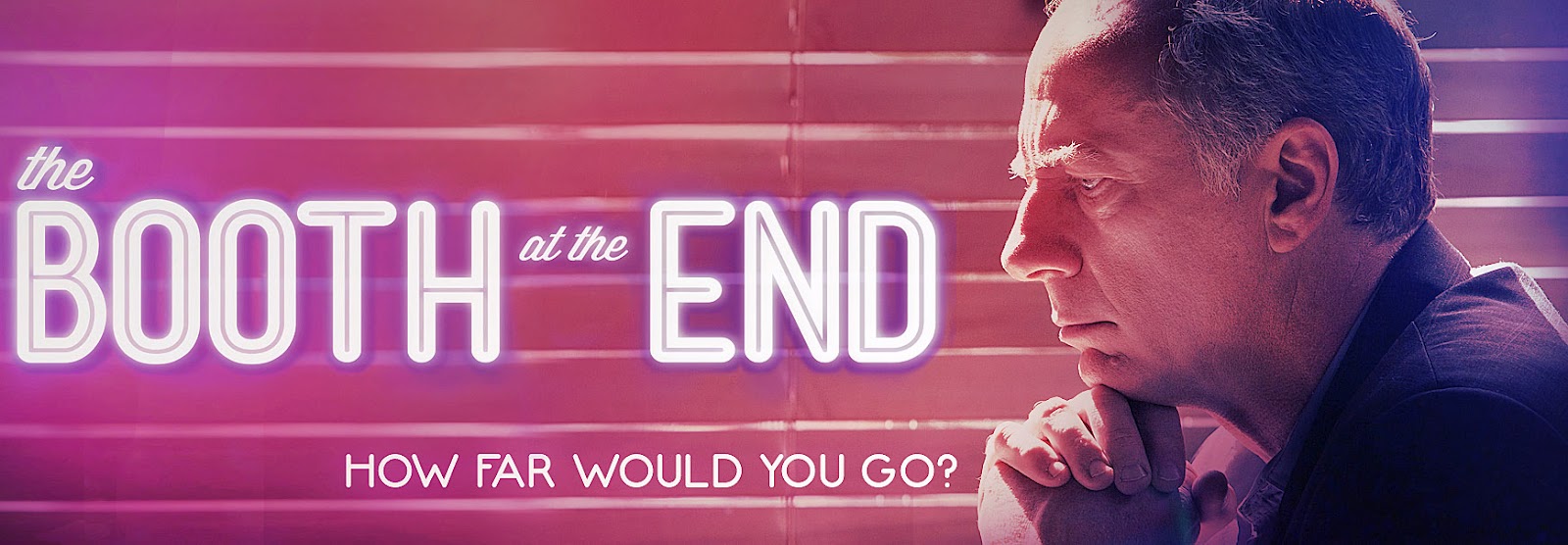

“I like strange things with strong, unique voices.” — The second part of my lengthy conversation with Christopher “C.K.” Kubasik, whose The Booth at the End show is one of my favorite “accidental discoveries” in recent memory.

Joseph Susanka: From Michael Eisner (who has produced both Booth seasons through his production companies, Tornante and Vuguru), to Xander Berkeley (perhaps the paradigm example of the “criminally underappreciated actor”) to directors Adam Arkin and Jessica Landaw, the cast and crew of Booth are folks with long, lauded careers in traditional cinema and television. What draws you all to such an unconventional opportunity as this one? And what is most exciting and most frustrating about “Broadband Content?”

Joseph Susanka: From Michael Eisner (who has produced both Booth seasons through his production companies, Tornante and Vuguru), to Xander Berkeley (perhaps the paradigm example of the “criminally underappreciated actor”) to directors Adam Arkin and Jessica Landaw, the cast and crew of Booth are folks with long, lauded careers in traditional cinema and television. What draws you all to such an unconventional opportunity as this one? And what is most exciting and most frustrating about “Broadband Content?”

Christopher “C.K.” Kubasik: I won’t speak for anyone else except to say that change is coming to Hollywood, most people recognize this, and some of those people are interested in exploring those changes purposefully.

Christopher “C.K.” Kubasik: I won’t speak for anyone else except to say that change is coming to Hollywood, most people recognize this, and some of those people are interested in exploring those changes purposefully.

As for me, I’m drawn to new forms of production and distribution for several reasons.

First, I want to get things made.

Many people outside of Hollywood assume you just show up, write something, and then the script is on its way into production. The truth is there are simply too many people all going for the same jobs. I’ve had several projects almost move forward in film and television, but nothing had gotten into production.

So, what do you do when the landscape is overstuffed with too few opportunities and too many people? You go to the frontier. A decade ago, cable television was the frontier.

Today, if you want to stand out, you go to the Internet.

