I am writing a narrative.

No, not that kind of narrative. Not the kind people actually want to read. I’m writing out my medical history. I tend to get tongue-tied and nervous at the doctor, and I have a long complicated history that’s hard even for me to remember. So I’m writing out every medical emergency I’ve had and every diagnosis I’ve been given in bullet points. It takes up six pages of type.

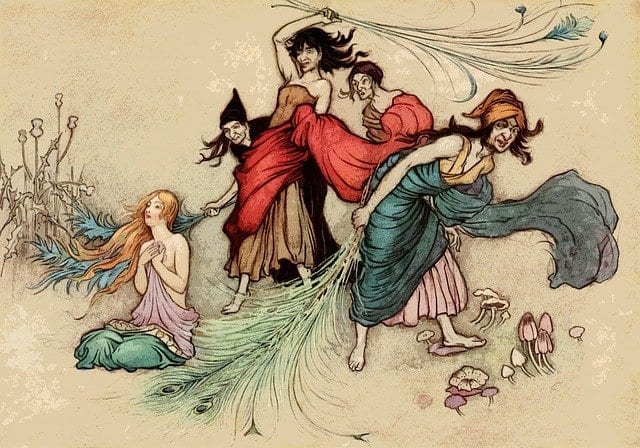

I went to school to learn to write the fun kind of narratives. My undergrad degree is in English with a creative writing concentration. I wanted a BFA in theater or studio art, but that ended up not happening, so I wrote stories about people more aesthetic than I was instead. I wanted to be a writer of fairy tales, like the ones I grew up reading. I loved to read about Narnia and Middle Earth. I was fascinated by the grisly Grimm’s Folktales with lavish and colorful illustrations. I loved the story of the Miller’s Daughter outsmarting Rumpelstiltskin, and Rapunzel with her impossibly long and thick hair.

I used to have thick hair, but I don’t anymore. It’s actually lucky thing that it got thin when it did, because that’s how I got my most recent diagnosis. I went to the doctor for something else and he noticed my scalp clearly visible. He asked if I was losing hair. He asked me to lift my mask for a moment so he could see the stubble on my chin. He noted the fact that Rose had never had a sibling, and started asking questions no doctor had ever bothered to ask before. Less than an hour later, I was diagnosed with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. As I understand it, all you need to qualify for that diagnosis is the irregular cycles and the clinical diagnosis of hyperandrogenism; the blood tests and glucose tests and ultrasounds I’m signed up for now will just help complete the picture.

Now I’m at home, reading medical journal articles with words I’ve never heard and can’t pronounce, words that sound like villains in a fairy tale. I’m trying to cope with yet another diagnosis. Chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, and now polycystic ovary syndrome. And I am typing up my medical history to show it to the doctor at our next visit, to help him figure out what to do next.

PCOS, I have learned, is an imbalance in the hormones in the body. It’s caused by genetics and by environmental factors. It causes the ovaries to not release an egg every month, which accounts for the infertility; it also can cause hirsutism and female pattern baldness, anxiety and acne, high blood sugar and high cholesterol. It makes you fat, and it makes it much more difficult to lose the weight once it’s piled on.

I’ve been living in this body for thirty-six years, and I finally understand a bit about what’s happening to it.

I am looking at my narrative, my six pages of bullet points of my medical history, and understanding a little more about what went wrong. The unbearable hormonal symptoms that made me think I was finally having another baby, only to be disappointed every time. The constant struggle with the anxious jitters. The weight gain that never went away no matter how many miles I jogged or what I ate. The pimply, puffy, squashy face that caused everyone from my mother and siblings to schoolyard bullies to random internet trolls to call me a pig. And now the hair loss.

It isn’t a vice after all, it’s a sickness.

Not that I won’t have to be extra careful, of course. I’m trying out a keto diet right now to help keep things from spinning further out of control. But it isn’t something I could make go away if only I were more virtuous. All bodies in a fallen world are imperfect, and my individual body is imperfect in this way. My genetics broke along these fault lines. This is my narrative.

