bring with it a moral birthright for the embryo. The mother has a right to refuse that her body be used as an object of sexual intrusion. The violation of her honor and personhood was enough evil without compounding her plight by forcing an unwanted child on her besides. … the right of the potential life (the embryo) is overshadowed by the right of the actual life of the mother. The rights to life, health, and self-determination — i.e., the rights to personhood — of the fully human mother take precedence over that of the potentially human embryo.

The crucial point here is that final sentence, so let me repeat it: “The rights to life, health, and self-determination — i.e., the rights to personhood — of the fully human mother take precedence over that of the potentially human embryo.”

Please note what this does not say or mean or imply or entail: It does not mean that the potentially human embryo has no rights, or no value, or no meaning, or no significance, or no dignity. To regard “the potentially human embryo” as meaningless or worthless would be wrong — wrong both in the sense of immoral and in the sense of inaccurate.

How, then, ought we to account for and to honor the moral claims and moral value of the potential personhood of the unborn? How do we, as you all often say, “protect the unborn”?

The problem with that question is the word “we.” Who is we?

That is always an essential question in Christian ethical teaching and Christian political thought: “Who is ‘we’?” And the way that Christians, for centuries, have tried to answer that question — to clarify and differentiate all of the potential meanings of “we” — fall under the heading of subsidiarity.

Subsidiarity is both a prudential principle and an ethical one. To violate or to reject subsidiarity, then, is both immoral and ineffective. Subsidiarity clarifies the varied and various roles that different people, different actors, different institutions and agencies have — the varied and various responsibilities and obligations we all share in different and differing capacities. It describes what the epistle calls the “inescapable network of mutuality” that binds us all together directly and indirectly. Our various places and roles in that network shape our various responsibilities and duties to one another. To abdicate the responsibilities that are rightly ours, or to usurp the responsibilities that are not rightly ours, is both imprudent and immoral.

Subsidiarity teaches that those closest to a given situation have the greatest responsibility for that situation. Every other actor and agency in the network of mutuality also bears responsibility, but their indirect responsibility takes the shape of supporting those closest, who hold the primary and most direct responsibility.

I believe in subsidiarity. It seems clear to me that the primary responsibility for “protecting the unborn” is given to those whose bodies are literally transforming for that very purpose, which is to say with the actual human persons, the women* whose bodies are carrying and have carried every potential human person who has ever later been born. They are the most direct actors here, exponentially closer and more responsible than anyone else, and the responsibility and obligation of everyone else is to ensure they have all the moral and material support they require to fulfill that role.

I trust those women. I trust them more than any indirectly responsible actor who would trample on their subsidiary obligations by trying to usurp the responsibilities entrusted to those women by nature and nature’s God.

Will 100% of those women make 100% of the best choices 100% of the time? Of course not. They are, like all of us, human, and no human or group of humans is ever always capable of always making only the very best choices. But their humanity is all the more reason to affirm their agency and dignity to choose, not a license to strip them of that humanity by stripping them of their responsibility, dignity, agency, and freedom.

It is not my job — not my ethical duty nor my capacity — to usurp their primacy here. Not as their neighbor, not as their relative, not as their congressional representative or as their pastor or as their president or as their appellate-court judge. Every other actor, agency, institution, civil society organization, magistrate, and pastor does have an indirect role to play — the role of supporting these women to make the best choices and to have the best choices available to them.

What does that mean in practical terms? It means, for most of us, working to create a context for their choices in which they are never constrained by desperation or duress, by the market-worshipping coercion of penury, by fear or want or threat. It means working to establish a context in which financial support, vocational opportunity, human potential, human thriving and human dignity are not contingent or conditional or inconstant. It means creating a context which is hospitable to welcoming new life, and therefore a context in which the choice of hospitality is possible and promising. (If I were to choose a text for a sermon on the politics of abortion, it would be the story of Elijah and the widow of Zarephath.)

Sometimes, when I describe this role and this obligation, those who wish only to deny subsidiarity by a top-down decree criminalizing all abortion will accuse me of just trying to change the subject. But this is the subject. Subsidiarity teaches me that what is best for “the unborn” will be what is best for their mothers. The only way to “protect the unborn” is by protecting those carrying them — protecting their health, dignity, wellbeing, financial security, agency, and freedom.

My uncle was an obstetrician in the 1960s. He was hired to reform a regional hospital in central Pennsylvania that was struggling with one of the worst infant mortality rates in the state. He took the job only on the condition that he could, instead, address the crisis that hospital hadn’t recognized — that it also had one of the worst maternal mortality rates in the nation. Some thought that he, too, was trying to change the subject, but he insisted that if they took better care of those mothers, the infant mortality problem would also be resolved. And it was.

If “we” want to “protect the unborn” then “we” must trust those entrusted with that duty. Erasing or outlawing their central role, their humanity, and their agency is both imprudent and immoral. “We” — for any given value of “we” — need to center them, support them, and provide for them a larger context in which they are best able and equipped to do what is best for themselves and for those potential and actual human persons in their care.

This is what I believe. This is my “abortion politics.” The sectarian nuance and the detailed working out of this may vary somewhat, but this is, in broad terms, what tens of millions of other American Christians who are also Democratic voters also believe.

Again, I am not telling you this in an effort to persuade or to convince. I have done that elsewhere and will do it again, but that’s not what this post is about. I am not here attempting to create any compromise or debate and would not welcome either one. (Although I’m sure the DEBATEME!-boi reply guys will still show up in comments, because fish gotta swim.)

I am telling you this only because I think it is something you should know. What you decide to do with that knowledge, what you feel you’re allowed to do with that knowledge, I leave up to you.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – –

* Mostly women, but not only women. That needs to be said here, for accuracy’s sake and not for the sake of what many of my fellow evangelicals might dismiss as “political correctness.”