* * *

The second significant appeal of Broadband, for me, is the absolute need to experiment and take creative risks.

Years ago FOX built its network on the backs of two strange shows—The Simpsons and The X-Files—that would have died in development at CBS, NBC or ABC. (Or, if they’d somehow gotten to air, would have been cancelled within weeks.)

When HBO wanted to make original content they made documentaries about subjects the networks (including FOX) would never touch. When it came to scripted content they aired OZ, a show about life inside a prison. And then they hit paydirt with The Sopranos and Sex in the City. HBO became a destination site for new entertainment because they were making shows other people would not have aired.

After that F/X put The Shield on television—a cop show that completely inverted what a cop show was “supposed” to be. They followed it with Nip/Tuck and Rescue Me. Whatever you think about these shows, they changed the game for F/X by creating shows that you couldn’t get anywhere else.

I loved these shows. I like strange things with strong, unique voices. Look at the books and movies and stories I’ve listed above. I’ll add more now:

Spielberg (Sugarland Express, Duel, E.T., Close Encounters of the Third Kind—all of them unique and strange, and certainly not the “no-brainers” they appear to be today). The novels of John Crowley, Gene Wolfe, and Michael Moorcock. The Homeric Epics. Beowulf. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Le Morte D’Arthur… all speak to me as utterly normal, but are out of step with the bulk of modern day storytelling.

* * *

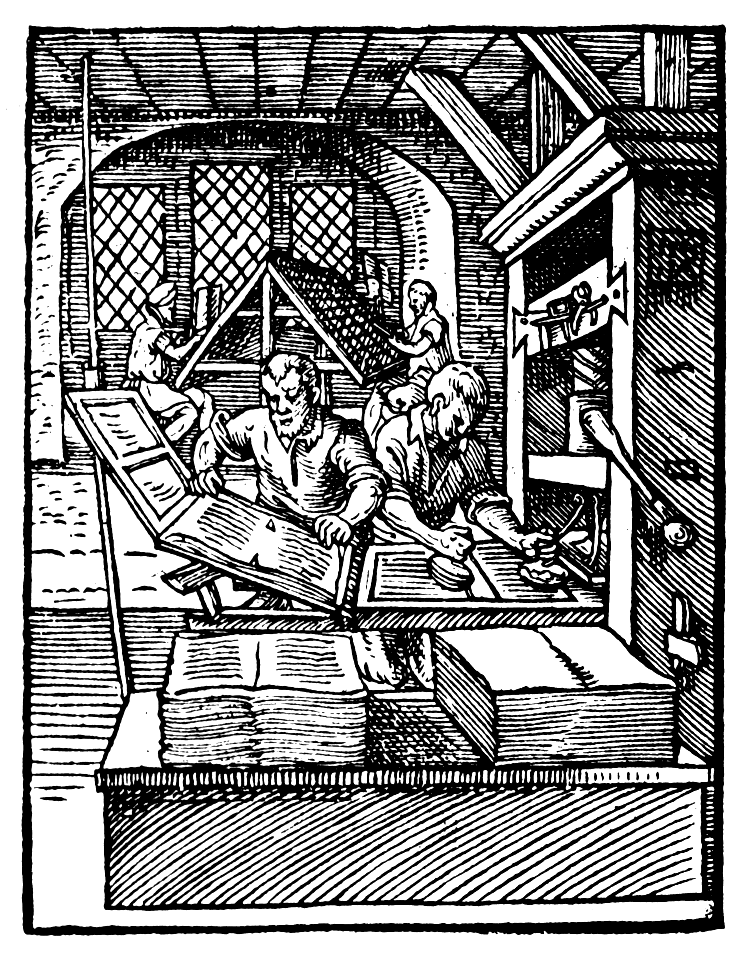

The third thing is that it is a new medium. As new as the printing press once was—or motion picture camera or television. People in Hollywood tend to see the Internet as a new means of distribution and only that. I don’t see it that way. I see it as its own new and unique medium.

The third thing is that it is a new medium. As new as the printing press once was—or motion picture camera or television. People in Hollywood tend to see the Internet as a new means of distribution and only that. I don’t see it that way. I see it as its own new and unique medium.

An example: Once upon at time there was no printing press. And then the printing press was invented. Now we can print things. Like what? Big books. The Bible is an obvious choice… but what else could one do with the contraption? People experiment. Storytelling moves from verse to prose since it is no longer a spoken form of storytelling. (Verse helped storytellers remember the tales. With the printing press, that is no longer a need). Pamphlet-sized chunks of longer stories are printed and sold in serialized form, which is how Charles Dickens’ novels are first printed and sold.

And, of course, novels. New tales in book form. But what is a novel? What is unique about it? Why is a big printed book different than a long tale told in verse?

