I owe Charles Leland an apology. For years I have thought about him as an embarrassment. But we owe so much to him. He wrote possibly the earliest book treating Witchcraft seriously as a religion, and for that he has been branded as either gullible or a fraud. As I revisit his life I’m delighted to discover a sophisticated and generous man whose work encompassed a great deal more than the one book everyone remembers.

Discovering Leland

For those who haven’t heard his name before, Leland published Aradia, Gospel of the Witches in 1899. Leland reported that his informant Maddalena provided him with the manuscript in Italian which he translated into English. The manuscript contains poems and spells used by Italian strega or Witches. Aradia is one of the source books of today’s Witchcraft, giving us the very name of our Goddess.

I first read Aradia as a young Witch. I was thrilled to discover a remnant of European Folk Religion. I related to Aradia as my own savior, the daughter of Diana sent to teach us the ways of Witchcraft. I memorized the poems and chanted to the moon:

Lovely Goddess of the bow!

Lovely Goddess of the arrows!

Of all hounds and of all hunting

Thou who wakest in starry heaven

When the sun is sunk in slumber

Thou with moon upon thy forehead,

Who the chase by night preferest

Unto hunting in the daylight,

With thy nymphs unto the music

Of the horn-thyself the huntress,

And most powerful: I pray thee

Think, although but for an instant

Upon us who pray unto thee!

As I grew more scholarly I learned that it was naïve of me to take his work at face value. Sober academics doubted that any such survival of Italian Witchcraft existed. Maddalena could have fabricated the manuscript for money, or Leland himself could have fabricated it for fame. Intelligent Witches with good will reasoned that whatever the origin of the manuscript, our own practice proved its value to us.

Practitioners have started to push back against this dismissive skepticism. In his 2020 book Aradia, A Modern Guide to Charles Godfrey Leland’s Gospel of the Witches, Craig Spencer notes mildly that we can also entertain the idea that Maddalena did give the manuscript to Leland and it did document a practice of Witchcraft.

Spencer provides his own translation of the Italian manuscript. He points out places where Roman Catholicism has affected the text as we would expect to find in that kind of material, and notes that Leland didn’t make a fuss about this, which argues for authenticity. Spencer explores the theology of the text and contextualizes the practices. In his own contributions he moves the text forward, in particular exploring the God of the Witches, translating the Lucifer of the text to Apollo and Cernunnos. His book is the productive result of taking the work itself seriously.

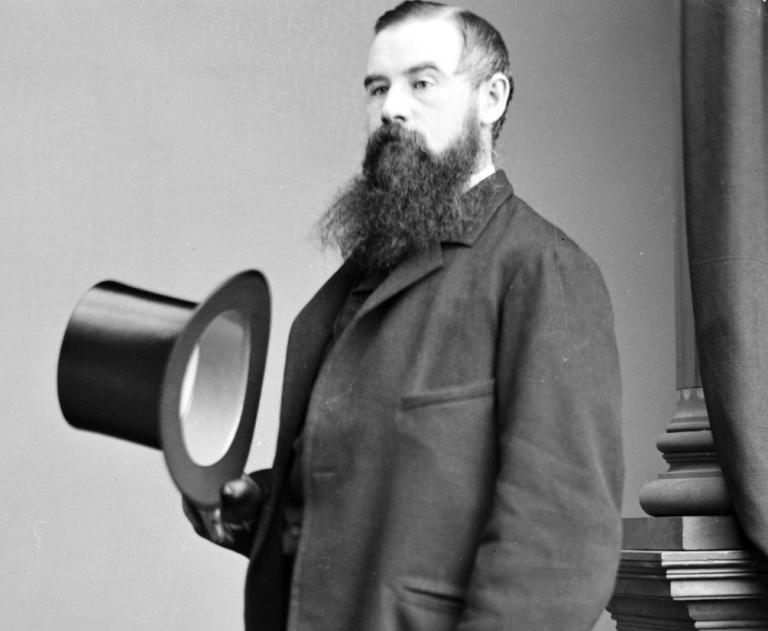

Spencer’s work encouraged me to re-evaluate Leland. He was a man of many accomplishments who was well respected in his time. He practiced law, edited magazines, and founded an art school, which was expected to be his legacy. He wrote a prodigious number of books on a variety of topics: industrial crafts, travelogues, biographies, collections of Algonquin and Gypsy stories, and more than one collection of Florentine Witchcraft.

Leland’s Life

His own memoire is augmented by the biography written by his niece after his death. Elizabeth Robins Pennell is charming in her own right. She moved to London with and her husband Joseph Pennell and spent most of her life there. Like her uncle she was a journalist and writer, writing biographies of Mary Wollstonecraft and Whistler. Her two-volume biography of Leland’s life reproduces his letters to her and others and gives a detailed and intimate portrait of the uncle she called “the Rye”.

