With Hurricane Harvey barreling down on the Texas coast, with Galvestonians and Houstonians making their exodus north, I’m struck by the irony of this week’s lectionary text. The focus? The Nile River, which was famous for the floods that fueled the fertility of the famed Nile River Valley and fed the Nile delta.

With Hurricane Harvey barreling down on the Texas coast, with Galvestonians and Houstonians making their exodus north, I’m struck by the irony of this week’s lectionary text. The focus? The Nile River, which was famous for the floods that fueled the fertility of the famed Nile River Valley and fed the Nile delta.

Many of the good people of St. Paul’s United Methodist Church, who support the podcast that accompanies this post, are on their way north, fleeing the coast. Maybe some of them will listen in their cars. Others will be worried about where to stay, what will come of their homes, what next week will look like along the Texas coast.

In the news over the weekend, we will hear of hurricane heroes. Unnamed men and women, children, too, I imagine, who do remarkable things for other people, for strangers, for the desolate and destitute. I imagine, too, that some of those heroes will be undocumented workers, refugees, babysitters, Wal-Mart clerks, and MacDonald’s cooks.

In today’s lectionary, with the exception of a princess—though she has her own story to tell—these are the heroes who change the shape of history.

Moses’ mother

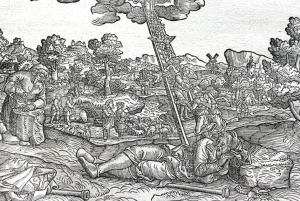

The first is Moses’ mother. Charged to kill her child by throwing him into the Nile River (Pharaoh in the story is hardly imaginative) she does precisely that—almost. She does put her child into the Nile but only after she has built him a miniature Noah’s ark, sealed with pitch, a small basket-boat that will save his young life and change the world as we know it.

Moses’ mother simultaneously obeyed and resisted. She embodied what Martin Luther King Jr. called creative maladjustment. Pinned in by a politics of oppression, Moses’ mother resisted while complying. This is the option available to the oppressed in the midst of a harsh, unyielding powerful nation.

We should not despise them for their creative maladjustment. We should applaud them.

Moses’ sister

Like mother, like daughter. Moses’ sister followed her baby brother along the Nile until she could see he was well cared for. Such daring. Such mettle. No badge of courage for Miriam. No trophy for participation. Just the sort of temerity that would lead her, one day, to dance and sing on the opposite side of the Sea, with the Egyptian army thrown into disarray.

Pharaoh’s daughter

A woman of privilege, if not freedom, Pharaoh’s daughter lifts the baby from his basket and takes him home, where she raises him under the nose of Pharaoh. Courage can find a home among the elite, this story tells us.

The bathing princess took pity on the baby when she heard him cry. This Hebrew word is used of sparing someone in battle. Pharaoh’s daughter spared Moses. Why? Because he cried.

In short order, just a chapter or two later in the book of Exodus, we will learn that God responded to Israel because Israel cried. “I have observed the misery of my people who are in Egypt,” God tells Moses. “I have heard their cry on account of their taskmasters. Indeed, I know their sufferings, and I have come down to deliver them from the Egyptians” (Exodus 3:7-8).

Interesting, isn’t it, to notice the parallel between the words of God and the work of this woman? Who presages the power of God? An Egyptian princess. An outsider. A foreigner foreshadows the act of God.

The midwives

Finally, the midwives. Triply oppressed.

- Foreigners.

- Women.

- Women without children in a culture that accorded status based upon childbearing.

Pharaoh commands the midwives to kill all Israelite baby boys.

They don’t. They won’t.

Instead they offer the sort of resistance to power that most of us can only imagine. They lie to Pharaoh. In fact, they put the lie to Pharaoh’s pretense to power.

They tell Pharaoh that Israelite women aren’t dainty, like Egyptian ones. They pop those buggers out before the midwives can get there and throw the newborns into the river.

With this wonderful lie, they show the ignorance of those in power. Pharaoh, the son of God, the ruler of a massive and magnificent empire, hasn’t got a clue how babies get born. Otherwise, he would have thrown a fit—or the book at them. He doesn’t need to know; he’s busy making the world run.

So the midwives lie—and put the lie to his knowledge. He may know how to run an empire, but he has never experienced a baby drop into his palms.

Creative maladjustment. Again.

Hurricane heroes

Those who hold the power do not need to be creative. Only those who wish to wrest power from them do. And in this story, the creatively maladjusted are women, all of them. Many are slave women. Some are slave women who could not even produce their own babies so were forced to deliver others’.

These are the heroes of the story. The compassionate elite. The refugees. The refuse. The slave-women.