Well, in a novel we begin exploring the interior life of the character in a way that plays and oral forms of storytelling of years past could not comfortably do. We are inside the interior thoughts of the character and those thoughts go into our thoughts. We’re not watching something happen, as in a play. We’re not hearing something happen, as when we listen to a storyteller. We’re thinking the tale in our own head as we conjure the words from ink into our mind. This is new. This is something the medium of the printed word can do that other media cannot.

Later, the motion picture camera is invented. What to do with it? Remember that in 1900 there was no common language of cinema, no multiplexes to guarantee income. It was all up in the air. The notion of a feature length film did not exist. All that we assume that is “normal” about movies had to be invented, in the same way that the printing press led to the novel — but without any obvious path to a thing called a novel.

Later, the motion picture camera is invented. What to do with it? Remember that in 1900 there was no common language of cinema, no multiplexes to guarantee income. It was all up in the air. The notion of a feature length film did not exist. All that we assume that is “normal” about movies had to be invented, in the same way that the printing press led to the novel — but without any obvious path to a thing called a novel.

So, the question becomes “What are movies for?”

Well, they are social: The economics of distribution (the rarity of projectors) dictate that you try to gather lots of people per showing and not make it a private experience. So, you want stories that work well for a communal experience. In this way they are like theater (which, also, depends economically on rounding up as many people per telling as possible). But unlike theater, which is primarily revealed through language, the cinematic experience is visual. So, you want something that is visually engaging and that engages people socially. Laughter, of course, is a terrific social experience. With this in mind, the success of silent comedies as the most successful use of the medium is no surprise.

* * *

Television, as a technology, creates new creative and economic opportunities. How do we encourage people to watch? We create half-hour and hour length programs that run on the clock so that people can make them part of their daily home life. (This is different than going to the movies, which is about leaving the routine of home life.) Thus, we get a tight structure of time for the storytelling because of the technology.

More importantly, I think, people had to ask, “What kinds of stories do people want to invite into their homes?” Because in the first decades of television there was only one television set per home. It was located in a room that the family used together. Thus, family friendly stories were paramount.

Television is different now, of course. Why? Because it’s not really television anymore. Cable, as a new technology, changed storytelling again. HBO introduced unedited, R-rated movies into the home. We began seeing stories in our homes that in years past we would not have let onto our televisions. As the technology changed, the kinds of stories changed. And so we have Breaking Bad or Mad Men and shows that would not have existed on television except in television’s early years (the Golden Age of Television) when people were still trying to figure out what to do with television and economic models hadn’t been solidified yet.

* * *

And now, Broadband storytelling. What is it? What kinds of story does it produce? Well, we don’t know yet. It’s all still being worked out. But here are some of my thoughts:

And now, Broadband storytelling. What is it? What kinds of story does it produce? Well, we don’t know yet. It’s all still being worked out. But here are some of my thoughts:

We don’t use it socially—certainly not as socially as when families gathered ’round the TV to watch The Waltons or The Brady Bunch.

In some ways it’s more like reading a book that watching television; we tend to do it by ourselves on a tablet or laptop or computer. If we do connect it to our televisions, we’re probably not doing it with the entire family but with friends, or one other person. It’s a much more intimate experience. Thus, in my view, we’re talking about a mix of cable programming and reading.

Moreover, the screens are smaller. In my view, competing with the cinematic experience—which involves the screen dominating us—doesn’t make much sense when we dominate the screens. Thus, we need explore what kinds of stories are strong on the smaller screen, rather than being smaller versions of the big screen.

Economically, the revenue stream isn’t there yet. So we need to keep cost down. Early television was dialogue-driven because taking pictures of actors’ faces and recording dialogue is cheaper than telling tale cinematically.

So, Broadband wants to steal lessons from 1950’s television, mix it with the private experience of reading a book, and combine it with storytelling that is more like going to the movies—or even better, storytelling that reaches before film and television.

What do we get with that? What new things will we be making as the medium expands? What new ways will be find to engage an audience? Like the novel or the half-hour sitcom or the feature length film (which all had to be created out of effort and experimentation), what have we not thought of yet? What new kinds of storytelling are coming down the road? I can’t wait to find out.

Part I can be found here. And Part III’s over here.

Attribution(s): Publicity images and film stills are the property of Hulu and other respective production studios and distributors, and are intended for editorial use only; images of Mr. Kubasik were provided by C.K. himself; “The Complete X-Files” is a product link, courtesy of Amazon; “Printer in 1568” by Jost Amman, licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons; “Vitascope Theater Buffalo Nov 1897” advertisement in the Buffalo Express, Sunday Morning, November 7, 1897, and licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons; “Matrix-ish” provided by Shutterstock.