We’re learning about ancient history in homeschooling this year.

We don’t have a textbook; I just check books out of the library, and read them to Rosie, and then we watch documentaries.

I had thought to make this school year just a standard survey course of “World History,” but Rosie was so fascinated with the pictures of the ancient history books that I doubt we’ll get farther than than the foundation of Rome before summer starts and the pool opens.

We started with pre-historic humans. We wondered at bone fragments that could be part of any creature and pieces of rock so rough that you have to take an archeologist’s word for it that these are actually hand axes, a great step forward in the development of tools.

On the Planet Charismatic, we generally grew up with the notion that it was a sin to believe in evolution, although the Church doesn’t teach that at all. I was raised with the general notion that belief in evolution was a liberal conspiracy that led, through means I couldn’t understand, to homosexuality and abortion. Good people interpreted Genesis literally.

Rosie has been learning about the Book of Genesis in the after school Bible club she attends once a week, so I didn’t know how my teaching her about prehistoric Man would mesh with what she was taught in her other lessons. I decided to make a stab at it anyway.

“Now, everything in the Book of Genesis is true,” I said, “But some of it is describing true things that are so big and so mysterious and ancient that there are no human words to describe them. Instead, we describe them with the language of stories, myths. As far as we can tell from science, God created human beings through a process called evolution, from a species of ape that changed gradually over the years and got smarter and more complex, until we ended up being human persons with a special kind of brain and a special kind of soul. That’s what Genesis means when it says God made Adam out of the earth.”

I wondered for a moment if this would crush her faith, but she just nodded and turned the page. Eight-year-olds can readily accept things that are too big and too ancient for them to understand. They still keenly realize that most of the world is, at that age. Grown-ups have often forgotten.

We read about neanderthals, and how they weren’t big boxy gorilla-like creatures with cartoonishly large jaws but would probably pass for homo sapiens sapiens, if you brought one to a modern city and dressed him in a trench coat. We talked about the ice age and the migration of early humans all over Europe and the Middle East, and further.

Climate change is another thing that we were supposed to believe was a myth invented by wicked people like Al Gore, for the purpose of promoting homosexuality and abortion. I don’t believe that anymore.

“Now, we know that man-made climate change is real,” I said, “And we have to do everything we can to mitigate that and help the environment. But climate change can also happen naturally, and in this time of history, the earth got much colder. That was called the ice age.”

This did not seem to destroy Rosie’s faith either. She nodded.

We looked at photos of neanderthals huddling in caves and hacking away at the carcasses of mammoths. Rosie drew a copy of this in her composition book. She carefully printed “THESE ARE NEANDERTHALZ. THEY ARE BUILDING A FIRE,” on the one-inch penmanship paper lines. I had to spell out most of the words verbally for her to write down. I counted that as her first history essay, and saved it for the portfolio.

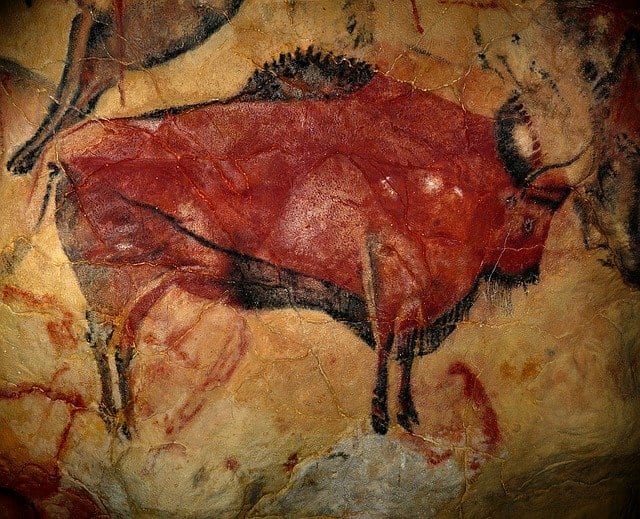

We looked at drawings of animal-skin tents built on bone frames. We admired photographs of cave paintings. We learned that the neanderthals, as far as anybody can tell, were the inventors of religion and of art.

“Most everyone has wondered about God and tried to talk to Him,” I said. “And God answers. God listens to everyone and I believe He speaks to everyone in one way or another. But I also believe God reveals Himself in special ways at certain times in history. We’re going to learn about some of those. As far as history can tell us, neanderthals were the first to have liturgies– to worship together as a group.”

Then it was time to study the first settlements, the invention of farming and domesticated animals. I showed her that old Bill Nye video on agriculture and the one on simple machines to help her understand the new technologies that the early humans had invented. We looked at more dioramas, of scantily clad people milking sheep and putting thatch on roofs. Rose pointed to a drawing of two women hitting the ground with implements.

“They’re pickaxing the new-growing seeds!” she cried.

“They’re tilling the soil,” I said, “before they plant the seeds.”

One of the pictures involved a small temple and an animal sacrifice.

This brought back a shudder and a flood of memories– this and that bad teacher, this and that terrible interpretation, all the lies I’d been told growing up, first in the Charismatic Renewal and then in Regnum Christi. Someone putting a stuffed dog I’d been sleeping with on top of the picture book I’ve been reading to demonstrate what an animal sacrifice would be like. Someone else saying it was about “giving the best you had to God,” meaning that the way to be a good Christian was not to find God in the things that you like best and use that love to help others, but to stay away from the things you liked best so you’d only be obsessing over your prayers all the time. Staring at the painting of the Sacrifice of Isaac in my Bible, and being told that “Abraham was willing to give the best thing that he had to God.” It was then that I realized that parents in the Charismatic Renewal view children as things that they have, rather than humans. I also realized, somewhere deep inside, that people who view children as things that they have and treat every impulse in their mind as a Word from the Lord were not trustworthy or safe, and I was terrified.

“It’s a form of prayer people used to do,” I told Rosie. “You take the farm animal you were going to kill to eat anyway, and instead of killing it on your farm, you kill it on an altar to show that all life comes from God. That’s all.”

And I turned the page quickly.

Someday, at home or at Bible Club, she’ll encounter the story of the Sacrifice of Isaac. I will interpret it for her in the way I’ve come to believe is true: that our father Abraham was a man who wanted to follow God and be good, but he didn’t have the first idea how. Left to his own devices he was sometimes terrible. But he always did what God asked him to do. So God called him up the mountain to prove a point. The point was that killing your children because you are a patriarch in charge of everyone and because you got a Word from the Lord, was not something that Abraham was allowed to do anymore. The new way God was showing him was something completely different.

I don’t know how to be a parent any more than Abraham knew how to be good, so I guess that’s something we have in common. But I’ve come to believe it begins with realizing that your children aren’t your property, and that you have to tell them the truth.

The next lesson was on ancient Sumeria.

We listened to a recording of a historian reading part of a recent translation of a hymn to Ishtar, written by a priestess thousands of years ago, the oldest extant poem in the world.

Rose didn’t recognize some of the words. “What’s a tryst?” she asked.

“A tryst?” I said. “Oh, that’s just kissing your boyfriend in secret where nobody can see.”

“Yuck,” said Rose. “What’s a boyfriend?”

But then it was suddenly time to move on to phonics.

No one said telling the truth to children would be easy. Though, usually, it’s easier than I thought.

(image via pixabay)

Steel Magnificat operates almost entirely on tips. To tip the author, visit our donate page.