Pennell gives us insight into Leland’s life. Born in 1824, Leland grew up in Philadelphia, that Quaker city which had been shaped by Ben Franklin’s intellect and generosity. Even as a child Leland collected folklore. He talked with the Native American laborers on his uncle’s farm, Irish women in the kitchen chatting about fairies, black women quietly mentioning Voodoo. His mother’s friends told him stories of the earliest Swedish colony in Philadelphia populated by Witches who flew on brooms.

He did a youthful tour of Europe before returning to the family to make a living. He lived through the Civil War, editing a Republican magazine arguing for emancipation, and saw men weeping in the streets of Philadelphia the day after Lincoln was assassinated. When Leland inherited his father’s estate he moved to Europe permanently and dedicated himself to the study of folklore.

Pennell spends some pages describing Leland’s life in Florence in “an atmosphere of Witchcraft”. Leland describes meeting Maddalena:

…a young woman who would have been taken for a Gypsy in England, but in whose face, in Italy, I soon learned to know the antique Etruscan, with its strange mysteries, to which was added the indefinable glance of the Witch. She was from the Romagna Toscana , born in the heart of its unsurpassingly wild and romantic scenery, amid cliffs, headlong torrents, forests, and old legendary castles. I did not gather all the facts for a long time, but gradually found that she was of a witch family, or one whose members had, from time immemorial, told fortunes, repeated ancient legends, gathered incantations and learned how to intone them, prepared enchanted medicines, philtres, or spells. As a girl, her witch grandmother, aunt, and especially her stepmother brought her up to believe in her destiny as a sorceress, and taught her in the forests, afar from human ear, to chant in strange prescribed tones, incantations or evocations to the ancient gods of Italy, under names but little changed…

Pennell adds: “When Maddalena was in Florence, the Rye saw her constantly…She introduced the Rye to other witches and women endowed with strange power.”

Leland connected the legends these women recounted to him with Etruscan stories, linking present practices to the Pagan past. He was a regular presenter at folklore conferences and his papers were published in their proceedings. However the zeitgeist has changed several times in the century since he published. While scholars in Leland’s time sought connections and ancient origins, modernism valued the new at the expense of what had come before, and post-modern deconstruction specifically dismantled connections and challenged meaning altogether. In those contexts Leland’s somewhat romantic work fell out of favor.

Reconnecting with Leland

In recent decades a new appreciation for connection has been emerging. We understand culture as less sharply defined. We’ve come to understand that no worldview is entirely dismantled, that each new culture layers atop what came before. In particular we can consider a nineteenth century story in the context of the history of the place where it was found.

In his introduction to Aradia Leland makes several points that seem up to date today. He notes “…witch-lore is hidden with most scrupulous care from all save a very few in Italy, just as it is among the Chippeway Medas or the Black Voodoo.” The Pagan and magical communities today have only recently begun to note the impact of racism on native people and people of color. I am aware of two tribes in which native religion was carefully hidden and has only begun to re-emerge since the passage of the Native American Religious Freedom Act in 1978. When I was writing White Light, Black Magic, Racism in Esoteric Thought I became aware that Hoodoo and Voodoo practitioners still hold conversations in parts of the internet limited to people of color only. Both native and black practitioners have asked white and settler people to respect their autonomy and forgo trying to push our way in to learn what they know. Leland was aware of this dynamic a century and a quarter ago.

Leland did not say that he had been initiated as a Witch or that he practiced Witchcraft. However a careful reading of his biography and his work reveals a sophisticated understanding of magic. He reported that he had precognitive dreams, he used incantations to get himself out of tight spots, he cherished talismans like stones with holes. His work The Mystic Will, published in 1907 after his death, is as clear and helpful as any ceremonial magick writing on developing visualization, memory, concentration, and the ability to manifest results. “All that Man has ever attributed to an Invisible World without, lies, in fact, within him, and the magic key which will confer the faculty of sight and the power to conquer is the Will.”

Returning to Leland is like discovering that your grandfather is actually cool. He’s arguably the grandfather of Witchcraft. He stood up for Witchcraft at a time when it was lumped together with superstition and heresy. He argued for respect and challenged descriptions of Witchcraft which ridicule practitioners and take cheap shots at the practice as vulgar and false. It’s not, he says; it’s worthwhile in itself.

In the preface to Aradia Leland says:

“Witchcraft is all rubbish, or something worse,” said the old writers, “and therefore all books about it are nothing better.” I sincerely trust, however, that these pages may fall into the hands of at least a few who will think better of them.

They have.