I saw his Roman collar as he walked by– between the blue disposable face mask and the heavy down coat, a stripe of black with a square of white.

We were in the waiting room just outside the lab at the hospital, before dawn. I still don’t know why a lab that’s open until three in the afternoon only schedules its glucose tolerance tests at seven in the morning. You’d think the hospital of all places would understand that some people work nights. My struggles with insomnia mean I’ve usually done my writing staying up until three in the morning. I can’t just convince my body to go to bed at ten o’clock one night for a blood test. But there I was, after a nine hour fast, a single hour’s sleep, and a tense ride through a snow emergency with a friend who is luckily a morning person. And there was the cleric, a man about my age, who was presumably not getting a blood test because of a polycystic ovary syndrome diagnosis.

I mentioned yesterday that PCOS causes insulin resistance in the majority of its victims– in the fat patients like me and also in the lean patients, who are much rarer but do exist. It’s just one of the ways our hormones are out of balance. Today was my day to check if that was me. I fasted for eight hours and then turned myself in at seven for a fasting glucose blood test. I was now waiting for the result of that test; then they’d give me a glass of unappealing flat soda to give me a rush of blood glucose, then test my blood sugar at the one-hour mark, then again at the two-hour mark which would say whether I was diabetic, pre-diabetic or normal. Then I could go home.

The cleric sat down at a safe social distance from me, fiddling with his phone.

I stood up, pretending I wanted to pace around a bit. What I actually wanted to do was ask if he was a Catholic priest and if he could take me aside and hear my confession briefly. I could rattle off my sins very fast. I’ve been practicing the recitation for some time now, after all. The threat of COVID, Michael’s asthma, and my constant struggles with chronic illness meant I hadn’t been to confession since spring and had only been to Mass in person once. I haven’t been anywhere indoors for more than a few minutes since last March except our house, the grocery store and the hospital or doctor. I’ve been calling around trying to get a porch visit with the sacraments, but parishes are reluctant to do home visits due to the pandemic– understandably. When we get a car we’ll go to the parking lot Masses and confessions being held near Pittsburgh, but we don’t have a car now and there are no outdoor sacraments being offered in Steubenville at all. After a full minute, I got up the courage to walk up to the priest.

Just then, the phlebotomist called his name: not “Father So-and-So” but just his given name, and he went away.

When he came back out to get his coat and leave, I stood up again, but then the phlebotomist called my name, and it was too late.

I drank my flat soda.

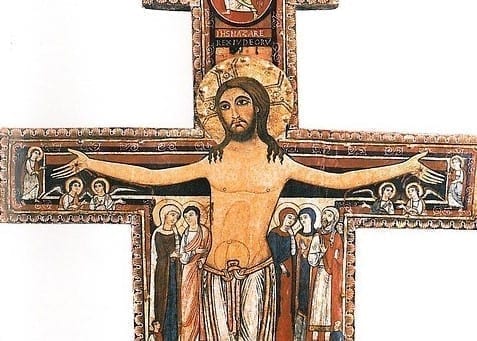

I came out and the priest was gone, but Christ was there. His image was on a San Damiano crucifix, under the wall clock and beside the television in the waiting area, behind where I’d been sititng. This is a Catholic hospital, originally affiliated with the Franciscan sisters, so Saint Francis and the San Damiano crucifix are ubiquitous in its decor. I used to have an aversion to all forms of Franciscan kitsch because of the abusive experiences I’ve had in Steubenville, but lately I don’t. Lately I see Saint Francis as a friend and ally against the injustice here, and I don’t mind the imagery anymore.

I gazed at Christ, and He gazed at me.

It wasn’t quite light out yet. Snow was still falling in wet clumps out the window, white cotton balls on a white cotton bed, completely silent. Inside was too quiet as well; so quiet I couldn’t ignore the irritatingly cheerful buzz from the morning show on the waiting room television. I’d been told not to leave the waiting room, but I asked the phlebotomist if I could wait in the hospital chapel just 2o feet away, and she said yes, as long as I came back in fifty-five minutes for the next blood draw.

The kiosk outside the chapel announced that there had been Mass there at 6:30 that morning, while I was being driven to the hospital through mounds of slush. It was probably still going on as I’d had my first blood draw– me giving one vial in an uncomfortable plastic chair and Christ pouring everything out on the cross for all time, me getting the wound tied off with hot pink tape and Christ getting shut away in the tabernacle after Holy Communion, twenty feet apart in the same building. I nearly cried at the thought that I’d missed it.

