Deeply felt spirituality. Who wouldn’t want that? Reckless abandon. Religious ecstasy, even.

Deeply felt spirituality. Who wouldn’t want that? Reckless abandon. Religious ecstasy, even.

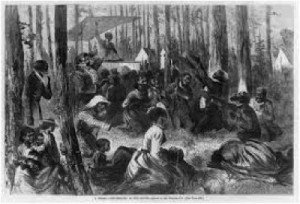

This sensibility lies at the heart of the American religious experience. During the most famous American camp meeting, the Cane Ridge Revival of 1801, one observer looked on in amazement:

To see those proud young gentlemen and young ladies, dressed in their silks, jewelry, and prunella, from top to toe, take the jerks, would often excite my risibilities. The first jerk or so, you would see their fine bonnets, caps, and combs fly; and so sudden would be the jerking of the head that their long loose hair would crack almost as loud as a wagoner’s whip.*

My wife, Priscilla Pope-Levison, whose book Building the Old Time Religion will be out this fall, has told me the dirty little secret that after many revivals—nine months later to be exact—a whole lot of women who attended those revivals gave birth. Evidently, more than just bonnets, caps, and combs came flying off.

Religious ecstasy can be enthralling. No doubt about it. But ecstasy requires restraint, serious restraint. Careful safeguards. The early Pentecostals, a hundred years ago, knew this, according to Grant Wacker, author of Heaven Below: Early Pentecostals and American Culture. When women were slain in the spirit on stage and fell flat on their backs, women came from stage left and stage right to tidy dresses, tugging them below the knee, in the service of modesty.

Great Christian leaders in our day know this, too. During my college years, before the invention of cell phones, one of America’s renowned preachers (no, not Billy Graham) told us he always carried a quarter in his pocket. As soon as he was done preaching, he called his wife. Right away, in fact, because the high of preaching was too much like the high of sex, and he worried that he would give way to sexual, rather than religious, passion. Apparently, one day he did. Where’s a quarter when you need one?

Pentecost, the mother of all revivals, had restraint built in: Jesus’ followers spoke not in tongues but in other tongues. And those tongues, those dialects, had clear content: the praiseworthy acts of God (Acts 2:1-13). The Galilean farmers and fishermen were not unbridled in their ecstasy; the tomb-visiting women did not have hair that cracked like a wagoner’s whip.

Still, how heady it must have been when foreign languages flowed from their spirit-filled mouths. How giddy they must have become when millions of goose bumps erupted when 3,000 bodies were baptized on the spot. How did the apostles respond? What did Jesus’ followers do? They immediately put in place safeguards, communal disciplines that whisked attention away from the fervor and fever of those exhilarating first days.

“They devoted themselves,” Luke tells us, “to the apostles’ teaching and fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers” (Acts 2:42). After Pentecost, they studied. They prayed. They made sure to eat, probably in imitation of Jesus’ last meal, when he broke bread in the upper room. And they did all of this together in uncommon unity.

To top it off, the early church took the tough step of pooling resources (Acts 2:43-47). Remember that many new believers had come to Jerusalem for festivals, including Pentecost, so they were transients; they were homeless. To survive as a community, people sold possessions and pooled them, distributing to people according to their needs.

Some time ago, a student lingered after class to talk. She told me she was part of a quiet revival on campus. She was praying constantly, involved in physical healings, listening for promptings that would lead her to other people—and she was exhausted. As her composure crumbled and tears rolled down her cheeks, she confided that she wasn’t studying or eating well—two of the practices of the early church after Pentecost. So I asked her to write to me twice a week. About what? Not about healings or promptings or ecstatic experiences. About what then? About how many hours she slept, how many meals she ate with friends, how her studies were going. Safeguards. Basic disciplines. Simple practices to preserve religious ecstasy, yes, but also to channel it into a spirituality for the long haul.

My advice for those of us (and I am among them) who want to experience religious ecstasy and a spirituality that overwhelms us? Put disciplines in place. Individual ones. Communal ones, too. And remember always, in one way or another, to keep a quarter in your pocket.

Notes

*Autobiography of Peter Cartwright: The Backwoods Preacher, edited by William Peter Strickland (Hitchcock and Walden; Nelson and Phillips, 1856), pp. 48–49.