I went through a spell of trying on head scarves and taking selfies a couple of years ago, because I like to cover my hair at church, so I started experimenting with different ways to tie the scarf on and look fashionable. A traditionalist Catholic troll kept downloading my profile pictures and sharing them with nasty captions about how ugly I am and how I must be lying about having survived a rape because nobody would touch me. Once he shared them to some kind of Men’s Rights Activists page. I got trolled by a hundred people over a weekend. This isn’t a happy memory, so I stopped covering my hair.

Now I’m wearing scarves again, this time to cover the bald spots rather than the hair, and it doesn’t feel good.

The books I read growing up were all about girls with long hair– that is, unless they ended up with it cut short for narrative reasons, like Anne of Green Gables after the episode with the green dye, or Jo March trying to buy a train ticket for her mother, or Rapunzel’s stepmother hacking off the braid to punish her for falling in love. I don’t remember any books about girls with bald spots. I don’t know how to be a woman with bald spots.

I don’t remember books about women who have to shave every day either, except of course the Weird Sisters from Shakespeare. Banquo tells the three witches that it’s hard to believe they’re women because of their beards.

It’s certainly hard for me to believe I’m a woman, right now.

I did used to want to be in Shakespeare plays. That was always the plan. I was going to be in a Shakespeare company and tour the country, but somehow or other I did this instead. This life and not the one I planned– this is my narrative.

Years ago I had a horrible traumatic episode where I didn’t get a period for fourteen weeks and also came down with acute gastritis at the same time. My stomach was swollen and I was nauseated. I thought Rosie was finally getting a sibling. And then I bled, heavily, and ended up in the emergency room, and there was no baby there, just my mysterious health symptoms no one would take seriously and an unattractive woman crying herself into dehydration. They gave me an IV of fluids and a set of mesh underwear, and sent me home.

A few weeks later I went to church. There was a beautiful family at Sunday Mass, the kind of stereotype you picture when asked to think of a Catholic family. There was a mother and father and seven happy children spaced neatly in age like stairsteps. The oldest was a religious sister in a brown habit, whom the family was visiting at Franciscan University. The youngest was a plump toddler in a pretty purple dress and bloomers. After Mass, the family asked the priest to take their family photo outside, and he did. He snapped photos while Rosie, who was four, climbed on the retaining wall with no fear for her own safety and I stood in catching distance. Rosie has always been a climber.

The family posed with their children in several adorable ways. Then they gathered around as the priest gave them a special blessing. He lauded them with a hundred compliments and thanked them for their “beautiful witness to life.” And then he went inside, straight past me without stopping.

He did not bless Rosie and me for our beautiful witness to life. He didn’t even look at us.

Everyone bears witness to life. Some people’s witness is photogenic, and mine is not. But everyone’s life is a witness.

Rosie is nine now. She has pimples and a scrubby brown Judi Dench haircut which she maintains herself by climbing on the sink to trim it. Rosie has absolutely no desire to be a beautiful woman from a storybook. She doesn’t like fairy tales; she likes Power Rangers and the Japanese shows they’re based on. She wants to be a naturalist and an author. She is fascinated by biomes and everything that is alive; she wants to tell the world that sharks are fascinating creatures to be admired rather than hunted down. Her greatest wish for the new year is for COVID-19 to be over so she can return to martial arts lessons and find a tumbling class that isn’t a girly one designed for aspiring cheerleaders. When we eventually move, she wants to stay in LaBelle so she can remain friends with the Baker Street Irregulars, but she wants it to be a house we own instead of rent so that she can have a dog and a rabbit and a chicken coop. I want those things for her, more than I can say. If I were a fairy tale character and could grant a wish, I’d grant that her life to be full of the good and righteous things she hungers for.

But even if she doesn’t, she will have a narrative. She will have a life story of the trials and challenges she’s fought to overcome. And that narrative will be a beautiful witness to life.

These six pages of bullet points are my witness that life is worth living. We can encounter joy, and find ways to be kind and receive kindness from others, even when everything goes so spectacularly wrong.

I am a witness to life, and this is my narrative.

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Mary Pezzulo is the author of Meditations on the Way of the Cross.

Steel Magnificat operates almost entirely on tips. To tip the author, visit our donate page.