I went into the chapel, and Christ was there. They keep Him in an ugly tabernacle in a dark little side room with an ugly crucifix. First I went into the main chapel and read the Gospel for the day from the great big book, awkwardly– we all know women aren’t supposed to stand in that spot and read the Gospel. Then I hugged the statue of Saint Francis and held his outstretched, maimed hand. Then I went to the Eucharistic chapel and sat before the tabernacle.

I gazed at Him, and He gazed at me.

I begged Him that I would somehow not be diabetic on top of everything else– anxiety, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue and PCOS were enough. I reminded Him how diabetes was used as a threat in my house growing up, to try to encourage me to lose weight, when I had an undiagnosed genetic condition that made me inflate overnight like a mushroom and everyone treat me like a glutton. I would be humiliated to have diabetes. I reminded Him that I was desperate for another baby and taking all these measures to fix my health so I could ovulate again. I berated Him for letting me go this long, misunderstood, without a diagnosis.

I went into the “tranquility room” next to the Eucharistic chapel, where there is a comfortable chair and a container of gluten-free aromatherapy play clay. I played with clay in the Presence of the Blessed Sacrament until it was time for my next blood draw.

The phlebotomist read me my first glucose level, the fasting one, and it was normal, healthy, not even pre-diabetic. I was pleased. She pricked me a second time, right next to the first red spot. She took her vial of blood and tied off the wound with more pink tape. She ordered me back in fifty-five minutes.

I went to the chapel again, and Christ was there.

I complained again about the PCOS and reminded Him that I didn’t want to be diabetic. I sat there until I was about to fall asleep; then I retreated for the more comfortable seats in the waiting room.

I tried to read the book I brought. Oryx and Crake is a beautifully crafted dystopia novel, but I don’t recommend it if you’re already anxious and half asleep in a hospital waiting room during inclement weather. I can’t read with my glasses on and I can’t see at a distance with my glasses off, so I kept looking away from my book, squinting at the clock, and only seeing a white circle. Below the white circle was the San Damiano Crucifix. I couldn’t see Christ, just a blur of tacky colors, but He gazed at me.

I went back for my third blood draw. The phlebotomist took a third vial, leaving one last pinprick on the inside of my elbow: three dots in a little arc, a Trinity of tiny wounds. She wrapped my arm in pink tape one last time.

“What was my second glucose level an hour ago?” I asked casually.

She looked it up, and quoted me a number that was far too high, massively high, higher than the diabetics I know, a catastrophic number. She did not quote me the stern-looking red writing that was appearing on her computer screen around the doomsday number. I was too far away to see what it said. I thought about the one time I’d tested as barely pre-diabetic five years ago after a horrific eight-week menstrual cycle and the doctor had written it off as just an obese woman who needed self-discipline to lose weight. I’d tried to go on a diet but it hadn’t worked. Two years later another doctor had tested my blood and found it normal again so I’d thought the whole thing was just a mistake. What if someone had asked more questions? What if I’d had a diagnosis then, before it was so out of control? What if I’d somehow been more aggressive with trying to make someone believe me years ago when I was speechless at the doctor’s flippancy and too humiliated to seek more treatment? What was I going to do now?

I hadn’t been sick from the glucose drink when I drank it two hours previous, but I was just then.

“It’s high,” she said unnecessarily. “Under two hundred would be normal.”

“I, ah, guess I really am diabetic after all?” I said.

“There’s still one more test,” she said.

“I’ll look up the results in my patient portal when I get home.” I’ve had enough blood draws at this hospital to know that they always send you a link to your blood test results so you can play doctor and search Google for the results while you wait for the doctor to get back to you.

“Have a good day!” she said annoyingly brightly.

Fat chance of that.

I went to the store on the way home, so exhausted and worried that I forgot half the things on my list. I gobbled a keto-friendly sugar alcohol cookie and drank black coffee as I waited for the bus home, but they didn’t give me any energy.

At home, I logged into my patient portal. There was the low number for fasting glucose, then the gigantic number for the one-hour mark. And at the two-hour mark, the diagnostic mark, the one that matters most as far as I understand the rules of the test, my sugar was back down– not in the normal range but not near the diabetic range either. It was in the no-man’s land between, pre-diabetic but not at the point of no return. I’m not even sure if I’m diabetic or not at this point. Surely insulin resistant and I’ll have to take yet another medication, regardless.

Rosie had slept in; she was getting up so Michael could make her breakfast as I went to bed– too overwhelmed to be properly panicked, too hungry and thirsty to rest at first, too tired to get up and eat. The snow covered everything in a blanket of eerie silence.

And Christ was there as well.

Image via Pixabay

Mary Pezzulo is the author of Meditations on the Way of the Cross and Stumbling into Grace: How We Meet God in Tiny Works of Mercy.

Steel Magnificat operates almost entirely on tips. To tip the author, visit our donate page.