In February, when the whole world appears dead, I think about the place where everything is alive.

I know I’ve written about this before, but bear with me. There’s so much more to tell.

I used to go to family reunions every year, down in the heart of West Virginia where my ancestors came from. Right now I live up in the chimney of Northern Appalachia, where it crashes into the Rust Belt. I can’t think of two places more different. Up here in the chimney, life is absolutely despised. Life is the diametric opposite to an idol known as “jobs,”which are given to people not from Northern Appalachia who drive up here in big trucks and then return where they came from before they have a chance to build any prosperity. For their sake and for the sake of wealthy investors, Northern Appalachia sacrifices mountaintops and forests, the blue of the sky, the visibility of stars, the physical health of its human inhabitants– even the futures of their children, if you believe in climate change. The folks around here tell me that climate change is a myth invented by liberals.

Pocahontas County isn’t like that.

Down there, they’ve found a way to make money off of tourists who want to admire nature, so they try to leave nature alone.

We used to go to family reunions every single year, and stay in the cabins in a state park in Pocahontas County. My “bad cousins” were there, the ones I’ve told you about, the boys who were nearly struck by lightning and then went to the beach with us. But we’d reached adolescence now, and they didn’t want to play with me. They wanted to tease me for being fat and then torture animals they’d found in the creek.

I didn’t like that, so I went for hikes by myself.

“Don’t ever go hiking by yourself,” said my aunts. “You’ll break a leg and die on the trail.”

But I went anyway.

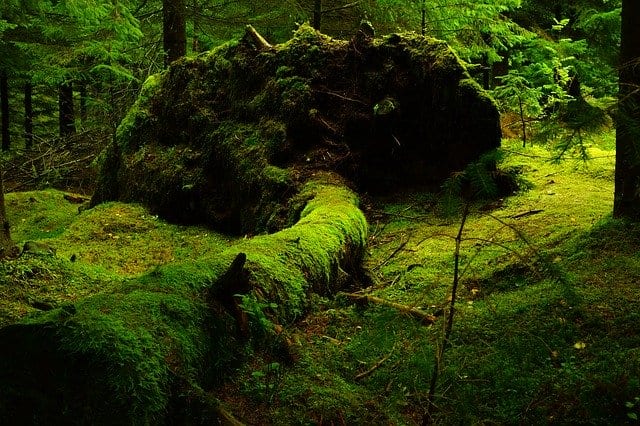

I went hiking alone on the trails in the state park, up in the deep woods where everything is alive.

Living out here in Northern Appalachia, I’ve nearly forgotten what that was like. I describe it for you now, almost not able to call it to mind, reciting the names of the things at which I used to marvel. Everything, everything, everything was alive. The loam beneath my feet crawled with grubs and insects. Harvestmen skittered over the tops of my shoes if I stopped to stand still for a moment. If I leaned on a tree trunk, ants would crawl over my hands. White-tailed deer, does and their yearlings, wandered so close to me I could almost reach out and pet them. Birds darted low across the path. This was all perfectly normal and natural, and yet I wondered at it like Alice in Wonderland finding out that the flowers in the garden could talk.

There was a time just before dark when the woods were more saturated with life than at any other time. That was my favorite time to go away by myself. The sun had almost set. The mountains to one side of me were awash in gold light, and the mountains to the other side were already in gloaming, and then I’d hear a sound like gunshots– beavers communicating, slapping the water with their tails. And then I would see the v-shape trailing across the lake, and then I would notice that the short bit of floating log near the shore was moving on its own volition, and then the log would dive under the water and I’d realize it was a live animal. I never saw beavers in the morning or at noon, only then. That was when the foxes came out; that was when the deer were especially bold, and I once glimpsed a black bear.

The noise increased at that time of evening, as well. The woods are never silent, but just before sunset they are cacophonous. The birds, the insects, the frogs all sang in chorus, and then night fell.

It really does fall, out there in the mountains, the way the blade of a guillotine falls. There aren’t any street lamps that come on after dark. One minute you’re in the bright-orange haze of sunset, and then it’s pitch black.

I didn’t always get back to the cabin before dark.

I suppose I was in real danger then– danger of breaking my leg, as my aunts had suggested, and then not dying but lying there on the trail all night until someone found me. There were rattlesnakes out there with venomous bites, and other snakes and rodents that could bite and do a lot of damage even without the venom. Black bears are harmless unless you startle one, and I couldn’t be careful not to startle a bear if I couldn’t see.

I was just about halfway down dirt path that would lead me home if I could follow it– it was built to go sharply uphill and then down to a bridge across the spillway of the artificial lake, winding around trees rather than having to cut any down. I could see the trail if I could see my feet, but my feet were in total darkness.

The fastest way home would be to stumble down the mountainside off the trail and swim across the lake– at the other side of the lake, there was a road that only went one way and would take me back to the cabins. But the mountainside was too steep to stumble downhill without tripping and smashing my brains out on a tree root or a rock.

The woods were noisy all around me, a chorus of insects and frogs.

I shuffled forward gingerly, arms out in front of me, for a few steps, and then I saw a diamond glowing in the darkness.

No, I wasn’t hallucinating– though I thought that I was at first.

A park ranger had bolted a rhombus shape made of white, reflective metal, to a tree. It did what my eyes couldn’t do and picked up the moonlight; it seemed bright as a city stoplight, in the absence of light pollution. I shuffled toward it.

There was another diamond on another tree, several feet beyond that, and I shuffled forward again.

Further away, another diamond had been painted in bright pink spray paint on a stump, and my eyes were adjusted to darkness now. I could see that perfectly. I could see nothing around it.

I followed metal and paint diamonds through the noisy dark, shuffling my feet, hands out in front like a mummy, until I came out of the woods on a slim wooden bridge with railing only on one side. I clung to the railing as I walked across the spillway, and then bolted through a meadow to the road.

And then I was back at the cabin, and no one had noticed I’d left.

This is the place I think about, up here where there is no life.

Sometimes I imagine what it would be like to see a hovering diamond in the dark, up here where I live now. If, one night, when I go for my walks through the smelly streets of LaBelle in Steubenville in Northern Appalachia, I happen to see a diamond suspended in the air in front of me, what would I do?

I would follow it like the Israelites following their pillar of cloud. I would follow it down every ugly street and across the poisoned Ohio River, deep into the woods until I got back to the place where everything is alive.

And this time I would not try to go home.

(image via Pixabay)

Steel Magnificat operates almost entirely on tips. To tip the author, visit our donate page.